Showing posts with label famous visitors. Show all posts

Showing posts with label famous visitors. Show all posts

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

The Inhospitable Hotelkeeper

Jeremiah (“Jerry”) Cohan (1848-1917), father of George M. Cohan, was a noted vaudevillian during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Though Cohan would later be best known as one of the “Four Cohans” which also included his wife Helen (“Nellie”) Costigan Cohan, son George and daughter Josie, Cohan toured successfully as a solo performer during the 1870s and 1880s, visiting many cities and small towns, including Middleborough. Though the date and details of Cohan’s visit are not known, it probably occurred during the mid-1870s. What is known is that Cohan enjoyed a less than satisfactory stay at one of the local hostelries, thanks to an inhospitable hotelkeeper, with Cohan later leaving his experience on record. The hotelkeeper in question was in all probability Levi B. Miller, who was proprietor of the Nemasket House on North Main Street during the period that Cohan is likely to have visited and who had previously kept a hotel at Malden, Massachusetts. Miller was born in Maine (thereby fitting Cohan’s characterization as a “’Way Down East’ landlord”). The daughter mentioned would have been Hattie Miller. Though Cohan may have felt poorly treated by the Millers’ lack of hospitality, he also found amusement in their country ways as indicated by the following account which appeared in the New York Times in 1903:

Jerry J. Cohan, of the Four Cohans, commenced his career when he was a boy about sixteen years old. He was a dancer, and in those days considered the champion clog dancer of the country. Mr. Cohan travelled with the Harrigan Hibernica Company, and besides doing his dancing specialty, also lectured on the panorama used in the show. They played many cities and towns from the Atlantic to the Pacific and seldom overlooked a “stand,” whether it was on the map or not and even if obliged to play in the school house. In relating his experience Mr. Cohan tells of many funny incidents that have happened en route; one in particular is concerning the town of Middleboro, Mass., where it is alleged the author of the “Country Circus” got his idea for that once famous play.

“There were about fifteen people in our company,” relates Mr. Cohan, “and we were all obliged to stop at one hotel. At the dinner table all our company had been seated, including Mrs. Cohan, when I appeared in the dining room, and the landlord’s daughter, who was head waitress, assistant, and, in fact, the entire force of waiters, insisted ‘that I set at a separate table.’ I did.

“This caused a great deal of merriment among the folks, and I decided for the fun of the thing to raise Cain with the proprietor, the girl’s father, so when the dinner was over I hurried to the office and confronted the “Way Down East” landlord and started in to the full extent of my ability. For fully ten minutes I roasted, stormed, and swore at the treatment I received and, after being thoroughly exhausted, I quit. To my surprise the old landlord yawned, stretched his arms over his head, and replied:

“'Wa’ll, I don’t know as your talk is goin’ to scare anyone ‘round here.'

“After the laughter died out I asked for writing paper and envelopes and was informed by Mr. Hotelkeeper that he did not run a stationery store. Oh! The place was an exceptional hit to all of us. Harry Steele, one of our company, asked to be called at 7 A. M. and was informed that he would be called when they saw fit, but we were all obliged to wake up at 5:30 A. M. and catch an early train. When we came down stairs to the office the county Sheriff stood at the desk until all our board bills were settled, and then we departed wondering when we would play Middleboro again.”

Illustration:

The Four Cohans, photograph, 1888.

The photograph depicts Jeremiah and Helen Cohan with their son George M. and daughter Josie about 10 years after Mr. and Mrs. Cohan visited Middleborough. The foursome would later become nationally famous as the "Four Cohans", and Jerry would draw upon his experience in Middleborough when performing the country "rube".

Source:

New York Times, “Stageland Gleanings from Here and There”, May 24, 1903

Thursday, September 23, 2010

John L. Sullivan Visits Middleborough, 1915

Though boxer John L. Sullivan (1858-1918) had last been considered world heavyweight champion in 1892, he still retained celebrity status in November, 1915, when he was invited to speak in Middleborough by the Unitarian Church Men's Club.

|

John L. Sullivan, photograph, late 19th century |

Described as the first celebrity athlete, John Lawrence Sullivan had been born in Roxbury, Massachusetts, in 1858 to Irish immigrants Michael and Cathleen Sullivan. Growing to local prominence as the "Boston Strongboy", Sullivan later toured nationally, winning over 450 fights in his career and garnering a national reputation as a bare-knuckled boxer. Sullivan parlayed his athletic prowess into a million dollar fortune and he developed a devoted following in both the sporting and the Irish-American communities.

Following his defeat on September 7, 1892, at the hands of James ("Gentleman Jim") Corbett, Sullivan retired to a farm on Hancock Street in Abington, Massachusetts, though he subsequently took part in a number of exhibition matches after that date. He later worked at a variety of occupations including stage actor, sports reporter and public speaker.

It is in this last role that Sullivan was invited to Middleborough. A committee of the Unitarian Church Men's Club visited Sullivan at his Abington home where the extended an invitation - readily accepted by Sullivan - to speak in Middleborough.

The Sullivan who appeared in Middleborough, however, was not the Sullivan recalled by most, his corpulent figure a product of a lifetime of overindulgence in food, alcohol and tobacco. James H. Creedon later recalled Sullivan at the meeting chain smoking cigars. "He had a wonderful breathing system, as his lung power when smoking a cigar caused the fire to slide up the wrapper of the cigar with great speed. A cigar was burned in a short while, under his expert puffing." In order to keep pace with Sullivan's habit, Walter L. Beals "supplied [Sullivan] with a fresh smoke as he burned them, one after another."

Interestingly, Sullivan seems to have spoken to the gathering about nearly everything except boxing. At the time, tensions were mounting between America and Pancho Villa in Mexico, and both that subject as well as developments in the European war were addressed by Sullivan. "He also had a word to say about the liquor question, which at that time was pretty much a discussed issue, and he felt he was a competent speaker on the subject, having played on both sides." The correspondent at the November meeting remarked that he former boxer "was definitely 'on the wagon,' during the era of his Middleboro visit." Sullivan, in fact, by that time had become a noted spokesperson for temperance, speaking before many church groups on the topic.

Sullivan died two and a half years later in February, 1918.

Source:

Brockton Enterprise, "Recall Visit of 'John L.", February 9, 1949

Source:

Brockton Enterprise, "Recall Visit of 'John L.", February 9, 1949

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

Presidents Grant and Cleveland in Middleborough

A reader recently brought to my attention the 1874 visit of President Ulysses S. Grant to Middleborough. To this may be added the visit of another, Grover Cleveland.

A reader recently brought to my attention the 1874 visit of President Ulysses S. Grant to Middleborough. To this may be added the visit of another, Grover Cleveland.The novelty of these two presidents visiting Middleborough was the result of two particular circumstances: the rise of Cape Cod as a tourist destination during the latter half of the 19th century, and the fact that all passengers destined to Cape Cod from New York and points south were required to change trains at Middleborough - even presidents.

In late August, 1874, Grant was enroute to Martha's Vineyard. Presumably, he took the boat train as he was met at Fall River (where boats traditionally docked and connected with the Boston trains) by Massachusetts Governor Talbot and a large reception to welcome him to Massachusetts. Included in the party were also the Vice-President, Surgeon General and other officials.

The party arrived at Middleborough where it was required to change trains for Woods Hole near one in the afternoon "and received a warm greeting from a large crowd that had gathered at the depot." While the headline carried at the time in the New York Times at the time indicated that President Grant was given a reception at Middleborough, the newspaper failed to provide any details, and no local record is known to exist.

The arrangement of trains also later led President Grover Cleveland to visit the Middleborough depot en route to and returning from his home at Gray Gables on Buzzards Bay in Bourne. In 1892, following his first term in office, Cleveland was required to swap trains on one return journey from the Cape in September of that year.

The arrangement of trains also later led President Grover Cleveland to visit the Middleborough depot en route to and returning from his home at Gray Gables on Buzzards Bay in Bourne. In 1892, following his first term in office, Cleveland was required to swap trains on one return journey from the Cape in September of that year.When the ex-President changed cars at Middleborough several men on the platform stepped forward and shook his hand cordially, and Mr. Cleveland shook theirs cordially in return. The trip from Buzzard's Bay to Fall River was a quick one. Occasionally people in passing through the train recognized Mr. Cleveland and greeted him cordially.

