Saturday, December 24, 2011

Christmas, 1940

In 1940, Middleborough High School Latin teacher Herbert Wilber decorated his classroom with greenery over the chalkboard and a small lighted white pine tree set on a table in the corner. The simple but effective decorations provided a warm and inviting aspect to the otherwise austere classroom. The room was located on the top floor of Middleborough High School, now the Early Childhood Education Center, on North Main Street.

Friday, December 23, 2011

The Stories in the Stones: Reverend Sylvanus Conant

I am pleased to offer the following post by Middleborough educator Jeff Stevens as part of an on-going series written for the Middleboro Gazette on behalf of the Friends of Middleborough Cemeteries. Mr.Stevens is well versed in the history of Middleborough's early cemeteries, and his "The Stories in the Stones" series proposes to consider the rich cultural and social heritage contained within Middleborough's historic cemeteries through the stories of some of those interred within them. It is hoped to post additional stories here as they are written. To learn more about the Friends of Middleborough Cemeteries, or how you can help, click on the icon at the end of the post.

Middleborough’s cemeteries are full of stories. The men and women who founded this town and lived here over the last 300 plus years have left us thousands of gravestones to mark their final resting places. Each stone is often the final sign of the person’s existence. Some exploring in our many historic sources help fill us in on the life stories behind the stones.

The Rev. Silvanus Conant has a large slate stone in the right front section of the Church on the Green Cemetery. He is pictured in his clerical collar, with two angels looking down on him. The stone tells you that he was a “truly evangelic minister” and an “amiable pattern of charity in all its branches”. It then says he died of the smallpox and is buried three miles away. Beside his gravestone is one for his wife, Abigail, who died at age 28 and beside her, a stone for their son, Ezekiah, who died at just seven days old. Is there more to his story?

The History of the Town of Middleboro by Thomas Weston tells us that Rev. Conant was a Harvard grad who was called to be the 4th minister of the Church on the Green after years of congregational infighting between the “New Lights” and the “Old Lights”, conservative and liberal elements. Conant united the two sides and was well loved by his congregation. Judge Peter Oliver attended this church, as did colonial Governors Hutchinson and Bowdoin. Benjamin Franklin visited one Sunday. A contemporary said of him, “He was full of sunshine, radiant with hope, trusting in his God, and believing in man.”

The Rev. Conant was an avid patriot in the time leading up to the American Revolution. He served as a chaplain in a patriot regiment and his inspiring words led to 35 church members volunteering for service.

In 1777-78, Middleborough was struck by the pestilence when smallpox swept into town. The Rev. Conant and eight of his flock died at the “pest house” in the Soule neighborhood and all nine have stones in the Soule Street Smallpox Cemetery on the corner of Soule and Brook Streets. His stone says that he died in “the 58th year of his age and the 33rd of his ministry”. Silvanus Conant may be the only person buried in Middleborough with two gravestones. Thomas Weston reports, “It is said that upon his death there was weeping in every house in town, at the loss of one of their best and dearest friends.” Not a bad legacy for a dedicated minister and enthusiastic American patriot and quite a story behind his two gravestones.

THE STORIES IN THE STONES - The Rev. Silvanus Conant

Jeff Stevens - Friends of Middleborough Cemeteries

Middleborough’s cemeteries are full of stories. The men and women who founded this town and lived here over the last 300 plus years have left us thousands of gravestones to mark their final resting places. Each stone is often the final sign of the person’s existence. Some exploring in our many historic sources help fill us in on the life stories behind the stones.

The Rev. Silvanus Conant has a large slate stone in the right front section of the Church on the Green Cemetery. He is pictured in his clerical collar, with two angels looking down on him. The stone tells you that he was a “truly evangelic minister” and an “amiable pattern of charity in all its branches”. It then says he died of the smallpox and is buried three miles away. Beside his gravestone is one for his wife, Abigail, who died at age 28 and beside her, a stone for their son, Ezekiah, who died at just seven days old. Is there more to his story?

