Showing posts with label industry. Show all posts

Showing posts with label industry. Show all posts

Friday, December 17, 2010

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington Operatives

At its peak, Hathaway, Soule & Harrington’s Middleborough branch is said to have employed about 200 operatives. While no definitive records exist detailing exactly who was employed in the plant, town directories for 1895, 1897 and 1899, combined with the federal census record of 1900, are useful in creating a partial list of operatives during the final years of the branch plant’s operation, as well as the roles which they occupied within the factory.

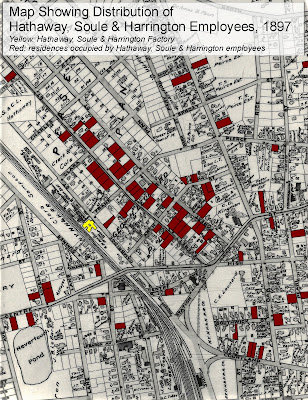

Not surprisingly, given their lack of transportation, most operatives of Hathaway, Soule & Harrington needed to live close by the factory. The presence of the plant provided impetus for the residential growth of the district north of Everett Square and east of Cambridge Street during the last two decades of the nineteenth century. By the mid-1890s, certain streets within the district had become closely wedded to the plant. Most notable was Everett Street itself where one out of every two households had a member employed by the firm. Frequently, more than one family member was employed by the firm, a circumstance which further strengthened the connection between industry and community within the neighborhood.

The rapid growth of a residential neighborhood, in turn, promoted commercial development within the district. The Spooner Block on the northeast corner of Everett and Arch Streets was constructed at this time and the inclusion of a grocery on its first floor provided nearby residents with a store within walking distance. Still other businesses were established around Everett Square at what was then known as Middleborough’s West End (in distinction to the West Side on the opposite side of the railroad line). These developments created a closely knit community where residents not only lived and shopped together, but worked closely together, as well.

There are no known records detailing the closure of Hathaway, Soule & Harrington’s Middleborough plant, but it is likely to have been both financially and emotionally devastating at the time, given the dependence much of the neighborhood had upon the firm for its livelihood. Though HS&H offered its Middleborough operatives positions in the New Bedford plant it seems that few accepted. Among them was Wilkes H. F. Pettee, the engineer of the Middleborough plant, who temporarily joined Hathaway, Soule & Harrington at New Bedford before returning to Middleborough in 1906 when he took a position with the George E. Keith Company which opened a local branch in that year. Most former Hathaway, Soule & Harrington operatives however remained at Middleborough where they were likely absorbed into the workforces of Alden, Walker & Wilde which opened in 1900; Leonard & Barrows which was expanding its workforce at the time; and Leonard, Shaw & Dean. Additionally Brockton remained an alternative for many and several former Hathaway, Soule & Harrington operatives relocated to that city where the larger number of shoe manufactories promised greater opportunity and seemingly better job security.

List of Middleborough Residents Employed by Hathaway, Soule & Harrington

1895

Names and addresses are taken from Resident and Business Directory of Middleboro and Lakeville, Mass. (Needham, MA: A. E. Foss & Co., 1895). Occupations are noted where listed in the directory. Boarders are listed as “bds.” followed by the name of the person with whom they boarded (which in most cases was a parent).