When Cleveland was reelected to a second term, he, unlike Grant, was not required when returning from Gray Gables for the summer in October, 1894, to deboard the train at Middleborough in order to switch to the New York train as he was provided with a private car by the directors of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad. Additionally, greater security was maintained since in the interim between Grant's 1874 visit and Cleveland's return journey in 1894, President James Garfield had been shot on July 2, 1881, by a disgruntled office seeker and died eleven weeks later. The President had been waiting for a train in the Baltimore & Potomac Railroad station in Washington.

For Cleveland's return journey in 1894, he was accompanied by "Mrs. Cleveland, Ruth, and Esther, the President's sister, Miss Rose Cleveland; Mrs. Perrine and nurse, maid, and Secret Service men." The train ran as an express from Gray Gables to Middleborough where it was likely switched to the Taunton track and run as an express to Providence where it was attached to the rear of the New York train. It is unlikely that many Middleborough residents at the time even knew of the occupant of the private car.

Sources:

New York Times, "The President in Massachusetts", August 28, 1874; "Mr. Cleveland Coming", September 30, 1982; "The President Due Here To-Day", October 23, 1894

Sunday, January 31, 2010

"Bull Moose" Progressivism in Middleborough & Lakeville, 1912

The following item is posted in response to a query I had regarding President William Howard Taft's 1912 visit to Middleborough. The article was originally published in the Middleboro Gazette and republished in the Middleborough Antiquarian in May, 1989.

Though progressive Republicanism was never as influential along the East Coast as it was in the West and Midwest, it did create an enormous pull on sympathies of Middleborough voters. At the start of this century, as many of the state's urban voters began taking to the Democratic Party, many rural communities in southeastern Massachusetts, including Middleborough, began developing a progressive Republican bent. The high water mark of progressive Republicanism in Middleborough was the brief period of 1912-13. During that time, the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party, under the aegis of Theodore Roosevelt, exerted a tremendous impact upon the political life of both the town and the nation. The 1912 presidential campaign brought both Roosevelt and President William Howard Taft to Middleborough in a clash of progressive and conservative Republicanism. The 1914 elections, however, sounded the death knell for Bull Moose Progressivism in Middleborough as previously disaffected progressive Republicans returned to the fold of a liberalizing Republican Party or joined the ranks of the burgeoning Democratic Party.

Though progressive Republicanism was never as influential along the East Coast as it was in the West and Midwest, it did create an enormous pull on sympathies of Middleborough voters. At the start of this century, as many of the state's urban voters began taking to the Democratic Party, many rural communities in southeastern Massachusetts, including Middleborough, began developing a progressive Republican bent. The high water mark of progressive Republicanism in Middleborough was the brief period of 1912-13. During that time, the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party, under the aegis of Theodore Roosevelt, exerted a tremendous impact upon the political life of both the town and the nation. The 1912 presidential campaign brought both Roosevelt and President William Howard Taft to Middleborough in a clash of progressive and conservative Republicanism. The 1914 elections, however, sounded the death knell for Bull Moose Progressivism in Middleborough as previously disaffected progressive Republicans returned to the fold of a liberalizing Republican Party or joined the ranks of the burgeoning Democratic Party.Bull Moose Progressivism, itself, was an indirect consequence of a political maneuver made by Roosevelt. Following election to the White House in his own right in November, 1904,the progressive Roosevelt renounced a third term for himself as president in the "bully pulpit," though this did not prevent him from personally hand-picking his successor - Secretary of War William Howard Taft. Despite a year-long African safari with his son Kermit followed by a triumphal European tour, Roosevelt could not arrest the presidential itch and by February, 1912, considering Taft disloyal to the cause of progressive Republicanism, Roosevelt declared, "My hat is in the ring" for a third presidential term.

Vying with Roosevelt for the Republican bid were progressive Wisconsin Senator Robert "Battle Bob" La Follette, who sought to deprive Roosevelt of the mantle of progressive Republicanism, and President Taft, candidate of the conservative or "stand pat" Republicans. La Follette virtually disqualified himself at the beginning of February with a rambling and incoherent speech, a consequence of overwork, while Taft had his own drawbacks. Taft's tendency to fall asleep in public (once, as a front row mourner, he drifted off at a funeral to the utter horror of his military aide, Archie Butt), his obvious corpulence, his heavy reliance upon arch-conservative Speaker of the House "Uncle Joe" Cannon of Massachusetts and his responsibility for the loss of the House Republican majority in the 1910 election were all detriments to the Taft campaign. Nor did it help that the president self-deprecatingly referred to himself as both a "cornered rat" and a "straw man" in the campaign.

Vying with Roosevelt for the Republican bid were progressive Wisconsin Senator Robert "Battle Bob" La Follette, who sought to deprive Roosevelt of the mantle of progressive Republicanism, and President Taft, candidate of the conservative or "stand pat" Republicans. La Follette virtually disqualified himself at the beginning of February with a rambling and incoherent speech, a consequence of overwork, while Taft had his own drawbacks. Taft's tendency to fall asleep in public (once, as a front row mourner, he drifted off at a funeral to the utter horror of his military aide, Archie Butt), his obvious corpulence, his heavy reliance upon arch-conservative Speaker of the House "Uncle Joe" Cannon of Massachusetts and his responsibility for the loss of the House Republican majority in the 1910 election were all detriments to the Taft campaign. Nor did it help that the president self-deprecatingly referred to himself as both a "cornered rat" and a "straw man" in the campaign.In contrast, the dynamic T. R was enormously popular with the rank and file Republican voters and he hoped to win numerous delegates in the 13 presidential primaries, 1912 being the maiden year of the primary system. The Massachusetts primary was scheduled for Tuesday, April 30, and both Roosevelt and Taft spent much time in the commonwealth posturing for the event.

On Friday evening, April 26, President Taft gave a major address in Boston which left him physically and emotionally exhausted. Taft told the Boston audience, "I do not want to fight Theodore Roosevelt, but sometimes a man in a corner fights. I am going to fight." At Boston, Taft raised the third term issue, concerned that Colonel Roosevelt "should not have as many terms as his natural life will permit." Ironically, it was just this issue which was responsible for a foiled assassination attempt of Roosevelt by a disgruntled New York bartender in October in Milwaukee.

Roosevelt was the first of the two contenders to speak in Middleborough, arriving April 27 , three days before the primary. Roosevelt's stop in Middleborough was part of his second trip to New England since the beginning of April. Interrupting the New England tour was a side journey to Kansas and Nebraska which nearly cost T. R's voice, so strenuous were the speaking engagements. Because of the strain of the tour, Roosevelt knew it would be futile to mount a full-scale railroad car campaign when he returned to New England at the end of April. "It is folly to try to make me continue a car-tail campaign," he said. Consequently, Roosevelt scheduled appearances only at Fall River, New Bedford and Boston for the morning and evening of the 27th. Due to the efforts of the local Roosevelt Club, however, the itinerary was altered to include brief stops in Brockton, Middleborough and Taunton.

Arriving from Brockton one hour before the scheduled arrival time of 12:30, Roosevelt's motorcade of nearly 12 autos dressed with streamers and enormous Roosevelt placards, came to a halt at the Station Street depot. Roosevelt addressed the crowd of approximately 1,500 from his auto.

Frustrating the Colonel's initial attempts to speak, several motors remained annoyingly running, whereupon Roosevelt protested, asserting, "I cannot talk against the hum of industry."

Frustrating the Colonel's initial attempts to speak, several motors remained annoyingly running, whereupon Roosevelt protested, asserting, "I cannot talk against the hum of industry."He continued: It is a pleasure to be in Massachusetts and to ask your support in as clean drawn a fight between the people and the professional politicians as there ever was in history. We who fight as progressive Republicans fight more than a factional or party fight. The people have a right to rule themselves, to bring justice, social and industrial, to all in this nation. I want justice for the big and little man alike, with special privilege to none. I am glad to see you and to fight your fight. Put through next Tuesday in Massachusetts what Illinois and Pennsylvania have done (T. R. swept both of those states' primaries). ...I ask Massachusetts to support us in this campaign, not because it is easy, but because it is hard. I appeal to you because this is the only kind of fight worth getting into, the kind of fight where the victory is worth winning and where the struggle is difficult. Here in Massachusetts, as elsewhere, we have against us the enormous preponderance of the forces that win victory in ordinary political contests.

