The phrase, “the forgotten war” has been used by historians and other commentators in a number of contexts to describe a number of conflicts. In the particular case of Middleborough and Lakeville, however, it most certainly describes the Spanish-American War. The war fought between May and August, 1898, marked a turning point in American history when America emerged as a global power. However, despite this watershed aspect, little to no historical record has been left regarding local participation in or attitudes towards the war. Inexplicably Thomas Weston’s otherwise comprehensive History of the Town of Middleboro, Massachusetts published in 1906 contains no mention of the war, nor does it list the men who served at the time as it does for preceding conflicts. In the succeeding volume of the town’s history published in 1969, this deficit remained uncorrected - Mrs. Romaine speaks only to the failed attempt to found a Spanish War veterans' organization. Similarly, both Gladys Viger's History of the Town of Lakeville, Massachusetts (1952) and the more focused Salute to Those Who Serve (2002) do not list any Spanish-American War veterans for Lakeville. Surprisingly, the war is not even listed with the other conflicts in which Lakeville men were engaged. Nemasket's "Men of '98" were simply forgotten as was the conflict in which they fought.

The phrase, “the forgotten war” has been used by historians and other commentators in a number of contexts to describe a number of conflicts. In the particular case of Middleborough and Lakeville, however, it most certainly describes the Spanish-American War. The war fought between May and August, 1898, marked a turning point in American history when America emerged as a global power. However, despite this watershed aspect, little to no historical record has been left regarding local participation in or attitudes towards the war. Inexplicably Thomas Weston’s otherwise comprehensive History of the Town of Middleboro, Massachusetts published in 1906 contains no mention of the war, nor does it list the men who served at the time as it does for preceding conflicts. In the succeeding volume of the town’s history published in 1969, this deficit remained uncorrected - Mrs. Romaine speaks only to the failed attempt to found a Spanish War veterans' organization. Similarly, both Gladys Viger's History of the Town of Lakeville, Massachusetts (1952) and the more focused Salute to Those Who Serve (2002) do not list any Spanish-American War veterans for Lakeville. Surprisingly, the war is not even listed with the other conflicts in which Lakeville men were engaged. Nemasket's "Men of '98" were simply forgotten as was the conflict in which they fought.One reason for this oversight may be the dubious nature of the war’s origins and the fact that public opinion had clearly been manipulated by a war-hungry press at the time, clamoring to bring about a conflict with Spain. Yet this is no excuse for the neglect. Perhaps more of a factor is that the number of men who served in the war (about 300,000) remained small compared to earlier and later conflicts. In 1925, the Middleboro Gazette spoke to the small number of Spanish War veterans remarking:

If we consider the numbers killed in action, those who died of fever in southern camps and the numbers who have passed away during the last twenty-seven years, and subtract this from the total involved it does not leave a great many …. Consequently the Spanish War veterans make a poor showing as far as numbers go, at parades and on various occasions.

With too few veterans, the Spanish-American volunteers sadly were unable to record their own contribution or impress it upon the local consciousness as the G. A. R. had done for local Civil War veterans before them and other organizations would do for subsequent veterans. In the absence of such a group, Middleborough and Lakeville quickly forgot their boys.

The War’s Origins

The Spanish-American War was precipitated by the American interest in the struggle between Spain and colonial revolutionaries on the island of Cuba, and fueled by mounting press agitation on the part of the United States. Since the Ten Years War (1868-78), Cuban militants had sought unsuccessfully to separate themselves from Spain, with renewed actions in 1879-80, and again beginning in 1895. The brutal Spanish response to the rebellion attracted the unwelcome attention of the United States which saw its own interests jeopardized by the continuing instability on the island. Coupled with the desire to protect national interests, various parties within the United States also regarded the Cuban conflict of the mid-1890s as a means to expand American power and prestige, a goal fostered by the so-called “yellow press” of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer.

