The following item is posted in response to a query I had regarding President William Howard Taft's 1912 visit to Middleborough. The article was originally published in the Middleboro Gazette and republished in the Middleborough Antiquarian in May, 1989.

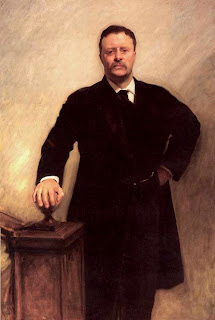

Though progressive Republicanism was never as influential along the East Coast as it was in the West and Midwest, it did create an enormous pull on sympathies of Middleborough voters. At the start of this century, as many of the state's urban voters began taking to the Democratic Party, many rural communities in southeastern Massachusetts, including Middleborough, began developing a progressive Republican bent. The high water mark of progressive Republicanism in Middleborough was the brief period of 1912-13. During that time, the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party, under the aegis of Theodore Roosevelt, exerted a tremendous impact upon the political life of both the town and the nation. The 1912 presidential campaign brought both Roosevelt and President William Howard Taft to Middleborough in a clash of progressive and conservative Republicanism. The 1914 elections, however, sounded the death knell for Bull Moose Progressivism in Middleborough as previously disaffected progressive Republicans returned to the fold of a liberalizing Republican Party or joined the ranks of the burgeoning Democratic Party.

Though progressive Republicanism was never as influential along the East Coast as it was in the West and Midwest, it did create an enormous pull on sympathies of Middleborough voters. At the start of this century, as many of the state's urban voters began taking to the Democratic Party, many rural communities in southeastern Massachusetts, including Middleborough, began developing a progressive Republican bent. The high water mark of progressive Republicanism in Middleborough was the brief period of 1912-13. During that time, the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party, under the aegis of Theodore Roosevelt, exerted a tremendous impact upon the political life of both the town and the nation. The 1912 presidential campaign brought both Roosevelt and President William Howard Taft to Middleborough in a clash of progressive and conservative Republicanism. The 1914 elections, however, sounded the death knell for Bull Moose Progressivism in Middleborough as previously disaffected progressive Republicans returned to the fold of a liberalizing Republican Party or joined the ranks of the burgeoning Democratic Party.Bull Moose Progressivism, itself, was an indirect consequence of a political maneuver made by Roosevelt. Following election to the White House in his own right in November, 1904,the progressive Roosevelt renounced a third term for himself as president in the "bully pulpit," though this did not prevent him from personally hand-picking his successor - Secretary of War William Howard Taft. Despite a year-long African safari with his son Kermit followed by a triumphal European tour, Roosevelt could not arrest the presidential itch and by February, 1912, considering Taft disloyal to the cause of progressive Republicanism, Roosevelt declared, "My hat is in the ring" for a third presidential term.

Vying with Roosevelt for the Republican bid were progressive Wisconsin Senator Robert "Battle Bob" La Follette, who sought to deprive Roosevelt of the mantle of progressive Republicanism, and President Taft, candidate of the conservative or "stand pat" Republicans. La Follette virtually disqualified himself at the beginning of February with a rambling and incoherent speech, a consequence of overwork, while Taft had his own drawbacks. Taft's tendency to fall asleep in public (once, as a front row mourner, he drifted off at a funeral to the utter horror of his military aide, Archie Butt), his obvious corpulence, his heavy reliance upon arch-conservative Speaker of the House "Uncle Joe" Cannon of Massachusetts and his responsibility for the loss of the House Republican majority in the 1910 election were all detriments to the Taft campaign. Nor did it help that the president self-deprecatingly referred to himself as both a "cornered rat" and a "straw man" in the campaign.

Vying with Roosevelt for the Republican bid were progressive Wisconsin Senator Robert "Battle Bob" La Follette, who sought to deprive Roosevelt of the mantle of progressive Republicanism, and President Taft, candidate of the conservative or "stand pat" Republicans. La Follette virtually disqualified himself at the beginning of February with a rambling and incoherent speech, a consequence of overwork, while Taft had his own drawbacks. Taft's tendency to fall asleep in public (once, as a front row mourner, he drifted off at a funeral to the utter horror of his military aide, Archie Butt), his obvious corpulence, his heavy reliance upon arch-conservative Speaker of the House "Uncle Joe" Cannon of Massachusetts and his responsibility for the loss of the House Republican majority in the 1910 election were all detriments to the Taft campaign. Nor did it help that the president self-deprecatingly referred to himself as both a "cornered rat" and a "straw man" in the campaign.In contrast, the dynamic T. R was enormously popular with the rank and file Republican voters and he hoped to win numerous delegates in the 13 presidential primaries, 1912 being the maiden year of the primary system. The Massachusetts primary was scheduled for Tuesday, April 30, and both Roosevelt and Taft spent much time in the commonwealth posturing for the event.