Upon the conclusion of the Colonel's remarks, the motorcade began to proceed, but was impeded by the crowd, surging towards Roosevelt, anxious to shake his hand. The Gazette reported "for a minute it appeared that an accident could not be averted." Fortunately, no such accident occurred. Because Roosevelt had not been anticipated to arrive until after noon, workers from the George E. Keith Company shoe plant on Sumner Avenue had only begun trekking over the Center Street railroad bridge at noon when they came upon the departing hero, who graciously stopped and shook nearly 100 hands. Roosevelt then departed for Taunton, escorted by Spanish-American War veterans and Mayor Fish of the city.

Two days later, on Monday, April 29, one day before the primary, President Taft arrived in a special train in Middleborough at 12:30 to speak before a crowd estimated at 2,000. It is extremely doubtful that Taft would have stopped in town had it not been for Roosevelt's presence a few days earlier. Despite the large crowd, the president was, according to the Gazette, "rather coolly received, there being but a faint cheer." Taft was introduced to the crowd by Town Republican Committee Chairman George W. Stetson. Still reeling from an address made by Roosevelt on April 3 in Louisville, Kentucky, making much of the Republican bosses' support for Taft, the president was clearly on the defensive in Middleborough:

Two days later, on Monday, April 29, one day before the primary, President Taft arrived in a special train in Middleborough at 12:30 to speak before a crowd estimated at 2,000. It is extremely doubtful that Taft would have stopped in town had it not been for Roosevelt's presence a few days earlier. Despite the large crowd, the president was, according to the Gazette, "rather coolly received, there being but a faint cheer." Taft was introduced to the crowd by Town Republican Committee Chairman George W. Stetson. Still reeling from an address made by Roosevelt on April 3 in Louisville, Kentucky, making much of the Republican bosses' support for Taft, the president was clearly on the defensive in Middleborough: Ladies and Gentlemen. I am very sorry to take up your time to listen to a voice nearly gone. I come here from a strong sense of duty. It does not make any real difference to me whether I am re-elected President or not so far as my comfort and happiness and reputation are concerned. I fancy, after having had three years' experience in the Presidency, I could find softer and easier places than that, and I am willing to trust to the future for vindication of my name from the aspersions upon it ... (but) if I permit attacks unfounded upon me, I go back on those whom I am leading in that cause (of progress).

Therefore, I have come here, I cannot help it, and I have got to look into your eyes and tell you the truth as near as know it.

It is said that all the bosses are supporting me. I deny it. Mr. Roosevelt and I are exactly alike in certain respects, a good deal of human nature in both of us and when we are running for office we do not examine the clothes or the hair or previous condition of anybody that tenders support. But the only way by which he can make true the statement that all the bosses are supporting me and none of the bosses are supporting him but are opposed to him is to give a new definition to "bosses" and that is that every man in politics that is against him is a boss and every man that is for him is a leader.

Following the speech, the train left for Boston amidst cheers as Taft waved a flag. One ironic side note to the Middleborough speech did not bode well for Taft. Upon Taft's arrival, a local man decided to welcome the president with a cheer. "Three cheers for Ted Roosevelt!," he cried. Realizing his gaffe, he quickly corrected himself, "I mean President Taft." Taft, within earshot, remained unruffled. Smiling, he told the would-be cheerleader in his stentorian tone, "Don't make that mistake tomorrow."

Apparently, many Middleborough voters did make just that "mistake," for the primary vote in Middleborough heavily favored Roosevelt. The primary was called to order promptly at 6 a.m. by clerk Chester E. Weston and "voting was immediately in order." Of 635 Middleborough Republicans voting, 406 gave their preferential vote to Roosevelt, 184 to Taft and a dismal 5 to La Follette. The town also voted nearly 3-1 for the slate of Roosevelt delegates.

Apparently, many Middleborough voters did make just that "mistake," for the primary vote in Middleborough heavily favored Roosevelt. The primary was called to order promptly at 6 a.m. by clerk Chester E. Weston and "voting was immediately in order." Of 635 Middleborough Republicans voting, 406 gave their preferential vote to Roosevelt, 184 to Taft and a dismal 5 to La Follette. The town also voted nearly 3-1 for the slate of Roosevelt delegates. Of all 13 primaries, the Massachusetts contest witnessed the closest race between Roosevelt and Taft. Taft took 86,722 Massachusetts votes, followed by Roosevelt's 83,099 and La Follette's 2,058. The popular vote notwithstanding, the Massachusetts outcome was indecisive for, though Taft won the preferential by slightly more than 3,500 (technically making him the victor), Roosevelt's slate of 8 at-large delegates trounced Taft's slate by some 8,000 votes. Roosevelt, perhaps a little disparagingly, wrote his friend, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts: "Well, isn't the outcome in Massachusetts comic? Apparently there were about 80,000 people who preferred Taft, about 80,000 who preferred me and from three to five thousand who, in an involved way, thought they would vote both for Taft and me!"

The final primary was held the first week of June. Of the 13, Roosevelt won nine, losing Wisconsin and North Dakota to La Follette and his native New York and Massachusetts to Taft. As a consequence, Roosevelt received 278 delegates, Taft 48 and La Follette 36.

Because of his victory in the primaries, Roosevelt could joke about the skewed Massachusetts results, but the Massachusetts outcome would cause further clamor at the Republican convention held in Chicago, June 18-22. At Chicago, Taft hoped his control of the National Committee and the southern delegations (whose states did not hold primaries) would offset Roosevelt's popularity.

The first order of convention business was to elect a temporary chairman and the Massachusetts delegation split evenly between Taft-backed Elihu Root and Wisconsin Governor Francis E. McGovern, whose backing by Roosevelt was a concession to appease the La Follette forces. Root squeaked by, 558-501, with the vote of each delegate being taken individually. The close vote set the tone for the remainder of the convention, which the Taft forces intended to dominate by denying Roosevelt's disputation of the credentials of some 250 Taft delegates, and which the Roosevelt forces were determined to keep in turmoil.

During the frequent lulls in convention activity, the New Jersey delegation would rise on cue and begin cheering for Roosevelt. T. R.'s young cousin Nicholas Roosevelt would later recall how the New Jersey delegation would generally be followed by the Massachusetts delegation which, in a cheer led by historian and Harvard professor Albert Bushnell Hart, would shout: "Massachusetts 18! Massachusetts 18! Massachusetts 18! Roosevelt first, last and all the time!" (the 18 referring to the state's number of electoral votes).

On Saturday, June22, nominating began with Taft being nominated by fellow Ohioan Warren G. Harding who, by calling Taft "the greatest progressive of the age," must surely have made Roosevelt apoplectic. The only other name place in nomination was that of La Follette.

Though most Roosevelt delegates abstained from voting at the direction of Roosevelt, there were no serious problems until the vote of the Massachusetts delegation was called. The chairman of the delegation responded that the commonwealth "casts all 18 votes for Taft with 18 abstentions." When the tally was questioned, a roll of the individual Massachusetts delegates was called, the first being Frederick Fosdick, pledged to Roosevelt.

Fosdick: Present, but I refuse to vote. (cheering)

Root (silencing the crowd and leaning from the platform): You have been sent here by your state to vote. If you refuse to do your duty, your alternate will be called upon.

Fosdick: No man on God's earth can make me vote in this convention.

Root (silencing the crowd and leaning from the platform): You have been sent here by your state to vote. If you refuse to do your duty, your alternate will be called upon.

Fosdick: No man on God's earth can make me vote in this convention.

Root then made good his threat and called upon Fosdick's alternate who, due to the contradictory primary results in Massachusetts, happened to be a Taft man. Root continued through the Massachusetts delegation, calling each alternate, whereby Taft succeeded in gaining two votes.

Though the convention was not stopped following the interruption, Roosevelt was livid over the Massachusetts outcome. In the July 6 issue of The Outlook, an irate T. R. labelled his former friend and Secretary of State Root a "modern Autolycus, the snapper-up of unconsidered trifles" who "publicly raped at the last moment (two delegates) from Massachusetts."

Roosevelt refused to consider a compromise candidate such as associate Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes (who would lose to Wilson in 1916) or Missouri Governor Herbert S. Hadley. Said Roosevelt: "I'll name the compromise candidate. He'll be me. I'll name the compromise platform. It will be our platform." Subsequently, Taft won the nomination with 561 votes to Roosevelt's 107, La Follette's 41, Iowa Senator Cummins' 17 and Hughes' 2. However, 344 Roosevelt delegates had abstained from voting.