The Spanish-American War was precipitated by the American interest in the struggle between Spain and colonial revolutionaries on the island of Cuba, and fueled by mounting press agitation on the part of the United States. Since the Ten Years War (1868-78), Cuban militants had sought unsuccessfully to separate themselves from Spain, with renewed actions in 1879-80, and again beginning in 1895. The brutal Spanish response to the rebellion attracted the unwelcome attention of the United States which saw its own interests jeopardized by the continuing instability on the island. Coupled with the desire to protect national interests, various parties within the United States also regarded the Cuban conflict of the mid-1890s as a means to expand American power and prestige, a goal fostered by the so-called “yellow press” of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer.Middleborough’s focus would change, however, after the night of February 15, 1898, when the U. S. S. Maine which had been dispatched to Cuba at the close of January to protect American citizens and interests was destroyed in Havana harbor from a cause which still has not been definitely ascertained (though it remains doubtful that it was a deliberately aggressive action on the part of Spain). The explosion in Havana and the subsequent press campaign against Spain jolted Middleborough and Lakeville out of their quietude. While some residents concurred with President McKinley who counselled caution and stood opposed to war, others in Middleborough and Lakeville, as elsewhere, soon fell victim to the ensuing war fever which was stirred by much of the popular press. (To its credit, it appears that the Gazette took a much less sensational line).

War Fever

The possibility of war with Spain was a hotly debated topic throughout March and April in Middleborough and Lakeville. “The interest here in the war talk emanating from Washington has been intense the past week,” the Gazette reported in late March, 1898. Though several of the Civil War veterans in the local G. A. R. organization may have been presumed to know fully the horrors of war, they too came under the persuasive influence of anti-Spanish sentiment that spring. “Many of the old G. A. R. veterans have felt the old battle spirit firing their blood and the young men stand ready to assist their country when the emergency shall arise.” At the Middleborough post office in the Thatcher Block on Center Street, “an intimation of Spanish strife [was] noted” in the form of a Navy recruiting poster which was on prominent display. A month later, war fever remained “very intense in this vicinity”, prompting one resident “to give free rein to his feelings [and] cut the heads off all his black Spanish fowl.”

The possibility of war with Spain was a hotly debated topic throughout March and April in Middleborough and Lakeville. “The interest here in the war talk emanating from Washington has been intense the past week,” the Gazette reported in late March, 1898. Though several of the Civil War veterans in the local G. A. R. organization may have been presumed to know fully the horrors of war, they too came under the persuasive influence of anti-Spanish sentiment that spring. “Many of the old G. A. R. veterans have felt the old battle spirit firing their blood and the young men stand ready to assist their country when the emergency shall arise.” At the Middleborough post office in the Thatcher Block on Center Street, “an intimation of Spanish strife [was] noted” in the form of a Navy recruiting poster which was on prominent display. A month later, war fever remained “very intense in this vicinity”, prompting one resident “to give free rein to his feelings [and] cut the heads off all his black Spanish fowl.”As calls that the nation proceed with caution increasingly were stifled, the Middleboro Gazette found itself joining the growing bandwagon and took pains to indicate that the patriotism of the community was unquestioned. “In the present condition of war like plans and preparations, it might be opportune to say that Middleboro has a military history, seldom surpassed by towns of her size …. Doubtless should the emergency arise the old town will not be backward in once more giving her sons to the defense of national honor.”

April was a month marked by much uncertainty locally, though preparations were hastily being made nationally to put the country on a war footing. At the start of April, the standing army consisted of 2,143 officers and 26,040 enlisted men, and efforts were undertaken to rapidly expand this through the recruitment of volunteers. To Massachusetts was to be delgated the task of defending its own coast, and locally George Fred Williams began organizing a regiment (though with no apparent success).

On April 25, 1898, in response to an ultimatum from the United States that it withdraw its forces from Cuba, Spain declared war. At home, the only immediate perceptible change was seen in a rise in consumer prices. As early as late April, 1898, “Middleboro has already begun to feel the effects of the war in the prices of provisions”, the price of a barrel of flour jumping in price an additional 75 cents to a dollar. Nonetheless, things (including prices) quickly returned to normal, and flour returned to its pre-war price by the start of June.

Soldiers & Sailors

While a number of men enlisted immediately following the declaration, Middleborough’s recruiting efforts were not formalized until mid-June, 1898, when Lieutenant A. E. Lewis and Sergeant Henry Rickard of Company D, Fifth Regiment, opened a recruiting office in the Darrow Block on South Main Street. “Inside of two minutes after the office was opened, Edward J. Shay, James Murphy and Michael J. Cronan had signed the enlistment roll [and] … during the day 22 signatures were obtained.” While not all of the men that enlisted that day passsed the later physical examination, ten did, and they would become the first Middleborough and Lakeville men formally sent to war. Men enlisting in Company D were to be paid $22.60 per month, the federal government paying $15.60 of that and Massachusetts the remainder.