On Friday evening, April 26, President Taft gave a major address in Boston which left him physically and emotionally exhausted. Taft told the Boston audience, "I do not want to fight Theodore Roosevelt, but sometimes a man in a corner fights. I am going to fight." At Boston, Taft raised the third term issue, concerned that Colonel Roosevelt "should not have as many terms as his natural life will permit." Ironically, it was just this issue which was responsible for a foiled assassination attempt of Roosevelt by a disgruntled New York bartender in October in Milwaukee.

Roosevelt was the first of the two contenders to speak in Middleborough, arriving April 27 , three days before the primary. Roosevelt's stop in Middleborough was part of his second trip to New England since the beginning of April. Interrupting the New England tour was a side journey to Kansas and Nebraska which nearly cost T. R's voice, so strenuous were the speaking engagements. Because of the strain of the tour, Roosevelt knew it would be futile to mount a full-scale railroad car campaign when he returned to New England at the end of April. "It is folly to try to make me continue a car-tail campaign," he said. Consequently, Roosevelt scheduled appearances only at Fall River, New Bedford and Boston for the morning and evening of the 27th. Due to the efforts of the local Roosevelt Club, however, the itinerary was altered to include brief stops in Brockton, Middleborough and Taunton.

Arriving from Brockton one hour before the scheduled arrival time of 12:30, Roosevelt's motorcade of nearly 12 autos dressed with streamers and enormous Roosevelt placards, came to a halt at the Station Street depot. Roosevelt addressed the crowd of approximately 1,500 from his auto.

Frustrating the Colonel's initial attempts to speak, several motors remained annoyingly running, whereupon Roosevelt protested, asserting, "I cannot talk against the hum of industry."

Frustrating the Colonel's initial attempts to speak, several motors remained annoyingly running, whereupon Roosevelt protested, asserting, "I cannot talk against the hum of industry."He continued: It is a pleasure to be in Massachusetts and to ask your support in as clean drawn a fight between the people and the professional politicians as there ever was in history. We who fight as progressive Republicans fight more than a factional or party fight. The people have a right to rule themselves, to bring justice, social and industrial, to all in this nation. I want justice for the big and little man alike, with special privilege to none. I am glad to see you and to fight your fight. Put through next Tuesday in Massachusetts what Illinois and Pennsylvania have done (T. R. swept both of those states' primaries). ...I ask Massachusetts to support us in this campaign, not because it is easy, but because it is hard. I appeal to you because this is the only kind of fight worth getting into, the kind of fight where the victory is worth winning and where the struggle is difficult. Here in Massachusetts, as elsewhere, we have against us the enormous preponderance of the forces that win victory in ordinary political contests.

Upon the conclusion of the Colonel's remarks, the motorcade began to proceed, but was impeded by the crowd, surging towards Roosevelt, anxious to shake his hand. The Gazette reported "for a minute it appeared that an accident could not be averted." Fortunately, no such accident occurred. Because Roosevelt had not been anticipated to arrive until after noon, workers from the George E. Keith Company shoe plant on Sumner Avenue had only begun trekking over the Center Street railroad bridge at noon when they came upon the departing hero, who graciously stopped and shook nearly 100 hands. Roosevelt then departed for Taunton, escorted by Spanish-American War veterans and Mayor Fish of the city.

Two days later, on Monday, April 29, one day before the primary, President Taft arrived in a special train in Middleborough at 12:30 to speak before a crowd estimated at 2,000. It is extremely doubtful that Taft would have stopped in town had it not been for Roosevelt's presence a few days earlier. Despite the large crowd, the president was, according to the Gazette, "rather coolly received, there being but a faint cheer." Taft was introduced to the crowd by Town Republican Committee Chairman George W. Stetson. Still reeling from an address made by Roosevelt on April 3 in Louisville, Kentucky, making much of the Republican bosses' support for Taft, the president was clearly on the defensive in Middleborough:

Two days later, on Monday, April 29, one day before the primary, President Taft arrived in a special train in Middleborough at 12:30 to speak before a crowd estimated at 2,000. It is extremely doubtful that Taft would have stopped in town had it not been for Roosevelt's presence a few days earlier. Despite the large crowd, the president was, according to the Gazette, "rather coolly received, there being but a faint cheer." Taft was introduced to the crowd by Town Republican Committee Chairman George W. Stetson. Still reeling from an address made by Roosevelt on April 3 in Louisville, Kentucky, making much of the Republican bosses' support for Taft, the president was clearly on the defensive in Middleborough: Ladies and Gentlemen. I am very sorry to take up your time to listen to a voice nearly gone. I come here from a strong sense of duty. It does not make any real difference to me whether I am re-elected President or not so far as my comfort and happiness and reputation are concerned. I fancy, after having had three years' experience in the Presidency, I could find softer and easier places than that, and I am willing to trust to the future for vindication of my name from the aspersions upon it ... (but) if I permit attacks unfounded upon me, I go back on those whom I am leading in that cause (of progress).