The History of the Town of Middleboro by Thomas Weston tells us that Rev. Conant was a Harvard grad who was called to be the 4th minister of the Church on the Green after years of congregational infighting between the “New Lights” and the “Old Lights”, conservative and liberal elements. Conant united the two sides and was well loved by his congregation. Judge Peter Oliver attended this church, as did colonial Governors Hutchinson and Bowdoin. Benjamin Franklin visited one Sunday. A contemporary said of him, “He was full of sunshine, radiant with hope, trusting in his God, and believing in man.”

The Rev. Conant was an avid patriot in the time leading up to the American Revolution. He served as a chaplain in a patriot regiment and his inspiring words led to 35 church members volunteering for service.

In 1777-78, Middleborough was struck by the pestilence when smallpox swept into town. The Rev. Conant and eight of his flock died at the “pest house” in the Soule neighborhood and all nine have stones in the Soule Street Smallpox Cemetery on the corner of Soule and Brook Streets. His stone says that he died in “the 58th year of his age and the 33rd of his ministry”. Silvanus Conant may be the only person buried in Middleborough with two gravestones. Thomas Weston reports, “It is said that upon his death there was weeping in every house in town, at the loss of one of their best and dearest friends.” Not a bad legacy for a dedicated minister and enthusiastic American patriot and quite a story behind his two gravestones.

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Middleboro Laundry

If one believes this wonderfully dated piece of advertising from the Middleboro Laundry, the local 1950s housewife "broke her heart" trying to iron the perfect dress shirt for her hard to please husband. In despair, she no doubt turned to the services of the Middleboro Laundry. Here her husband scrutinizes the work to ensure it is up to his exacting standards while in the meantime enjoying a cigarette (which rests in an ashtray near his left hand). Compare this with a circa 1880 Victorian trade card from the George H. Doane Hardware Company and you will see that the lot of women had changed little in the intervening 75 years.

The Middleboro Laundry succeeded Swift's Wet Wash Laundry in 1925 and was owned after 1926 by John Grantham. Located on Wareham Street at the Nemasket River, the firm operated throughout the mid-twentieth century as Middleborough's leading laundry.

Illustration:

Middleboro Laundry, Middleborough, MA, ink blotter, mid-20th century

Thursday, December 1, 2011

Book Signing at Somethin's Brewin' Book Cafe

Join me this Saturday from 10 a. m. to 11.45 a. m. at Somethin's Brewin' Book Cafe in Lakeville where I will be signing copies of South Middleborough: A History.

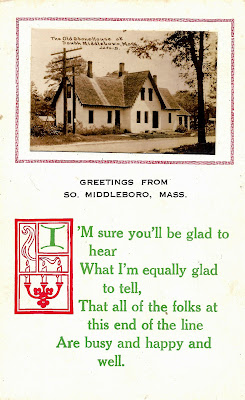

Illustration:

"The Old Stone House", real photo postcard, c. 1920

This postcard features a small photograph of the distinctive Stone House at South Middleborough. Long a landmark in the South Middleborough community, the Stone House was named for the material used in its construction.

The Work of the Victorian Constable

Though Middleborough’s law enforcement agents prior to the reorganization of the Middleborough Police Department in 1909 may have been virtually preoccupied with cases of liquor law violations as noted in the two previous posts, other crimes were on the constabulary’s agenda, as well.

As with liquor laws, there remained a strong social imperative to prosecute laws based upon public morality. Thanks to the efforts of organizations such as the Law & Order League, and others, Middleborough’s Victorian police force engaged in maintaining the sacredness of the Sabbath through enforcement of Sunday “blue laws”. In 1881, the Middleboro Gazette somewhat tongue-in-cheek called for the establishment of a day police, “as employment can be furnished in the way of looking after boys, especially on the Sabbath. ‘The woods are full of ‘em.’” One of Herbert L. Leonard’s first actions as Chief of Police in May, 1901, was to notify local lunch counter operators that they would be required to remain closed on Sundays, prompting one local newspaper to ask “where can a visitor get something to eat on the Sabbath when it is past dinner time at the hotels?”