While a number of men enlisted immediately following the declaration, Middleborough’s recruiting efforts were not formalized until mid-June, 1898, when Lieutenant A. E. Lewis and Sergeant Henry Rickard of Company D, Fifth Regiment, opened a recruiting office in the Darrow Block on South Main Street. “Inside of two minutes after the office was opened, Edward J. Shay, James Murphy and Michael J. Cronan had signed the enlistment roll [and] … during the day 22 signatures were obtained.” While not all of the men that enlisted that day passsed the later physical examination, ten did, and they would become the first Middleborough and Lakeville men formally sent to war. Men enlisting in Company D were to be paid $22.60 per month, the federal government paying $15.60 of that and Massachusetts the remainder.There were a variety of reasons which attracted Middleborough and Lakeville men to enlist, as pointed out at the time.

The make-up and motives actuating the regiments were essentially the same. Men from every walk in life filled the ranks, - the lawyer, the mechanic, the laboring-man, the college student, marching shoulder to shoulder. One of the stock questions asked one another was, “What induced you to enlist?” The answers were as various as they were evasive, ranging all the way from the man who had dined “too well, but not wisely” and who had enlisted immediately after dinner, to the man whose avowed principal motive was patriotism. And if sympathy with the famous remark, “Our country! In her intercourse with foreign nations may she always be in the right; but our country, right or wrong!” can be called enlisting from patriotism, then the great majority of the men must have that credit, for it was for their country they enlisted.

Middleborough’s first quota of young men entered service at the end of June, and appropriate departure exercises were held to see off the men. A supper in the G. A. R. hall in the former Peirce Academy building was “followed by a short session of speechmaking. The volunteers were escorted to the station, and the procession included the police and fire police, Middleboro Band, E. W. Peirce Post 8, G. A. R., T. B. Griffith Camp S. of V., delegations of firemen and lastly the ten recruits.” These new soldiers who were to be mustered into Company D, known as the “Standish Guards”, Fifth Regiment, “were dressed in campaign hats and butternut brown drilling, which will be the service uniform. All were armed with the new model rifle such as the regular army carries.”

In early July, additional recruits were requested, the call coming to Middleborough by telephone, surely one of the first such messages in the town’s history. The call by Captain W. C. Butler of Company D, Fifth Regiment, was responded to by a recruitment rally presided over by Judge George D. Alden. Speakers included Reverend M. F. Johnson, Councillor N. F. Ryder, Reverend William Bayard Hale of the Church of Our Saviour, Charles A. Howes of the G. A. R., Dennis D. Sullivan and Corporal A. J. Caswell of the Fifth Regiment. An additional number of Middleborough men joined the “Dandy Fifth” as a result of this rally.

Though most Middleborough men, like those in the Fifth Regiment, did not see combat, some did. “John Smith … was in the thickest of the fight with the 7th U. S. Infantry at Santiago. One of the men fighting at his side was mortally wounded but he escaped uninjured in his first engagement.”

In mid-July, Chester A. Hopkins was rumored to have died of wounds received at Santiago. “A letter was received from him by George W. Starbuck stating that he had been wounded in the hand slightly and that he was then in the marine barracks at Key West.”

Despite these fortunate escapes, the tragedy of the war was brought home to Middleborough residents with the death of Captain John Drum, the father of A. L. Drum who served as the manager of the Middleboro Municipal Light Plant. Captain Drum of the 19th infantry was killed in action at Santiago, Cuba.

The War Ends

Fortunately, the war in Cuba was to be brief. News of the surrender of Santiago on July 17 was received in Middleborough “with much delight. The church bells were rung, whistles blown, salutes fired and other demonstrations made over the surrender of the first European general and army to the Yankees since the days of Cornwallis.” The war, itself, in Cuba ended the following month, on August 12, when an agreement preparatory to a final peace treaty was signed by American and Spanish representatives. The town’s reaction appeared to be less subdued on this occasion. “No public demonstration was held but the news was received with lively satisfaction.”