A week later, the Democratic National Convention was convened in Baltimore and today is notable for being as inharmonious as the Republican Convention of the previous week. In contention for the nomination were House Speaker "Champ" Clark of Missouri, New Jersey reform Governor Woodrow Wilson, Senator Judson Harmon of Ohio and House Majority Leader Oscar Underwood of Alabama. Later in the balloting, the name of Massachusetts Governor Eugene N. Foss, to whom the majority of Massachusetts delegates were pledged, was put forth, but the momentum had already begun to swing towards Wilson, who was selected on the 46th ballot. The selection of Wilson relieved many delegates who had from the start been opposed to Clark, embarrassed by his testimonial for Electric Bitters: "It seemed that all the organs in my body were out of order, but three bottles of Electric Bitters made me all right."

The following month, Roosevelt formally bolted the Republican Party to form the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party which took its nickname from the Colonel's statement that he was "as fit as a bull moose." The Progressive platform called for workmen's compensation, minimum wages for women, the establishment of a federal regulatory commission in industry and the prohibition of child labor. The party was financed, in part, by George W. Perkins, a partner in the House of Morgan, who became known as the "Dough Moose." Taft, too, had financial difficulties. When the Republican National Committee made it known that it once again expected the President's elder half-brother Charley to pick up the tab, Charley Taft protested, "I am not made of money!"

The following month, Roosevelt formally bolted the Republican Party to form the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party which took its nickname from the Colonel's statement that he was "as fit as a bull moose." The Progressive platform called for workmen's compensation, minimum wages for women, the establishment of a federal regulatory commission in industry and the prohibition of child labor. The party was financed, in part, by George W. Perkins, a partner in the House of Morgan, who became known as the "Dough Moose." Taft, too, had financial difficulties. When the Republican National Committee made it known that it once again expected the President's elder half-brother Charley to pick up the tab, Charley Taft protested, "I am not made of money!"

When it was suggested that Taft and Roosevelt cooperate to prevent a Democratic victory, T. R. responded, "I hold that Mr. Taft stole the nomination, and I do not feel like arbitrating with a pickpocket as to whether or not he shall keep my watch."

The 1912 presidential election in Middleborough was basically a repetition of the primary. Though Roosevelt won Middleborough, he lost the state to Wilson. Of 1,358 votes in Middleborough's two precincts, Roosevelt received 545 votes; Wilson sneaked into second place with 378 votes ahead of Taft with 360 votes. Roosevelt, however, was unable to carry the state and, in fact, finished third behind Taft. In total, Wilson won 40 states, Roosevelt six and Taft two.

Whether it was favoritism for Roosevelt or a genuine progressive Republican impulse in Middleborough, the town favored Progressive Party candidates in 7 of 13 races on the ballot in 1912, giving progressive candidates the town's first vote for president, governor, lieutenant governor secretary of state, state treasurer, 2nd Plymouth District senator (Alvin C. Howes of Middleborough) and Plymouth County commissioner (Lyman P. Thomas of Middleborough).

However, in the long run, progressive Republicanism fared badly, both in Middleborough and the nation as a whole. Though the 1913 elections saw Middleborough give its first place vote to eight progressives in 13 races, it was beginning to lose influence to the Republican Party which began to re-absorb its lost members. In fact, in a three-way race in 1913 for the 7th Plymouth District between Middleborough residents Charles N. Atwood (R), Stephen O'Hara (D) and Lyman P. Thomas (P), Thomas finished third, an indication of progressivism's waning appeal. Running for the same position in 1914, Thomas was the only Progressive candidate on the ballot not to be relegated to a third place finish by the Middleborough voters. In fact, the 1914 elections saw few Progressives run and they even failed to contest the gubernatorial race. Many Bull Moose Progressives not rejoining the Republican Party in 1914 found solace in such candidates as progressive-minded David I. Walsh, the successful-Democratic candidate for governor in 1914 and 1915.

Roosevelt's declination of the 1916 Progressive presidential nomination and his endorsement of fence-straddling Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes effectively mended the breach between Republicans and Bull Moose Progressives. In the 1916 elections, Middleborough voted overwhelmingly for Hughes, who received 743 votes to Wilson's 476. The Democratic share of the 1916 Middleborough vote, however, was nearly 35% greater that the Democratic share in 1912, while the Republican share was down 12.5% from the combined Republican-Progressive share of 1912, an indication that many Middleborough Bull Moose Progressives had moved to the Democratic Party by 1916.

In a fitting epitaph for Bull Moose Progressivism, Roosevelt wrote James R. Garfield, son of President Garfield and Roosevelt's secretary of the interior: "We have fought the good fight, we have kept the faith and have nothing to regret."

Click here to hear Roosevelt's "Progressive Covenant with the People" address. Photograph and audio recording courtesy of the Library of Congress. Captioned by Michael J. Maddigan.

Illustrations:

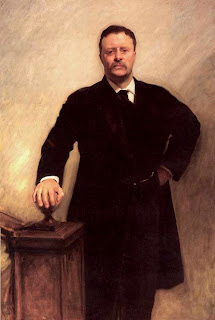

Theodore Roosevelt by John Singer Sargent, oil on canvas, 1903

"Progressive Fallacies", unidentified political cartoon, 1912

In this cartoon from the 1912 presidential election, Theodore Roosevelt has usurped the progressive mantle from Wisconsin senator Robert M. LaFollette who sits sulking on a nearby sofa. Roosevelt is accompanied on the piano by Miss Insurgency, who's contention that Roosevelt sings better than LaFollette was refelctive of the Republican rank and file's view of the former President.

Theodore Roosevelt campaigning, photograph, 1912, courtesy Library of Congress

William Howard Taft, photograph, 1908, courtesy Library of Congress

William Howard Taft, Middleborough, MA, halftone from a photograph taken April 27, 1912

Standing to the left of Taft is George W. Stetson, Middleborough Town Republican Committee Chairman.

"Floor-Manager Taft" by Edward Windsor Kemble, Harper's Weekly, February 12, 1912, pp. 14-15

In this political cartoon, Roosevelt tries to do the "Grizzly Bear" with the "dear old lady" otherwise known as the Republican Party. The cartoon is indicative of the disruption Roosevelt caused in the 1912 Republican campaign.

1912 Presidential Vote by County courtesy photobucket.com

Plymouth and Barnstable Counties had the highest percentage of votes in Massachusetts for Roosevelt.

Saturday, October 17, 2009

Marconi in Middleborough

Following the construction of his wireless telegraphy station at South Wellfleet, Massachusetts, in 1901-02, Gugliemlo Marconi (1874-1937) was a frequent visitor at the Middleborough railroad station where he was required to change trains between Cape Cod and New York. During one such visit, the famous Italian who proved that the sending of telegraphic signals by means of radio waves was possible, was interviewed by a young James F. Creedon in the early 1900s. Many years later, in 1951, Creedon recalled his meeting with the future Nobel Prize winner:

Marconi was a frequent visitor in Middleboro. Not for a social stop, but it so happened he was journeying from his wireless station at Wellfleet to New York where he had headquarters.

There was considerable interest and a bit of newspaper publicity from time to time about what he planned to do. And that activity brought up many inquiries about what might be expected. City newspapers, always alert to delve into the unusual, had many questions to ask about what was going on.

And it happened to be the chore of the Middleboro correspondent, J. F. Creedon, to ask the questions and gather the information from Marconi himself. He was intercepted at the Middleboro railroad station, between the time he arrived on the up-Cape Cod train and the time he took the boat train to Fall River.

At that time he was a comparatively young man, faultlessly dressed, with an attractive fur coat with a fur collar, at this time of year. He had an uneasy way, and during the time he was in Middleboro awaiting the train change he never sought a seat in the station. Instead he busied himself walking the station platform, impatiently awaiting arrival of the other train.

Except that when he was asked about his new communications method, which seemed so unreal then, he would explain its manner of operation and what he expected would develop from it. He was a considerate man and did his best to explain the details to a juvenile writer and questioner, who didn't have too much background in matters electrical to digest it all.

He was co-operative and felt it would go a long way to speed up long distance communications, without wires by land or cables by sea.

Illustration:

Guglielmo Marconi, photograph, early 20th century

Source:

Brockton Enterprise, "Recalls Chat with Marconi", December 13, 1951.