Andrew Alden, superintendent, 149 Center

Arthur H. Alden, foreman stitching room, 64 Everett

J. Gardner Alden, 42 Forest

George E. Aldrich, 73 Everett

Eunice A. Allen, bds. Nathaniel L. Allen 6 Elm

Charles E. Ashley, 45 Vine

George Henry Bailey, bds. George Bailey 10 Myrtle

Harry Banwell, 12 Arch

Ella F. Baker, bds. Marcus M. Thompson 7 Everett

Earl G. Besse, Jr., East Main

Isaac P. Breach, 13 Everett

William E. Bryant, Plymouth

Andrew P. Bunker, 78 Everett

Luke Callan, 11 Clifford

Luke F. Callan, bds. Luke Callan 11 Clifford

Herbert L. Caswell, 67 Cambridge

S. H. Caswell, 56 Vine

Henry H. Chace, 18 Pearl

William B. Chandler, 55 Everett

William F. Chandler, bds. William B. Chandler 55 Everett

Nellie M. Chickering, bds. Edgar W. Tinkham 61 Everett

Will L. Chipman, 5 West

David R. Clark, overseer, 4 Forest

John M. Conant, bds. Isaac Shaw 15 Everett

Walter A. Coombs, 12 Southwick

Charles H. Crandall, night watchman, 9 Lane

John H. Cronan, bds. Andrew Cronan 67 Vine

Asa F. Crosby, Jr., bds. Asa F. Crosby 10 West

Joseph H. Crosby, bds. Asa F. Crosby 10 West

Carrie Cudworth, bds. Mrs. Annie Lloyd 18 Southwick

William Curran bds. Mrs. Hannah Stevens 41 Forest

Messup David, 9 Cottage Court

Flora M. De Maranville, bds. Mrs. Eliza J. De Maranville 270 Center

Nellie F. De Maranville, bds. Mrs. Eliza J. De Maranville 270 Center

James Dorigan, bds. Cornelius Dorigan 55 Vine

Gertrude Drew, bds. William H. Downey 147 Center

Ellis D. Dunham, 27 Elm

Henry A. Eaton, 53 Everett

George Egger, 15 Arch

Philip L. Egger, bds. Philip Egger Plymouth Street

Charles A. Englestad, 238 Center

Walter Farmer, bds. Thomas A. Churbuck 44 Forest

Leon B. Farrington, 18 Everett

J. Emma Finney, bds. Mrs. Isabel H. Finney 131 Center

George Fosberg, bds. Charles F. Fosberg 19 East Main

Ansel Fuller, 10 Webster

Charles F. Fuller, bds. Albert S. Sparrow 2 Lincoln

Herman W. Fuller, bds. Ansel Fuller 10 Webster

Frank Gardner, bds. Mrs. Hannah Stevens 41 Forest

William H. Goodwin, 77 North Main

Leonard W. Gurney, bds. James L. Gurney 10 Arch

Wilson T. Harlow, bds. Mrs. Lucinda A. Harlow 33 Courtland

Eugene Hathaway, bds. Mrs. Ella E. Estes 12 Frank

Israel T. Hathaway, 13 North

Samuel Hathaway, 29 Courtland

Alvin Hayward, bds. Albert S. Sparrow 2 Lincoln

Arthur A. Holmes, bds. Theodore P. Holmes Grove

W. Frank Holmes, bds. Albert H. Merrihew 10 West

William F. Holmes, bds. Theodore P. Holmes Grove

Waldo E. Jackson, bds. Mrs. Clara Jackson 200 Center

Mabel E. Jefferson, bds. James M. Jefferson 15 West

August P. Johnson, bds. John M. Johnson 70 Forest

George H. Keedwell, 79 Water

Saul Labonte, bds. Mrs. Ella E. Estes 12 Frank

George Henry Lakey, bds. Rodney I. Ellis [boarding house] 104 Center

Mattie C. Landers, bds. William Lumberd 5 Southwick

James E. Leggee, bds. Henry J. Leggee 6 Lovell

Orville N. Leonard, 16 Arch

John L. Luippold, bds. John M. Luippold 17 Arch

Lizzie A. Luippold, bds. John M. Luippold 17 Arch

Charles A. Mabry, 23 Elm

Mary A. Maker, bds. M. Jennie Francis, 54 Everett

Edgar Mason, bds. Rufus J. Brett 14 Forest

Eugene H. McCarthy, 171 Center

Mrs. L. F. McFarland, 85 Forest

Oliver Nichols, 65 Oak

Robert E. Nolan, bds. William Nolan 28 Montello

James J. O’Hara, laster, 48 Vine

Fred A. Orcutt, bds. J. Carter

George Perkins, bds. Mrs. B. F. Johnson [private boarding house] 19 South Main

George A. Perkins, foreman packing-room, boards Mrs. B. F. Johnson [private boarding house] 19 South Main