Fortunately, the war in Cuba was to be brief. News of the surrender of Santiago on July 17 was received in Middleborough “with much delight. The church bells were rung, whistles blown, salutes fired and other demonstrations made over the surrender of the first European general and army to the Yankees since the days of Cornwallis.” The war, itself, in Cuba ended the following month, on August 12, when an agreement preparatory to a final peace treaty was signed by American and Spanish representatives. The town’s reaction appeared to be less subdued on this occasion. “No public demonstration was held but the news was received with lively satisfaction.”Nonetheless, troops would still be required for the occupation of Cuba and Puerto Rico. In August, 1898, Joseph H. Edwards, then serving with the First New Hampshire Regiment, was to be sent to Puerto Rico, and the Gazette noted of the Fifth Regiment that “there are chances that the regiment may be sent to replace some of the troops withdrawn from Porto Rico and Cuba.” By late August, it had been announced that the regiment would in fact be kept in service at Camp Dalton in Framingham. In September, it was relocated to Camp Meade in Middletown, Pennsylvania, at which time it was declared by the Old Colony Memorial as “one of the finest military organizations ever raised in the Old Bay State.” In November, Company D was transferred from Fort Meade to Greenville, South Carolina, where it would remain for the duration of its enlistment and where it found a warm welcome from Mayor Williams of that city. The Fifth Regiment, in fact, named its encampment Camp Williams after the mayor who saw in the Massachusetts soldiers an opportunity for further reconciliation between north and south.

When I learned that a Massachusetts regiment was coming to South Carolina, I felt that the two states who did the most fighting and stirring up of leaders in the days of the rebellion, ought to join hands across the years that have intervened for a reunited country – the best in the world. When your regiment marched down by city hall I could not help crying for joy, because of the opportunity as an ex-confederate soldier to welcome Massachusetts soldiers to our city and state as my brothers.

Soldiers at the camp took on various responsibilities including Michael J. Cronan who in January, 1899, was appointed prison guard. Camp life was relieved by letters and packages from home. In late July, 1898, employees of Leonard, Shaw & Dean, shoe manufacturers on Peirce and Oak Streets, sent Middleborough members of Company D a boxful of food. Such boxes were extremely welcome, the quality and quantity of army food sometimes being less than desirable. In September, 1898, Ernest C. Hannon wrote home to Middleborough regarding the transfer of Company D to Fort Meade, Pennsylvania, when “they ran short of provisions and went from 11 o’clock in the morning until 5 the following morning with but three pieces of hardtack to eat.”

Throughout the winter in Greenville, rumors continued to circulate that the Fifth Regiment was due to be shipped to Cuba, to take up duties in Havana. One report even stated that the unit would ship out from South Carolina in January. Such was not to be the case and in March, 1899, Company D was mustered out, with Middleborough’s soldiers returning home during the first week of April.

The Home Front

In a war marked by excessive jingoism, it is not surprising that patriotic displays were rampant. Workers at the Leonard & Barrows shoe manufactory at the corner of Center and Pearl Streets purchased a large American flag measuring 31 by 12 feet and in early June sponsored a flag raising, the flag being hung across Center Street.

Still yet another flag raising was performed at the Middleboro-ugh railroad station in late June, attended by some 2,500 people. The flag, purchased by employees of the railroad was unfurled from an 80 foot pole, the ceremony chaired by 86 year old Colonel Earl E. Rider of Middleborough who had long been associated with the railroad.

Still yet another flag raising was performed at the Middleboro-ugh railroad station in late June, attended by some 2,500 people. The flag, purchased by employees of the railroad was unfurled from an 80 foot pole, the ceremony chaired by 86 year old Colonel Earl E. Rider of Middleborough who had long been associated with the railroad.While local social and civic organizations, as well as businesses, supported the war effort, so too did the town’s churches. While many denominations prior to the war had been opposed to any hostilities towards Spain, once war was declared local churches became prominent supporters of the war effort. “A practical evidence of the interest felt by the church militant in the success of the present struggle is noted by the display of a magnificent banner at the Central Congregational church. This was procured by pastor Woodbridge and flung high on the tower Wednesday.” Reverend Hale of the Church of Our Saviour took a prominent role in the recruitment rally in mid-summer 1898, while Reverend Frederic C. Brown of the First Unitarian Church took a more active role. He resigned the pastorate which he had held since October, 1896, to enlist as a chaplain in the U. S. Navy.

Memorial Day, particularly, became the vehicle through which the town was able to vent its patriotic ardor.

Memorial day was never more generally observed in this town than on Monday last. The day possessed an unusual significance, in that it was the first observance of Memorial day while the country was at war and the patriotic feeling generally prevailing was increased by the profuse display of flags, almost everyone wearing something indicative of the national colors. The members of the G. A. R. and allied organizations turned out with full ranks, 130 strong. Hon. Hosea M. Knowlton, attorney general of the commonwealth gave the address in Town hall in the evening.