Friday, August 14, 2009

Middleborough Aviation Meeting, 1911

.

“Harry Atwood’s going to fly here” was the phrase that drew the throng

And the speeches went neglected and the speakers were forlorn

For the mighty Harry Atwood was “a tooting’ of his horn.”

Harry Atwood’s going to fly here” was the Shout along the way –

Washington Post, “Atwood Will Not Fly Today”, 1911

Though the Wright Brothers may have achieved manned flight in 1903, the first decade of aviation in America remained inconsistent and seemingly directionless. Stunt-performing exhibition pilots competed with more serious aviators who sought to perfect the art of flying and push the boundaries of the science in order to demonstrate the capabilities of the airplane. Flights were brief and were limited in distance, and were intended primarily to demonstrate a pilot’s skill or to help perfect the design of a particular plane. Flights were also limited in geographic scope, so consequently, when local residents caught their first glimpse of an airplane in flight in late June, 1911, they were understandably enthralled, with all eyes turned naturally to the sky that morning.

Helping promote early aviation locally was native New Englander Harry N. Atwood (1884-1967) who in time developed a large local following in southeastern Massachusetts thanks to family connections in the area (his grandfather Marcus Atwood was a Carver resident). In May, 1911, Atwood enrolled in the Wright Brothers’ flying school at Huffman Prairie outside Dayton, Ohio, where training was rudimentary and consisted of exercises preparatory to brief flights into the air. “After two weeks of training, talking and flying, Harry Atwood graduated. He had completed eighteen lessons and flown for a total of one hour and fifty-five minutes … and in a few weeks he would be a hero.”

Helping promote early aviation locally was native New Englander Harry N. Atwood (1884-1967) who in time developed a large local following in southeastern Massachusetts thanks to family connections in the area (his grandfather Marcus Atwood was a Carver resident). In May, 1911, Atwood enrolled in the Wright Brothers’ flying school at Huffman Prairie outside Dayton, Ohio, where training was rudimentary and consisted of exercises preparatory to brief flights into the air. “After two weeks of training, talking and flying, Harry Atwood graduated. He had completed eighteen lessons and flown for a total of one hour and fifty-five minutes … and in a few weeks he would be a hero.”

In a few weeks, in fact, Atwood became the first pilot to fly over Middleborough and Lakeville when on June 30, 1911, he piloted his plane over the two towns enroute to Fall River and ultimately New London where he proposed viewing the Harvard-Yale crew races. Atwood would later continue from Connecticut to New York City in the process establishing a record for the longest "cross country" flight up to that time. Despite this achievement, it was their first glimpse of an airplane that Middleborough and Lakeville residents found noteworthy.

Those who had their eyes to the sky this morning saw aviator Atwood, who went through here at 7:40, headed south. He was reported out of Bridgewater about 7:30, headed for Middleboro.

Those who had their eyes to the sky this morning saw aviator Atwood, who went through here at 7:40, headed south. He was reported out of Bridgewater about 7:30, headed for Middleboro.

The aeroplane first appeared in the north about 7:35, and it was probably from 600 to 1000 feet in the air. It was making its way, at a good speed, though apparently without effort. The machine passed to the westward of the town, and was observed by many passengers on the trolley cars which arrive here about 8 a. m., as well as by others.

It was also seen at the state sanatorium in Lakeville, where it apparently came close to the ground, and then swooped off over Lake Assawampsett and Long pond, apparently headed for New Bedford.

Atwood’s biographer writes that as the plane flew overhead, “a small boy was the first to see Atwood, and shouted, ‘See the big bird!’ Atwood could hear the applause below.”

Atwood, that summer, would achieve far wider acclaim by becoming the first pilot to land upon the White House lawn (July 14, 1911) and by piloting a record-breaking flight between St. Louis to New York (August 14-25, 1911). On September 3, Atwood was guest of honor at a reception at the King Philip Tavern at Lakeville and he was still at the height of his fame nationally when he appeared on Friday, October 18, 1911, at an air meet in Middleborough.

For some time, Atwood had been looking for a suitable opportunity to display his aviation skills to his relatives, including his grandfather. In October, 1911, Atwood was engaged for a performance at the Brockton Fair, and he believed that timing would be ideal for a demonstration for his family. Two stories survive giving differing views on how Atwood settled upon Middleborough as the locale for his exploit. One relates that Atwood’s manager, Thomas McLaughlin, “a Boston newspaper man”, contacted James H. Creedon of Middleborough who also worked as a journalist and may have been known to McLaughlin. A different tale relates that Atwood, his performance at Brockton having been cancelled on October 5, traveled to Middleborough to visit with his cousin, pharmacist Kenneth L. Childs who proposed the meet. Regardless of which version is correct, Creedon, Childs and Harlas Cushman of Miller Street worked to promote a meet at Middleborough.

In order to prepare for the meet, Atwood toured the countryside about Middleborough, in search of a suitable makeshift landing field. Ultimately, he settled upon Fall Brook Farm, located at the intersection of Wareham and Grove Streets which featured a large, level, cleared field stretching between Wareham and Tispaquin Streets. At the time, the farm was operated as an automobile inn and the proprietor no doubt saw the meet as a means of attracting business.

In order to prepare for the meet, Atwood toured the countryside about Middleborough, in search of a suitable makeshift landing field. Ultimately, he settled upon Fall Brook Farm, located at the intersection of Wareham and Grove Streets which featured a large, level, cleared field stretching between Wareham and Tispaquin Streets. At the time, the farm was operated as an automobile inn and the proprietor no doubt saw the meet as a means of attracting business.

Creedon was named secretary of a committee including Childs, McLaughlin and Edwin C. Cotton of Lynn which promoted the meet, and a number of dignitarires were expected including Governor Eugene N. Foss and Lieutenant Governor Frothingham. Creedon obtained assurances from Atwood’s relatives that they would be present in large numbers, and the town of Carver moved to “make the day a holiday and everyone will head for Middleboro.” The proposed meet generated enormous enthusiasm in town and elsewhere. “The affair was publicized over Cape Cod and through Plymouth county, and considerable interest developed.” Factories and schools made plans to close for the afternoon in order that workers and students would be free to attend. Atwood, himself, helped promote the event, traveling to Carver to visit his grandfather in “a big auto for the time, with wheels which measured 40 inches across and which were almost up to the top of the open body on the car.”

Besides visiting relatives, Atwood spent time preparing his biplane, a Burgess-Wright model, for the meet. Some days before the meet, “a back-firing of the engine broke both propellers and this damage had to be remedied here.” On Sunday, October 13, Atwood gave a few short exhibition flights, and on either the 13th or 14th he took a longer flight to New Bedford accompanied by Edwin C. Cotton. Although the New York Times reported on October 16 that Atwood's flight from New Bedford to Middleborough took only twenty minutes, other sources reported that on the return flight, Atwood had broken the flight, landing in a large field in the vicinity of one of the Quitticas ponds in Lakeville in order to make adjustments. The advent of the temporarily grounded plane was a novelty and not surprisingly created a stir.

Besides visiting relatives, Atwood spent time preparing his biplane, a Burgess-Wright model, for the meet. Some days before the meet, “a back-firing of the engine broke both propellers and this damage had to be remedied here.” On Sunday, October 13, Atwood gave a few short exhibition flights, and on either the 13th or 14th he took a longer flight to New Bedford accompanied by Edwin C. Cotton. Although the New York Times reported on October 16 that Atwood's flight from New Bedford to Middleborough took only twenty minutes, other sources reported that on the return flight, Atwood had broken the flight, landing in a large field in the vicinity of one of the Quitticas ponds in Lakeville in order to make adjustments. The advent of the temporarily grounded plane was a novelty and not surprisingly created a stir.

The place where he had landed the machine was two miles from the Middleboro-New Bedford trolley line, but that did not faze some 2000 persons who flocked to the field to get a look at it. They had to walk in some distance from the highway to get their look during the day it was there.

Later, Atwood “took to the air and an old time account relates he made a perfect flight and remained in the air about 12 minutes.” Three days later, on the 16th, Atwood was in New York securing “a new motor and propellers … should their use be necessary.” And while early reports of the meet indicated that Atwood would “instruct a few pupils here in the days before and after the meeting,” it’s not clear whether he did so. One eager would-be aviator, however, C. E. Jenney of Indianapolis who was summering nearby approached Atwood at his Middleborough hotel and requested to be taken on as a student.