Hannah M. Perry, bds. Mrs. Narcissa A. Perry Plymouth

Mary L. Perry, bds. Mrs. Narcissa A. Perry Plymouth

Arthur W. Petersen, bds. Rodney I. Ellis [boarding house] 104 Center

Maggie E. Plunkett, bds. Peter Plunkett 49 Vine

Mary A. Plunkett, bds. Peter Plunkett 49 Vine

Emily M. Pratt, bds. Silas Pratt 6 Barrows

William B. Rafuse, 9 Courtland

Myron F. Raymond, bds. Marcus M. Raymond 3 Lincoln

Robert N. Raymond, 73 Everett

Esther Rees, bds. 66 Everett

S. Everett Ryder, Plymouth near the Green

Alfred A. Shaw, stitcher, 41 School

C. Henry Shaw, 22 Pearl

Elmer F. Shaw, 32 Arch

Lewis W. Shaw, 156 Center

Marcus A. Shaw, bds. Samuel Shaw

May F. Shaw, bds. Frank H. Shaw 56 School

Alice Shay, bds. Asa C. Bennett 12 Arch

Lucy Sheehan, bds. Thomas B. Sheehan 16 East Main

Mary Sheehan, East Main

John L. Shepherd, 152 Center

Katie M. Sherman [Shuman], bds. Arthur H. Alden 64 Everett

Mamie F. Sherman [Shuman] bds. Arthur H. Alden 64 Everett

Wilford Shuman, bds. Arthur H. Alden 64 Everett

C. Alice Shurtleff, bds. Virgil W. Shurtleff 11 Lovell

Joseph B. Simmons 30 School

Annie Smith, bds. Mrs. Annie Lloyd 18 Southwick

L. M. Smith, bds. Wilkes H. F. Pettee 59 Everett

Martin Smith, 13 Rock

Fred Southwick, 23 Arch

Harry Staples, bds. Thomas A. Churbuck 44 Forest

John J. Sullivan, 229 Center

Mrs. Mary J. Sullivan, 174 Center

John H. Swift, 62 Forest

Henrietta D. Taylor, bds. Mrs. Elizabeth Taylor 91 Oak

Marcus M. Thompson, 7 Everett

William W. Tinkham, bds. B. Frank Tinkham 75 Oak

Clifford L. Vaughan, bds Mrs. Helen F. Vaughan 9 Oak

Foster Wade, bds. Ezekiel H. Aldrich 14 Barrows

Nelson C. White, 57 Everett

William H. Wilde, supt., bds. Mrs. Frances Wilde 34 Pearl

Thomas E. Wilmot, 16 Everett

Kenelm Winslow, 14 Pearl

1897

Names and addresses are taken from Resident and Business Directory of Middleboro, Massachusetts: For 1897 (Needham, MA: A. E. Foss & Co., 1897). Occupations are noted where listed in the directory. Boarders are listed as “bds.” followed by the name of the person with whom they boarded (which in most cases was a parent).