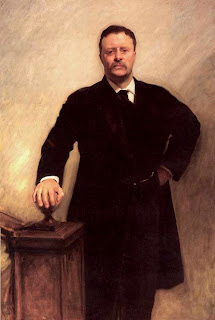

During this period, Middleborough frequently stressed its unique connection to the war through General Leonard Wood who at one time had been a pupil at Peirce Academy in Middleborough. The Gazette on a number of occasions reminded its readers of the association between Wood, one of the founders and the commander of the famous "Rough Riders", with the town.

Economically, the war did some to boost business conditions and certain local firms benefited from the war. Keith & Pratt at North Middleborough secured a government contract and was reported as “rushing … out in short order” a consignment of 700 pair of Army shoes in early June. To finance the war, new taxes were established, leading many townspeople to complain. The Gazette maintained that the taxes, in reality, were less onerous than depicted. “The war tax, it is true, affects checks, telegrams, express packages, money orders, and many of the gastronomic luxuries, but it does not apply to dog licenses nor marriage certificates. Cheer up!” Nonetheless, the war tax was carefully monitored and followed. In July, 1898, the local paper reported the first affixation of a war revenue stamp “to a probate county bond for this county … by Nathan Washburn, Esq.” Yet despite these taxes, residents remained generous in funding the war effort, subscribing $20,000 towards war bonds.

Homecoming

Company D was mustered out at Greenville, South Carolina, in late March, 1898, and immediately returned home. On their way homeward, Fred A. Thomas, Michael J. Cronan and Nelson Frank broke the journey with a stop at Washington where they “left the cars in search of a restaurant, entering the first they came to. It was a high priced establishment but two United States senators came to the men and invited them to order whatever they wanted. The senators paid all the bills.” It was a fine acknowledgement of the men's service.

Throughout the war, the older veterans of the G. A. R. had taken a paternal concern for the Spanish American volunteers, and it was to them that the task or organizing a celebration for the returning soldiers fell. “The Grand Army men all hold the volunteers for the Spanish war in high regard, for the old soldiers know how to appreciate as none others can, the sacrifices and hardships of the men of ’98.”

The Fifth Regiment arrived at Boston on April 3, 1899. Upon the arrival of the Middleborough contingent of Company D in town, members of the E. W. Peirce Post No. 8, G. A. R., and T. W. Griffith Camp, Sons of Veterans, headed by the Middleboro Band marched to the depot. The men were escorted back to the G. A. R. Hall where noted town officials addressed the audience and a poem written especially for the occasion was read by Adoniram J. Raymond.

Not all Middleborough and Lakeville's men would return at this time, however. A number including Justin Hayward, Christopher Reed and Frederick White saw service in an action since known in America as the Philippine Insurrection. Conditions on the islands were brutal, moreso than on either Cuba or Puerto Rico during the late war. White wrote the Gazette "that a soldier's life is very hard and trying in that country, especially during the rainy season." White reported that "more than 100 have deserted from his regiment, and that many more are dead and dying from the effects of the climate and food."

Veterans’ Organizations

Following the war, much hope was placed in the formation of a Spanish-American War veterans’ organization. Plymouth members of Company D were told: “Have pride in what you have done, you were ready – the opportunity was wanting. You are veterans of the Spanish war, and when the veteran association is formed, as it will be soon, hold it as dear as do the men of the Grand Army.” It was believed that such a group would not only aid former soldiers in the war, as well as their families, but would also help perpetuate their memory and their contributions. Such, however, was not to be the case.

Following the war, much hope was placed in the formation of a Spanish-American War veterans’ organization. Plymouth members of Company D were told: “Have pride in what you have done, you were ready – the opportunity was wanting. You are veterans of the Spanish war, and when the veteran association is formed, as it will be soon, hold it as dear as do the men of the Grand Army.” It was believed that such a group would not only aid former soldiers in the war, as well as their families, but would also help perpetuate their memory and their contributions. Such, however, was not to be the case.During the war, Middleborough had raised funds to help support the volunteer soldiers and their families. In mid-July, 1898, a mass meeting was held in Middleborough Town Hall with addresses by W. B. Stetson, Nathaniel F. Ryder, Matthew H. Cushing, Reverend M. F. Johnson, Judge George D. Alden and John E. Gilman, past senior vice-commander of the Massachusetts G. A. R. Over $180 was raised, and the expectation was that an additional $120 would be forthcoming. A month later, in August, the Board of Selectmen administered its first case of Spanish-American War aid when it allowed aid to the wife of one Middleborough resident serving with Company D.