Weather conditions on the day of the meet proved unfavorable, with wind and rain, and though a crowd was present, attendance was estimated at only 400 spectators. Atwood delayed his flights in hopes that the weather would abate. Not only the wind, but the rain posed potential problems for a fabric-winged plane. (In 1911 at the Dominguez Field exhibition at Los Angeles, a Burgess-Wright plane flown by Howard Gill would crash during a storm after the fabric of the plane had become so saturated with rain that the extra weight brought the airplane down). “This wait didn’t bother anyone, as they had a chance to view the crude single engined craft, with a kitchen chair for the pilot’s seat; with bed sheeting covering the wings of the biplane to sustain flight. The struts were of wood, and a ‘stick’ was the instrument for raising and lowering it, while another one aided in handling its turns and side motion.”

Weather conditions on the day of the meet proved unfavorable, with wind and rain, and though a crowd was present, attendance was estimated at only 400 spectators. Atwood delayed his flights in hopes that the weather would abate. Not only the wind, but the rain posed potential problems for a fabric-winged plane. (In 1911 at the Dominguez Field exhibition at Los Angeles, a Burgess-Wright plane flown by Howard Gill would crash during a storm after the fabric of the plane had become so saturated with rain that the extra weight brought the airplane down). “This wait didn’t bother anyone, as they had a chance to view the crude single engined craft, with a kitchen chair for the pilot’s seat; with bed sheeting covering the wings of the biplane to sustain flight. The struts were of wood, and a ‘stick’ was the instrument for raising and lowering it, while another one aided in handling its turns and side motion.”

Eventually, the wind stilled enough for Atwood to attempt a flight, and he would ultimately complete three flights that day. During the first flight, Atwood circled the field at Fall Brook before flying over Tispaquin Pond, and then returning to the field. It was probably on this flight that

he ran into a heavy rain shower, which continued several minutes. He said when he alighted that the rain drops struck his face like bullets. He did some skillful work in fancy flying which thrilled the crowd. He found the air dangerous, however, and somewhat squally.

For the subsequent two flights, Atwood invited a passenger along on each. Mrs. Edwin C. Cotton accompanied Atwood on his second flight of five minutes for what was her first time in the air. Completely exhilarated by the experience, she informed reporters that “it was perfectly delightful, and I don’t ever remember of enjoying anything so much.” Atwood’s second passenger that afternoon was his chauffeur, Leo Malanson.

Following Atwood’s performance, his plane was left behind at Fall Brook Farm where it was “drawn up behind a barn and lashed to the ground,” likely attracting the curious. Later, “a representative of the factory” arrived in town to disassemble the plane which finally, on November 4, was shipped from Middleborough. While Atwood never again flew at Middleborough, he did continue to visit the area at least. In November, 1911, he is recorded as having visited friends in town in company with Edwin C. Cotton.

Following Atwood’s performance, his plane was left behind at Fall Brook Farm where it was “drawn up behind a barn and lashed to the ground,” likely attracting the curious. Later, “a representative of the factory” arrived in town to disassemble the plane which finally, on November 4, was shipped from Middleborough. While Atwood never again flew at Middleborough, he did continue to visit the area at least. In November, 1911, he is recorded as having visited friends in town in company with Edwin C. Cotton.

Illustrations:

Harry N. Atwood at the controls of his Burgess-Wright model plane, Bain News Service, publisher, photograph, between 1910-15 (Library of Congress).

Designed by Marblehead, Massachusetts, yacht builder W. Starling Burgess and manufactured by the Wright Company, the Burgess-Wright plane featured a 35 h. p. engine and was capable of flying up to 40 m. p. h.

New York American, "Atwood Flies to New York from Boston", July 2, 1911 (Library of Congress).

The New York newspaper trumpeted Atwood's achievement in flying from Boston to New York, the longest "cross country" flight to date. The flight was also marked the first appearance of an airplane over either Middleborough or Lakeville. Romaine erroneously gives the date of the flight over Middleborough as June 28.

Harry N. Atwood, Grant Park, Chicago, photograph, August, 1911 (Library of Congress).

Atwood is seen during a stopover in Chicago on his record-breaking flight between St. Louis and New York. The flurry of activity surrounding the plane is indicative of the excitement created wherever Atwood appeared with his plane.

Harry N. Atwood in Flight, Bain News Service, publisher, photograph, between 1910-15 (Library of Congress).

Harry N. Atwood in Flight, Bain News Service, publisher, photograph, 1910-15 (Library of Congress).

Harry N. Atwood in his Burgess-Wright model plane, Fall Brook Farm, Middleborough, MA, October 18, 1911, photographic halftone

Atwood posed for this commemorative photograph along with the promoters of the 1911 Middleborough air meet.

Sources:

Brockton Daily Enterprise, "Seen in Middleboro", June 30, 1911; "Middleboro", October 7, 1911; "Atwood Day Aviation Meet", October 11, 1911; "Middleboro", October 14, 1911, and October 17, 1911; "Flies His Kinfolk", October 19, 1911; "Carried Passengers", October 20, 1911; "Middleboro", October 21, 1911, and October 29, 1911; "Shipped to Atwood", November 5, 1911; September, 1952.

Mansfield, Howard. Skylark: The Life, Lies, and Inventions of Harry Atwood. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1999.

New York Times, "Flies 135 Miles with a Passenger", July 1, 1911, and "Fast Flight by Atwood", October 16, 1911.

Romaine, Mertie E. History of the Town of Middleboro, Massachusetts. Volume II. Middleborough, MA: Town of Middleborough, 1969.

“Harry Atwood’s going to fly here” was the phrase that drew the throng

And the speeches went neglected and the speakers were forlorn

For the mighty Harry Atwood was “a tooting’ of his horn.”

Harry Atwood’s going to fly here” was the Shout along the way –

Washington Post, “Atwood Will Not Fly Today”, 1911

Though the Wright Brothers may have achieved manned flight in 1903, the first decade of aviation in America remained inconsistent and seemingly directionless. Stunt-performing exhibition pilots competed with more serious aviators who sought to perfect the art of flying and push the boundaries of the science in order to demonstrate the capabilities of the airplane. Flights were brief and were limited in distance, and were intended primarily to demonstrate a pilot’s skill or to help perfect the design of a particular plane. Flights were also limited in geographic scope, so consequently, when local residents caught their first glimpse of an airplane in flight in late June, 1911, they were understandably enthralled, with all eyes turned naturally to the sky that morning.

Helping promote early aviation locally was native New Englander Harry N. Atwood (1884-1967) who in time developed a large local following in southeastern Massachusetts thanks to family connections in the area (his grandfather Marcus Atwood was a Carver resident). In May, 1911, Atwood enrolled in the Wright Brothers’ flying school at Huffman Prairie outside Dayton, Ohio, where training was rudimentary and consisted of exercises preparatory to brief flights into the air. “After two weeks of training, talking and flying, Harry Atwood graduated. He had completed eighteen lessons and flown for a total of one hour and fifty-five minutes … and in a few weeks he would be a hero.”

Helping promote early aviation locally was native New Englander Harry N. Atwood (1884-1967) who in time developed a large local following in southeastern Massachusetts thanks to family connections in the area (his grandfather Marcus Atwood was a Carver resident). In May, 1911, Atwood enrolled in the Wright Brothers’ flying school at Huffman Prairie outside Dayton, Ohio, where training was rudimentary and consisted of exercises preparatory to brief flights into the air. “After two weeks of training, talking and flying, Harry Atwood graduated. He had completed eighteen lessons and flown for a total of one hour and fifty-five minutes … and in a few weeks he would be a hero.”In a few weeks, in fact, Atwood became the first pilot to fly over Middleborough and Lakeville when on June 30, 1911, he piloted his plane over the two towns enroute to Fall River and ultimately New London where he proposed viewing the Harvard-Yale crew races. Atwood would later continue from Connecticut to New York City in the process establishing a record for the longest "cross country" flight up to that time. Despite this achievement, it was their first glimpse of an airplane that Middleborough and Lakeville residents found noteworthy.

Those who had their eyes to the sky this morning saw aviator Atwood, who went through here at 7:40, headed south. He was reported out of Bridgewater about 7:30, headed for Middleboro.