Andrew Alden, superintendent, 24 Forest

Arthur H. Alden, foreman stitching room, 64 Everett

J. Gardner Alden, 42 Forest

Eldon L. Aldrich, bds. Ira F. Aldrich Arlington

George E. Aldrich, 73 Everett

Ira F. Aldrich, Arlington

Eunice A. Allen, boards Nathaniel L. Allen 68 Forest

Obed D. Allen, bds. Nathaniel L. Allen 68 Forest

Charles E. Ashley, laster, 269 Center

Charles Bagamian, bds. 62 Arch

Harry Bagamian, 62 Arch

Harry Banwell, bds. 12 Arch

Ella F. Barker, bds. M. M. Thompson 7 Everett

James P. Bolton, stitcher 63 Everett

Edward Bonney, 105 South Main

Charles Borden, bds. 287 Center

Ezra J. Bourne, cutter 35 Courtland

Ella F. Bowker, bds. 7 Everett

William E. Bryant, Plymouth

Andrew P. Bunker, 78 Everett

Luke Callan, 11 Clifford

Luke F. Callan, bds. Luke Callan 11 Clifford

Mary Casey, stitcher, bds. Hannah Casey 13 Montello

Mary E. Casey, bds. 13 Montello

Annie A. Chace, bds. 88 Oak

Henry H. Chace, 18 Pearl

William B. Chandler, 55 Everett

William F. Chandler, bds. W. B. Chandler 55 Everett

Nellie M. Chickering, bds. Edgar W. Tinkham

David R. Clark, overseer, 16 Forest

John M. Conant, bds. 15 Forest

Walter A. Coombs, 12 Southwick

John H. Cronan, bds. Mrs. Ann Cronan 67 Vine

Joseph H. Crosby, bds. 10 West

Messup David, 9 Cottage Court

Flora M. De Maranville, bds. Mrs. Eliza J. De Maranville 270 Center

Nellie F. De Maranville, bds. Mrs. Eliza J. De Maranville 270 Center

Katie Doherty, bds. Neal Doherty 22 Everett

Mary J. Doherty, bds. Neal Doherty 22 Everett

James Dorigan, bds. 55 Vine

Gertrude Drew, bds. W. H. Downing 49 Everett

Ellis D. Dunham, 27 Elm

George A. Earle, 66 Everett

Emma A. Eaton, bds. Henry A. Eaton 53 Everett

Francis R. Eaton, leather cutter, 14 Rock

Henry A. Eaton, 53 Everett

Nellie F. Eaton, bds. Henry A. Eaton 53 Everett

George Egger, 15 Arch

Philip L. Egger, bds. Philip Egger Plymouth

James A. F. Elliot, bds. Lillian B. Elliot 63 Water

Charles A. Englested, 238 Center

Henry A. Farrington, 5 Southwick

Leon B. Farrington, 18 Everett

J. Emma Finney, bds. Mrs. Isabel H. Finney 77 Everett

George Forsberg, bds. Charles F. Forsberg 19 East Main

Emma L. Francis, 54 Everett

Ansel Fuller, 10 Webster

Herman W. Fuller, bds. Ansel Fuller 10 Webster

Stephen S. Gibbs, 17 Everett

William H. Goodwin, 17 Pearl

Annie Gurney, bds. James L. Gurney 10 Arch

Leonard W. Gurney, bds. James L. Gurney 10 Arch

Wilson T. Harlow, bds. Mrs. Lucinda A. Harlow 33 Courtland

Samuel Hathaway, 29 Courtland

Alvin Hayward, bds. Albert S. Sparrow 62 Everett

Maria D. Herman, bds. George H. Herman 244 Center

Elmer E. Holmes, bds. Theodore P. Holmes Grove

William F. Holmes, 15 Oak

Charles Horton, 66 Everett

Waldo E. Jackson, bds. Mrs. Clara Jackson 200 Center

August P. Johnson, bds. John M. Johnson 70 Forest

Henry W. Keith, stitcher, 35 Cambridge

Saul Labonte, bds. 117 Center

Mattie L. Landers, bds. 54 Everett

Ferdinand Landgrebe, North

Saul Lebonte, bds. 33 Pearl

Henry J. Leggee, laster, 7 Lovell

James E. Leggee, bds. Henry J. Leggee 7 Lovell

John L. Luippold, bds. John M. Luippold 17 Arch