Yet while the financial needs of the Spanish War veterans were addressed, the failure to found a local veterans’ group locally meant that many of their other needs went unattended. The need for a Spanish-American War veterans’ organization was brought home clearly in March, 1925, with the death of Victor Gabrey, a brother of Louis Gabrey of Nemasket Street, Middleborough. Victor Gabrey had served in the war with the 26th Company of Infantry, 20th Brigade, M. V. M., from Cambridge. In the absence of a Spanish War veterans group, the local Simeon L. Nickerson Post, No. 64, American Legion, took charge of Gabrey’s funeral and his burial in St. Mary’s Cemetery. “It is a fact significant of the spirit of the Legion that every member asked to act as escort on this occasion did so willingly, putting aside his own work, glad to perform a service for one who had borne arms in defense of the United States, although he was a stranger to them and not a member of the Legion.”

Though efforts had been made in 1914 by Michael J. Cronan and Joseph P. Hyman to found a veterans’ group, they were without success. Possibly prompted by the attention called to the lack of such an organization by the Gabrey funeral, the Southeastern Council of the United States Spanish War Veterans attempted in September, 1925, to organize a camp in Middleborough, then the largest community in southeastern Massachusetts without such an organization. The Gazette itself seemed perplexed by the failure of the community to found such a group. “There seems to have been a lack in the spirit of the Spanish War veterans about here in organizing a camp which is singular in view of the fact that the Spanish War veterans were 100 per cent volunteers.” While the proposed organization sought to take in members having served between April, 1898, and summer, 1902, in the Spanish American War, Philippine Insurrection and China Relief Expedition [Boxer Rebellion], there appears to have been little success and Middleborough seems to have remained with a specific group either to advocate or to care for the town’s Spanish War veterans.

Middleboro Gazette, "What the Gazette Was Saying Twenty Five Years Ago", January 19, 1923:7; ibid., January 26, 1923:6; ibid., February 2, 1923:6; ibid., February 16, 1923:6; ibid., February 23, 1923:6; ibid., March 30, 1923:5; ibid., April 6, 1923:5; ibid., April 20, 1923:9; ibid., April 27, 1923:5, ibid., May 4, 1923:10' ibid., May 11, 1923:6; ibid., May 18, 1923:10; ibid., June 1, 1923:6; ibid., June 8, 1923:9; ibid., June 22, 1923:9; ibid., June 29, 1923:9; ibid., July 6, 1923:6; ibid., July 13, 1923:5; ibid., July 20, 1923:6; ibid., July 27, 1923:6; ibid., August 3, 1923:6; ibid., August 17, 1923:10; ibid., August 31, 1923:5; ibid., September 21, 1923:6; ibid., November 16, 1923:6; ibid., January 18, 1924:7; ibid., January 25, 1924:6; ibid., February 22, 1924:6; ibid., March 28, 1924:6' ibid., April 4, 1924:6; ibid., April 11, 1924:6; ibid., January 30, 1925:8; ibid., March 20, 1925:1; "Spanish War Veteran Given Military Funeral", March 20, 1925:1; "What the Gazette Was Saying Twenty Five Years Ago", May 1, 1925:8; "To Organize Camp Here", September 4, 1925:6; "Steps to Institute Camp", September 11, 1925:1; "What the Gazette Was Saying Twenty Five Years Ago", March 12, 1926:6; "Old Middleborough", July 17, 1931:1.

Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1798-1892 (National Archives Microfilm Publication T1118, 123 rolls); Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Old Colony Memorial, “Standish Guards’ Departure”, July 2, 1898:4; "County and Elsewhere", July 30, 1898:1; September 10, 1898:1; “Ordered to Cuba”, Nov. 26, 1898:4; “Fifth Will Stay”, Dec. 3, 1898:5; “The Guards Coming Home”, March 11, 1899: 1.

United States Federal Census Records, Middleborough, MA

U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1893-1940 (National Archives Microfilm Publication T977, 460 rolls); Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938 (on-line database). Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007. Original data: Historical Register of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1749, 282 rolls); Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

For further information on the Spanish-American War visit:

+of+Smoky+Mountains+018.jpg)