Therefore, I have come here, I cannot help it, and I have got to look into your eyes and tell you the truth as near as know it.

Apparently, many Middleborough voters did make just that "mistake," for the primary vote in Middleborough heavily favored Roosevelt. The primary was called to order promptly at 6 a.m. by clerk Chester E. Weston and "voting was immediately in order." Of 635 Middleborough Republicans voting, 406 gave their preferential vote to Roosevelt, 184 to Taft and a dismal 5 to La Follette. The town also voted nearly 3-1 for the slate of Roosevelt delegates.

Apparently, many Middleborough voters did make just that "mistake," for the primary vote in Middleborough heavily favored Roosevelt. The primary was called to order promptly at 6 a.m. by clerk Chester E. Weston and "voting was immediately in order." Of 635 Middleborough Republicans voting, 406 gave their preferential vote to Roosevelt, 184 to Taft and a dismal 5 to La Follette. The town also voted nearly 3-1 for the slate of Roosevelt delegates. Root (silencing the crowd and leaning from the platform): You have been sent here by your state to vote. If you refuse to do your duty, your alternate will be called upon.

Fosdick: No man on God's earth can make me vote in this convention.

Root then made good his threat and called upon Fosdick's alternate who, due to the contradictory primary results in Massachusetts, happened to be a Taft man. Root continued through the Massachusetts delegation, calling each alternate, whereby Taft succeeded in gaining two votes.

Though the convention was not stopped following the interruption, Roosevelt was livid over the Massachusetts outcome. In the July 6 issue of The Outlook, an irate T. R. labelled his former friend and Secretary of State Root a "modern Autolycus, the snapper-up of unconsidered trifles" who "publicly raped at the last moment (two delegates) from Massachusetts."

The following month, Roosevelt formally bolted the Republican Party to form the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party which took its nickname from the Colonel's statement that he was "as fit as a bull moose." The Progressive platform called for workmen's compensation, minimum wages for women, the establishment of a federal regulatory commission in industry and the prohibition of child labor. The party was financed, in part, by George W. Perkins, a partner in the House of Morgan, who became known as the "Dough Moose." Taft, too, had financial difficulties. When the Republican National Committee made it known that it once again expected the President's elder half-brother Charley to pick up the tab, Charley Taft protested, "I am not made of money!"

Whether it was favoritism for Roosevelt or a genuine progressive Republican impulse in Middleborough, the town favored Progressive Party candidates in 7 of 13 races on the ballot in 1912, giving progressive candidates the town's first vote for president, governor, lieutenant governor secretary of state, state treasurer, 2nd Plymouth District senator (Alvin C. Howes of Middleborough) and Plymouth County commissioner (Lyman P. Thomas of Middleborough).

However, in the long run, progressive Republicanism fared badly, both in Middleborough and the nation as a whole. Though the 1913 elections saw Middleborough give its first place vote to eight progressives in 13 races, it was beginning to lose influence to the Republican Party which began to re-absorb its lost members. In fact, in a three-way race in 1913 for the 7th Plymouth District between Middleborough residents Charles N. Atwood (R), Stephen O'Hara (D) and Lyman P. Thomas (P), Thomas finished third, an indication of progressivism's waning appeal. Running for the same position in 1914, Thomas was the only Progressive candidate on the ballot not to be relegated to a third place finish by the Middleborough voters. In fact, the 1914 elections saw few Progressives run and they even failed to contest the gubernatorial race. Many Bull Moose Progressives not rejoining the Republican Party in 1914 found solace in such candidates as progressive-minded David I. Walsh, the successful-Democratic candidate for governor in 1914 and 1915.

Roosevelt's declination of the 1916 Progressive presidential nomination and his endorsement of fence-straddling Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes effectively mended the breach between Republicans and Bull Moose Progressives. In the 1916 elections, Middleborough voted overwhelmingly for Hughes, who received 743 votes to Wilson's 476. The Democratic share of the 1916 Middleborough vote, however, was nearly 35% greater that the Democratic share in 1912, while the Republican share was down 12.5% from the combined Republican-Progressive share of 1912, an indication that many Middleborough Bull Moose Progressives had moved to the Democratic Party by 1916.

In a fitting epitaph for Bull Moose Progressivism, Roosevelt wrote James R. Garfield, son of President Garfield and Roosevelt's secretary of the interior: "We have fought the good fight, we have kept the faith and have nothing to regret."

Illustrations:

1912 Presidential Vote by County courtesy photobucket.com

+of+Smoky+Mountains+018.jpg)

0 comments:

Post a Comment