Lizzie A. Luippold, bds. John M. Luippold 17 Arch

Carrie Mann, bds. 88 Oak

Edward Mason, bds. 14 Forest

Eugene H. McCarthy, 53 Everett

Sampson McFarland, bds. 54 Everett

William A. Merrihew, 23 High

Oliver Nichols, 273 Center

Arthur Nickerson, 15 Everett

Robert E. Nolan, bds. William Nolan 28 Montello

James J. O’Hara, laster, 48 Vine

Fred A. Orcutt, bds. J. Carter Plymouth

Ellen P. Penley, bds. Mrs. Priscilla S. Penley, 68 Everett

Josiah F. Penniman, laster, 23 North

Hannah M. Perry, bds. Mrs. Narcissa A. Perry Plymouth

Mary L. Perry, bds. Mrs Narcissa A. Perry Plymouth

William H. Perry, 12 Elm

Wilkes H. F. Pettee, engineer, 38 Forest St

Willie Phinney, bds. 54 Everett

Mary A. Plunkett, bds. Peter Plunkett 49 Vine

William B. Rafuse, 106 Everett

Frank C. Raymond, laster, 113 South Main

Myron F. Raymond, bds. Marcus M. Raymond Myrtle Avenue

Robert N. Raymond, 73 Everett

Charles W. Ricker, bds. Union House Center

Albert Rogers, bds. 55 Everett

Charles M. Rounds, bds. M. A. Leahy 19 Everett

Herbert H. Ryder, bds. A. F. Ryder 25 North

Sadie P. Ryder, bookkeeper, bds. Mrs. Jane P. Ryder 28 Peirce

Alfred A. Shaw, stitcher, 55 Forest

Lewis W. Shaw, 78 Forest

Marcus A. Shaw, bds. Samuel Shaw 19 Center

May F. Shaw, bds. F. H. Shaw 56 School

Mary Sheehan, 16 East Main

Levi Sherman, 50 Forest

Mary F. Sherman, bds. Levi Sherman 50 Forest

Wilford Shuman, bds. 33 Pearl

C. Alice Shurtleff, bds. Virgil W. Shurtleff 16 Arlington

Fred Southwick, 23 Arch

Harry E. Staples, 71 Everett

John J. Sullivan, 229 Center

Mrs. Mary J. Sullivan, 174 Center

Harry Swift, bds. Mrs. William H. Swift 8 Forest

John H. Swift, 62 Forest

Henrietta D. Taylor, bds. Mrs. Elizabeth Taylor 91 Oak

Marcus M. Thompson, 7 Everett

William W. Tinkham, bds. B. F. Tinkham 75 Oak

Foster Wade, bds. E. H. Aldrich 14 Barrows

Nelson C. White, 57 Everett

William H. Wilde, clerk, 33 Pearl

Thomas E. Wilmot, 16 Everett

1899

Names and addresses are taken from Resident and Business Directory of Middleboro’ and Lakeville, Massachusetts, For 1899. (Needham, MA: A. E. Foss & Co.,1899). Birth dates and occupations are taken from the Federal census taken in June, 1900, two months following the closure of Hathaway, Soule & Harrington. Shoe manufacturing required skilled workers and shoe operatives typically remained within their area of expertise. It therefore may be presumed that the occupation listed for each operative in June, 1900, was the same occupation that worker pursued while employed by Hathaway, Soule & Harrington. Boarders are listed as “bds.” followed by the name of the person with whom they boarded (which in most cases was a parent).

Andrew Alden (b. 1838), foreman, 24 Forest

Arthur H. Alden (b. December 1864), supt., 64 Everett

J. Gardner Alden (b. January 1862), stitcher, 42 Forest

Eldon L. Aldrich (b. January 1878),”sole laying”, bds. Ira F. Aldrich Arlington

He relocated to Brockton with his father, Ira F. Aldrich, and family following the closure of HS&H.

Ira F. Aldrich (b. 1862), laster, Arlington

He relocated to Brockton following the closure of HS&H.