(Ironically, however, in January, 1886, when local constables arrested a local member of the Salvation Army “for disturbing the peace by playing the hallelujah organ in the street”, Judge Vaughan quickly dismissed the case upon the grounds that the gentleman “had disturbed no one to such an extent as to warrant his holding the defendant for trial”).

(Ironically, however, in January, 1886, when local constables arrested a local member of the Salvation Army “for disturbing the peace by playing the hallelujah organ in the street”, Judge Vaughan quickly dismissed the case upon the grounds that the gentleman “had disturbed no one to such an extent as to warrant his holding the defendant for trial”).

Despite this preoccupation with the enforcement of public morality laws, the early Middleborough police grappled with more serious crimes, most commonly burglary and horse thievery.

Burglaries occurred throughout the period preceding 1909 with the most notorious being the robbery of the town safe in 1871. A string of burglaries occurring in the years around 1880 prompted many residents to arm themselves, and a mini-boom in the sale of firearms was noted in May, 1880. One of those arming himself was grocer Ira Tinkham who in the fall of 1882 used his weapon to fire upon an intruder. In November, 1887, a North Middleborough resident similarly fired upon suspected hen thieves who “left hurriedly.”

The increased number of guns in homes, however, would create its own issues as reported by the local press in January, 1888. “One of the ‘didn’t-know-it-was-loaded’ idiots lives at North Middleboro and one day last week let his gun go off in the sitting room of his house, much to the damage of his furniture and fright of the other occupants of the building. No one was hit by the shot.”

Yet another series of high profile burglaries during the winter of 1885-86 further unsettled the community, particularly following the invasion of elderly Hartley Wood’s home by masked burglars who tied up Wood and his sister while burglarizing the home. So reprehensible was the crime that Middleborough Selectmen offered a $500 reward for the capture and conviction of the perpetrators.

Another frequent crime was that of horse thieving which appears to have peaked during the mid-1880s when Selectmen offered another substantial $500 reward for information leading to the conviction of an unknown horse thief then active in town. “…The town fathers propose to break up the stealing business because it is in their power to do so.” Despite the reward, little concrete information was forthcoming, and the summer of 1887 witnessed a number of horse thefts affecting “several of the well-to-do farmers” in town, including Eleazer Thomas at Rock. Horse thieving would remain a fairly common crime during this era, though occasional lulls in such criminal activity were noted as in June, 1889.

Petty crimes were part of the local constabulary’s work, as well. In October, 1889, the Muttock schoolhouse was ransacked. “The vandals, if detected, ought to be turned over to the tender mercies of the scholars for about an hour,” commented the local newspaper.

Flower thieves struck during the summer of 1885, stealing plants and returning them at night, leading the Middleboro News to quip, “If the party who stole the geranium and pot from Center Street a few nights since, will call at the house, they can have the saucer belonging to the pot.” Similarly, fruit thieves were noted during the autumns of 1885 and 1887, stealing barrels of apples and vegetables left untended overnight.

Clothes were stolen from clotheslines at North Middleborough (February, 1887) and elsewhere (February, 1890), including the family washes of Edward O. Parker and Charles E. Leonard. Meanwhile, Titicut boys were discovered tipping over stone walls and turning out street lamps (“and storing up legal difficulties for themselves”).

Clothes were stolen from clotheslines at North Middleborough (February, 1887) and elsewhere (February, 1890), including the family washes of Edward O. Parker and Charles E. Leonard. Meanwhile, Titicut boys were discovered tipping over stone walls and turning out street lamps (“and storing up legal difficulties for themselves”).

Because late 19th century convention held that “peddlers are nuisances, sometimes thieves, and frequently sell their customers rather than the goods”, itinerant salesmen were the frequent subjects of police observation. Middleborough generally took a firm approach towards unlicensed peddlers, ordering them out of town. Tramps were more often than not treated in a similar fashion.

More serious and more violent crimes were fortunately uncommon. Though incendiarism, or arson, was a rare occurrence, in 1875, an arsonist was believed to be at work. One local newspaper’s advice: “Shoot him.” Domestic violence was not unknown, with cases noted in March, 1886, and April, 1904.