Those who had their eyes to the sky this morning saw aviator Atwood, who went through here at 7:40, headed south. He was reported out of Bridgewater about 7:30, headed for Middleboro.The aeroplane first appeared in the north about 7:35, and it was probably from 600 to 1000 feet in the air. It was making its way, at a good speed, though apparently without effort. The machine passed to the westward of the town, and was observed by many passengers on the trolley cars which arrive here about 8 a. m., as well as by others.

It was also seen at the state sanatorium in Lakeville, where it apparently came close to the ground, and then swooped off over Lake Assawampsett and Long pond, apparently headed for New Bedford.

Atwood’s biographer writes that as the plane flew overhead, “a small boy was the first to see Atwood, and shouted, ‘See the big bird!’ Atwood could hear the applause below.”

Atwood, that summer, would achieve far wider acclaim by becoming the first pilot to land upon the White House lawn (July 14, 1911) and by piloting a record-breaking flight between St. Louis to New York (August 14-25, 1911). On September 3, Atwood was guest of honor at a reception at the King Philip Tavern at Lakeville and he was still at the height of his fame nationally when he appeared on Friday, October 18, 1911, at an air meet in Middleborough.

For some time, Atwood had been looking for a suitable opportunity to display his aviation skills to his relatives, including his grandfather. In October, 1911, Atwood was engaged for a performance at the Brockton Fair, and he believed that timing would be ideal for a demonstration for his family. Two stories survive giving differing views on how Atwood settled upon Middleborough as the locale for his exploit. One relates that Atwood’s manager, Thomas McLaughlin, “a Boston newspaper man”, contacted James H. Creedon of Middleborough who also worked as a journalist and may have been known to McLaughlin. A different tale relates that Atwood, his performance at Brockton having been cancelled on October 5, traveled to Middleborough to visit with his cousin, pharmacist Kenneth L. Childs who proposed the meet. Regardless of which version is correct, Creedon, Childs and Harlas Cushman of Miller Street worked to promote a meet at Middleborough.

In order to prepare for the meet, Atwood toured the countryside about Middleborough, in search of a suitable makeshift landing field. Ultimately, he settled upon Fall Brook Farm, located at the intersection of Wareham and Grove Streets which featured a large, level, cleared field stretching between Wareham and Tispaquin Streets. At the time, the farm was operated as an automobile inn and the proprietor no doubt saw the meet as a means of attracting business.

In order to prepare for the meet, Atwood toured the countryside about Middleborough, in search of a suitable makeshift landing field. Ultimately, he settled upon Fall Brook Farm, located at the intersection of Wareham and Grove Streets which featured a large, level, cleared field stretching between Wareham and Tispaquin Streets. At the time, the farm was operated as an automobile inn and the proprietor no doubt saw the meet as a means of attracting business.Creedon was named secretary of a committee including Childs, McLaughlin and Edwin C. Cotton of Lynn which promoted the meet, and a number of dignitarires were expected including Governor Eugene N. Foss and Lieutenant Governor Frothingham. Creedon obtained assurances from Atwood’s relatives that they would be present in large numbers, and the town of Carver moved to “make the day a holiday and everyone will head for Middleboro.” The proposed meet generated enormous enthusiasm in town and elsewhere. “The affair was publicized over Cape Cod and through Plymouth county, and considerable interest developed.” Factories and schools made plans to close for the afternoon in order that workers and students would be free to attend. Atwood, himself, helped promote the event, traveling to Carver to visit his grandfather in “a big auto for the time, with wheels which measured 40 inches across and which were almost up to the top of the open body on the car.”

Besides visiting relatives, Atwood spent time preparing his biplane, a Burgess-Wright model, for the meet. Some days before the meet, “a back-firing of the engine broke both propellers and this damage had to be remedied here.” On Sunday, October 13, Atwood gave a few short exhibition flights, and on either the 13th or 14th he took a longer flight to New Bedford accompanied by Edwin C. Cotton. Although the New York Times reported on October 16 that Atwood's flight from New Bedford to Middleborough took only twenty minutes, other sources reported that on the return flight, Atwood had broken the flight, landing in a large field in the vicinity of one of the Quitticas ponds in Lakeville in order to make adjustments. The advent of the temporarily grounded plane was a novelty and not surprisingly created a stir.

Besides visiting relatives, Atwood spent time preparing his biplane, a Burgess-Wright model, for the meet. Some days before the meet, “a back-firing of the engine broke both propellers and this damage had to be remedied here.” On Sunday, October 13, Atwood gave a few short exhibition flights, and on either the 13th or 14th he took a longer flight to New Bedford accompanied by Edwin C. Cotton. Although the New York Times reported on October 16 that Atwood's flight from New Bedford to Middleborough took only twenty minutes, other sources reported that on the return flight, Atwood had broken the flight, landing in a large field in the vicinity of one of the Quitticas ponds in Lakeville in order to make adjustments. The advent of the temporarily grounded plane was a novelty and not surprisingly created a stir.The place where he had landed the machine was two miles from the Middleboro-New Bedford trolley line, but that did not faze some 2000 persons who flocked to the field to get a look at it. They had to walk in some distance from the highway to get their look during the day it was there.

Later, Atwood “took to the air and an old time account relates he made a perfect flight and remained in the air about 12 minutes.” Three days later, on the 16th, Atwood was in New York securing “a new motor and propellers … should their use be necessary.” And while early reports of the meet indicated that Atwood would “instruct a few pupils here in the days before and after the meeting,” it’s not clear whether he did so. One eager would-be aviator, however, C. E. Jenney of Indianapolis who was summering nearby approached Atwood at his Middleborough hotel and requested to be taken on as a student.

Weather conditions on the day of the meet proved unfavorable, with wind and rain, and though a crowd was present, attendance was estimated at only 400 spectators. Atwood delayed his flights in hopes that the weather would abate. Not only the wind, but the rain posed potential problems for a fabric-winged plane. (In 1911 at the Dominguez Field exhibition at Los Angeles, a Burgess-Wright plane flown by Howard Gill would crash during a storm after the fabric of the plane had become so saturated with rain that the extra weight brought the airplane down). “This wait didn’t bother anyone, as they had a chance to view the crude single engined craft, with a kitchen chair for the pilot’s seat; with bed sheeting covering the wings of the biplane to sustain flight. The struts were of wood, and a ‘stick’ was the instrument for raising and lowering it, while another one aided in handling its turns and side motion.”

Weather conditions on the day of the meet proved unfavorable, with wind and rain, and though a crowd was present, attendance was estimated at only 400 spectators. Atwood delayed his flights in hopes that the weather would abate. Not only the wind, but the rain posed potential problems for a fabric-winged plane. (In 1911 at the Dominguez Field exhibition at Los Angeles, a Burgess-Wright plane flown by Howard Gill would crash during a storm after the fabric of the plane had become so saturated with rain that the extra weight brought the airplane down). “This wait didn’t bother anyone, as they had a chance to view the crude single engined craft, with a kitchen chair for the pilot’s seat; with bed sheeting covering the wings of the biplane to sustain flight. The struts were of wood, and a ‘stick’ was the instrument for raising and lowering it, while another one aided in handling its turns and side motion.”Eventually, the wind stilled enough for Atwood to attempt a flight, and he would ultimately complete three flights that day. During the first flight, Atwood circled the field at Fall Brook before flying over Tispaquin Pond, and then returning to the field. It was probably on this flight that

he ran into a heavy rain shower, which continued several minutes. He said when he alighted that the rain drops struck his face like bullets. He did some skillful work in fancy flying which thrilled the crowd. He found the air dangerous, however, and somewhat squally.

For the subsequent two flights, Atwood invited a passenger along on each. Mrs. Edwin C. Cotton accompanied Atwood on his second flight of five minutes for what was her first time in the air. Completely exhilarated by the experience, she informed reporters that “it was perfectly delightful, and I don’t ever remember of enjoying anything so much.” Atwood’s second passenger that afternoon was his chauffeur, Leo Malanson.

Following Atwood’s performance, his plane was left behind at Fall Brook Farm where it was “drawn up behind a barn and lashed to the ground,” likely attracting the curious. Later, “a representative of the factory” arrived in town to disassemble the plane which finally, on November 4, was shipped from Middleborough. While Atwood never again flew at Middleborough, he did continue to visit the area at least. In November, 1911, he is recorded as having visited friends in town in company with Edwin C. Cotton.