The most serious threat to local law and order, however, came in 1903 with the Independence Day rioting of that year, during which Deputy Sheriff Everett T. Lincoln was shot in the face and Night Watchman George Hatch was forced to flee before a rampaging mob. The town was ultimately charged $455 “for police work in connection with the alleged celebration”, a princely sum in those days. District Court Judge Kelly who presided over the initial trial of nine defendants implicated in the rioting, took a hardline approach and suggested that “if the officers had sprinkled the town house steps with a few prostrate bodies from the crowd, they would have done the right thing.” Middleborough residents initially agreed, though once the sentences were to be handed down, many urged clemency for the convicted rioters.

While the 1903 riots greatly disturbed the community, they ultimately contributed to helping reform the system of local police protection. Six years after the riots, the administration of the Middleborough Police Department would be officially reorganized in 1909, and it is from that time that the modern Middleborough Police Department is said to date.

Illustrations:

"The Norwich Citadel Concertina Band", picture postcard (detail), c. 1907.

Concertinas were popular instruments in the early Salvation Army movement as seen in this photograph of a Salvation Army band based in Norwich, England. In 1886 when Middleborough constables arrested a Salvation Army member for playing a "hallelujah organ" in the streets, the instrument in question was undoubtedly a concertina. Judge Francis M. Vaughan found the disruption caused by the concertina playing did not warrant the defendant's arrest and he dismissed the case.

"Pegs", photograph by donnamarinje, July 27, 2007, republished under a Creative Commons license.

As with liquor laws, there remained a strong social imperative to prosecute laws based upon public morality. Thanks to the efforts of organizations such as the Law & Order League, and others, Middleborough’s Victorian police force engaged in maintaining the sacredness of the Sabbath through enforcement of Sunday “blue laws”. In 1881, the Middleboro Gazette somewhat tongue-in-cheek called for the establishment of a day police, “as employment can be furnished in the way of looking after boys, especially on the Sabbath. ‘The woods are full of ‘em.’” One of Herbert L. Leonard’s first actions as Chief of Police in May, 1901, was to notify local lunch counter operators that they would be required to remain closed on Sundays, prompting one local newspaper to ask “where can a visitor get something to eat on the Sabbath when it is past dinner time at the hotels?”

(Ironically, however, in January, 1886, when local constables arrested a local member of the Salvation Army “for disturbing the peace by playing the hallelujah organ in the street”, Judge Vaughan quickly dismissed the case upon the grounds that the gentleman “had disturbed no one to such an extent as to warrant his holding the defendant for trial”).

(Ironically, however, in January, 1886, when local constables arrested a local member of the Salvation Army “for disturbing the peace by playing the hallelujah organ in the street”, Judge Vaughan quickly dismissed the case upon the grounds that the gentleman “had disturbed no one to such an extent as to warrant his holding the defendant for trial”).Despite this preoccupation with the enforcement of public morality laws, the early Middleborough police grappled with more serious crimes, most commonly burglary and horse thievery.

Burglaries occurred throughout the period preceding 1909 with the most notorious being the robbery of the town safe in 1871. A string of burglaries occurring in the years around 1880 prompted many residents to arm themselves, and a mini-boom in the sale of firearms was noted in May, 1880. One of those arming himself was grocer Ira Tinkham who in the fall of 1882 used his weapon to fire upon an intruder. In November, 1887, a North Middleborough resident similarly fired upon suspected hen thieves who “left hurriedly.”

The increased number of guns in homes, however, would create its own issues as reported by the local press in January, 1888. “One of the ‘didn’t-know-it-was-loaded’ idiots lives at North Middleboro and one day last week let his gun go off in the sitting room of his house, much to the damage of his furniture and fright of the other occupants of the building. No one was hit by the shot.”