Following Atwood’s performance, his plane was left behind at Fall Brook Farm where it was “drawn up behind a barn and lashed to the ground,” likely attracting the curious. Later, “a representative of the factory” arrived in town to disassemble the plane which finally, on November 4, was shipped from Middleborough. While Atwood never again flew at Middleborough, he did continue to visit the area at least. In November, 1911, he is recorded as having visited friends in town in company with Edwin C. Cotton.Illustrations:

Harry N. Atwood at the controls of his Burgess-Wright model plane, Bain News Service, publisher, photograph, between 1910-15 (Library of Congress).

Designed by Marblehead, Massachusetts, yacht builder W. Starling Burgess and manufactured by the Wright Company, the Burgess-Wright plane featured a 35 h. p. engine and was capable of flying up to 40 m. p. h.

New York American, "Atwood Flies to New York from Boston", July 2, 1911 (Library of Congress).

The New York newspaper trumpeted Atwood's achievement in flying from Boston to New York, the longest "cross country" flight to date. The flight was also marked the first appearance of an airplane over either Middleborough or Lakeville. Romaine erroneously gives the date of the flight over Middleborough as June 28.

Harry N. Atwood, Grant Park, Chicago, photograph, August, 1911 (Library of Congress).

Atwood is seen during a stopover in Chicago on his record-breaking flight between St. Louis and New York. The flurry of activity surrounding the plane is indicative of the excitement created wherever Atwood appeared with his plane.

Harry N. Atwood in Flight, Bain News Service, publisher, photograph, between 1910-15 (Library of Congress).

Harry N. Atwood in Flight, Bain News Service, publisher, photograph, 1910-15 (Library of Congress).

Harry N. Atwood in his Burgess-Wright model plane, Fall Brook Farm, Middleborough, MA, October 18, 1911, photographic halftone

Atwood posed for this commemorative photograph along with the promoters of the 1911 Middleborough air meet.

Sources:

Brockton Daily Enterprise, "Seen in Middleboro", June 30, 1911; "Middleboro", October 7, 1911; "Atwood Day Aviation Meet", October 11, 1911; "Middleboro", October 14, 1911, and October 17, 1911; "Flies His Kinfolk", October 19, 1911; "Carried Passengers", October 20, 1911; "Middleboro", October 21, 1911, and October 29, 1911; "Shipped to Atwood", November 5, 1911; September, 1952.

Mansfield, Howard. Skylark: The Life, Lies, and Inventions of Harry Atwood. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1999.

New York Times, "Flies 135 Miles with a Passenger", July 1, 1911, and "Fast Flight by Atwood", October 16, 1911.

Romaine, Mertie E. History of the Town of Middleboro, Massachusetts. Volume II. Middleborough, MA: Town of Middleborough, 1969.

Sunday, June 21, 2009

Middleborough's "Red Scare", 1919-20

Before the days when McCarthyism sent Americans scurrying to check underneath their beds for Communists, America experienced its first "red scare" in 1919, in the wake of an aborted attempt by presumed alien radicals to mail 36 bombs to various American men of prominence and power, sychronized to detonate, appropriately enough, on May Day, 1919. Fueled by the apparent success of the Russian Revolution and the dramatic increase in immigration from Eastern Europe to this country, the fears of many Americans were that a similar revolution could occur here, and they were whipped into an anti-Communist frenzy led by U. S. Attorney General (and intended bombing target) A. Mitchell Palmer. A general strike in Seattle, the police strike in Boston, a major steel strike which saw martial law implemented in Gary, Indiana, and numerous race riots throughout the nation exacerbated growing fears of industrial and political unrest during early and mid-1919.

Despite May Day bombings at Boston and Newtonville which did bring the scare closer to Middleborough, the town remained free of any direct Communist agitation until October 1919.

Despite May Day bombings at Boston and Newtonville which did bring the scare closer to Middleborough, the town remained free of any direct Communist agitation until October 1919.

While the Middleborough Nest, No. 1824, Order of Owls (or O. O. O.), a local fraternal organization certainly did not have a history of inviting Communist agitators to the community, that is precisely what it did when it lent its hall to two unnamed Middleborough men for what was to have been a "socialist rally" on October 28. The rally, in fact, was a Communist Party rally headed by John J. Ballam, the acknowledged leader of the Massachusetts Communists, and editor of the Worker, a Communist paper published twice a month at Boston.

Ballam, at the time of the Middleborough meeting, had only recently been released from a one-year stint in the Plymouth County House of Correction for violation of the Espionage Act. Just weeks prior to the Middleborough rally, Ballam had attended the first convention of the Communist Party of America in Chicago where Ballam acted as chairman on the sixth day.

At Middleborough, Ballam "gave expression to the most radical statements ever heard in this vicinity," stressing the importance of "Force and Revolution." Following "slurring talk of 'You Americans,' 'Your Religion,' etc.," Ballam "scored the American government in regular Bolshevik terms" and "told the audience that if they wanted any of the lands about them they were theirs; they should seize them and he advocated using force to hold the property if necessary." Ballam, himself, considered his Middleborough speech as going far beyond his previous forays in Communist incendiarianism. He "said that he had served a year in jail for his utterances and on occasion he had never said one-half as much as he had this evening."

What possessed Ballam to believe that Middleborough was ripe for socialist revolution is unfathomable as it was a staunchly conservative community. Though active locally, labor unions were not particularly strong, or excessively adversarial, and they were even sometimes suspect for their generally warm relations with management.

Ballam's appeal at the October, 1919, rally seems to have been directed towards newly-arrived immigrants in the community, yet it met with little response. Like residents elsewhere, Middleborough residents were too caught up in national differences to notice any grievious social or economic inequities which may have existed. In 1897, ten Armenians had walked out of Leonard & Barrows' shoe manufactory not because of economic or social inequities, but because the firm had hired a Turk whom the Armenians suspected of being an Ottoman agent. Nearly a quarter of a century later, these divisive attitudes lingered among the various nationalities locally, and could still prove the foil of international social revolution.

Ballam's appeal at the October, 1919, rally seems to have been directed towards newly-arrived immigrants in the community, yet it met with little response. Like residents elsewhere, Middleborough residents were too caught up in national differences to notice any grievious social or economic inequities which may have existed. In 1897, ten Armenians had walked out of Leonard & Barrows' shoe manufactory not because of economic or social inequities, but because the firm had hired a Turk whom the Armenians suspected of being an Ottoman agent. Nearly a quarter of a century later, these divisive attitudes lingered among the various nationalities locally, and could still prove the foil of international social revolution.

Ballam achieved little result for his efforts at Middleborough other than, undoubtedly, embarrasssing the Owls. He was arrested a month and a half later at New Orleans on board the steamship Mexico bound for Mexico, on an indictment by the Suffolk County Grand Jury charging him with making incendiary speeches and "advocating Bolshevism and Communism."

Middleborough was little troubled by the event, and the Gazette's coverage of the whole incident was simply and mildly headlined: "Some Radical Talk."

The following May, 1920, a second attempt to incite the populace was attempted by two unknown men who began anonymously distributing Communist circulars throughout town, but again with minimal success. The circulars, headed "Hail to the Soviets - May Day Proclamation by the Central Executive Committee of the Communist Party in America" apparently contained a rant similar to the one provided by Ballam several months earlier, calling for a cessation of work on May Day "as a demand for the release of industrial and political prisoners and as a demonstration of the power of the workers." Again, the community took little notice of the propaganda, other than curiosity, and notice of the item was not even deemed newsworthy enough for the front pages locally.

With these two salvos, Communist attempts to incite the local population to revolution in 1919-20 failed dismally. Confident and comfortable in its conservatism, and secure in the knowledge that ideas such as Ballam's held no appeal to the mass of local residents, Middleborough was able to avoid the worst excesses of America's initial "Red Scare."

Despite May Day bombings at Boston and Newtonville which did bring the scare closer to Middleborough, the town remained free of any direct Communist agitation until October 1919.

Despite May Day bombings at Boston and Newtonville which did bring the scare closer to Middleborough, the town remained free of any direct Communist agitation until October 1919.While the Middleborough Nest, No. 1824, Order of Owls (or O. O. O.), a local fraternal organization certainly did not have a history of inviting Communist agitators to the community, that is precisely what it did when it lent its hall to two unnamed Middleborough men for what was to have been a "socialist rally" on October 28. The rally, in fact, was a Communist Party rally headed by John J. Ballam, the acknowledged leader of the Massachusetts Communists, and editor of the Worker, a Communist paper published twice a month at Boston.