Yet another series of high profile burglaries during the winter of 1885-86 further unsettled the community, particularly following the invasion of elderly Hartley Wood’s home by masked burglars who tied up Wood and his sister while burglarizing the home. So reprehensible was the crime that Middleborough Selectmen offered a $500 reward for the capture and conviction of the perpetrators.

Another frequent crime was that of horse thieving which appears to have peaked during the mid-1880s when Selectmen offered another substantial $500 reward for information leading to the conviction of an unknown horse thief then active in town. “…The town fathers propose to break up the stealing business because it is in their power to do so.” Despite the reward, little concrete information was forthcoming, and the summer of 1887 witnessed a number of horse thefts affecting “several of the well-to-do farmers” in town, including Eleazer Thomas at Rock. Horse thieving would remain a fairly common crime during this era, though occasional lulls in such criminal activity were noted as in June, 1889.

Petty crimes were part of the local constabulary’s work, as well. In October, 1889, the Muttock schoolhouse was ransacked. “The vandals, if detected, ought to be turned over to the tender mercies of the scholars for about an hour,” commented the local newspaper.

Flower thieves struck during the summer of 1885, stealing plants and returning them at night, leading the Middleboro News to quip, “If the party who stole the geranium and pot from Center Street a few nights since, will call at the house, they can have the saucer belonging to the pot.” Similarly, fruit thieves were noted during the autumns of 1885 and 1887, stealing barrels of apples and vegetables left untended overnight.

Clothes were stolen from clotheslines at North Middleborough (February, 1887) and elsewhere (February, 1890), including the family washes of Edward O. Parker and Charles E. Leonard. Meanwhile, Titicut boys were discovered tipping over stone walls and turning out street lamps (“and storing up legal difficulties for themselves”).

Clothes were stolen from clotheslines at North Middleborough (February, 1887) and elsewhere (February, 1890), including the family washes of Edward O. Parker and Charles E. Leonard. Meanwhile, Titicut boys were discovered tipping over stone walls and turning out street lamps (“and storing up legal difficulties for themselves”). Because late 19th century convention held that “peddlers are nuisances, sometimes thieves, and frequently sell their customers rather than the goods”, itinerant salesmen were the frequent subjects of police observation. Middleborough generally took a firm approach towards unlicensed peddlers, ordering them out of town. Tramps were more often than not treated in a similar fashion.

More serious and more violent crimes were fortunately uncommon. Though incendiarism, or arson, was a rare occurrence, in 1875, an arsonist was believed to be at work. One local newspaper’s advice: “Shoot him.” Domestic violence was not unknown, with cases noted in March, 1886, and April, 1904.

The most serious threat to local law and order, however, came in 1903 with the Independence Day rioting of that year, during which Deputy Sheriff Everett T. Lincoln was shot in the face and Night Watchman George Hatch was forced to flee before a rampaging mob. The town was ultimately charged $455 “for police work in connection with the alleged celebration”, a princely sum in those days. District Court Judge Kelly who presided over the initial trial of nine defendants implicated in the rioting, took a hardline approach and suggested that “if the officers had sprinkled the town house steps with a few prostrate bodies from the crowd, they would have done the right thing.” Middleborough residents initially agreed, though once the sentences were to be handed down, many urged clemency for the convicted rioters.

While the 1903 riots greatly disturbed the community, they ultimately contributed to helping reform the system of local police protection. Six years after the riots, the administration of the Middleborough Police Department would be officially reorganized in 1909, and it is from that time that the modern Middleborough Police Department is said to date.

Illustrations:

"The Norwich Citadel Concertina Band", picture postcard (detail), c. 1907.

Concertinas were popular instruments in the early Salvation Army movement as seen in this photograph of a Salvation Army band based in Norwich, England. In 1886 when Middleborough constables arrested a Salvation Army member for playing a "hallelujah organ" in the streets, the instrument in question was undoubtedly a concertina. Judge Francis M. Vaughan found the disruption caused by the concertina playing did not warrant the defendant's arrest and he dismissed the case.

"Pegs", photograph by donnamarinje, July 27, 2007, republished under a Creative Commons license.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

+of+Smoky+Mountains+018.jpg)