Ervin O. Allen (b. April 1874), finisher, bds. Nathaniel L. Allen 29 School

Eunice A. Allen (b. August 1876), bds. Nathaniel L. Allen 29 School

Obed D. Allen (b. September 1872), treer, 68 Forest

Charles E. Ashley, laster, 254 Center

Harry Banwell (b. March 1863), treer, 54 Pearl

Charles J. Bopp (b. December 1881), burnisher, bds. Mrs. Elizabeth Bopp 92 Oak

Charles Borden (b. December 1879), bds. Charles G. Borden, 72 Water

Following the closure of HS&H he took work as a day laborer.

Mary E. Boucher (b. December 1862), stitcher, bds. Thomas Boucher 144 Center

Ezra J. Bourne, cutter, 35 Courtland

Ella F. Bowker (b. March 1867), stitcher, bds. 7 Everett

The Bowker family removed to Kingston following the closure of HS&H.

Luke Callan (b. September 1837), 11 Clifford

He took work as a day laborer following the closure of HS&H.

Luke F. Callan (b. January 1873), laster, bds. Luke Callan 11 Clifford

H. Percy Caswell (b. June 1867), upper leather cutter, 16 Barrows

Henry H. Chace B. June 1858), upper leather cutter, 18 Pearl

William B. Chandler (b. September 1845), Goodyear sewer, 25 Forest

Alberto F. [Albert W.] Chase, (b. October 1879), shoe worker, bds. Mrs. Clara A. Chase 6 Coombs

Lizzie M. Chase (b. May 1881), shoe worker bds.Mrs. Clara A. Chase 6 Coombs

Nellie M. Chickering (b. June 1867), skiver, bds. Edgar W. Tinkham 61 Everett

Fred F. Churbuck, cutter, 18 Webster

David R. Clark (b. December 1842), overseer, 18 Forest

Harry L. Clark (b. 1874), cutter, bds. Nelson Thomas Tispaquin

Roy C. Coombs (b. September 1878), sole cutter, bds. William A. Coombs 24 East Grove

Walter A. Coombs, 12 Southwick

John H. Cronan (b. December 1869), shoemaker, bds. Mary Cronan 67 Vine

Othello E. Dean (b. November 1865), laster, 22 Pearl

Harry A. De Maranville, 143 South Main

Flora M. De Maranville (b. August 1872), bds. Mrs. Eliza J. De Maranville 270 Center

Nellie F. De Maranville (b. October 1869), shoeworker, bds. Mrs. Eliza J. De Maranville 270 Center

Katie Doherty, bds. Neal Doherty 3 Station

James Dorigan (b. November 1866), shoemaker, 55 Vine

Elmer O. Drew (b. January 1875), “moulding (shoe)”, 11 Barrows

Gertrude I. Drew, bds 10 Elm

Ellis D. Dunham (b. January 1841), trimmer, 27 Elm

Morton W. Dunham (b. June 1878), 285 Center

William L. Dunham (b. October 1869), heeler, 32 Webster

George A. Earle, 66 Everett

Emma A. Eaton (b. August 1874), stitcher, bds. Henry A. Eaton 53 Everett

Francis R. Eaton, leather cutter, 14 Rock

Henry A. Eaton (b. December 1838), heel finisher, 53 Everett

Nellie F. Eaton (b. August 1861), stitcher, bds. Henry A. Eaton 53 Everett

George Egger (b. April 1860), finisher, 15 Arch

Philip L. Egger, bds. Philip Egger Plymouth

Henry A. Farrington (b. September 1864), “tacker on”, 5 Southwick

Leon B. Farrington (b. September 1870), sole leather cutter, 24 West Grove

Emma J. Finney (b. October 1854), skiver, bds. Mrs. Isabel H. Finney 77 Everett

She removed to Brockton with her mother and sister (who was a stitcher) following the closure of HS&H.

George Forsberg, 55 Everett

Emma L. Francis (b. February 1857), vamper, 54 Everett

Nelson T. Frank, bds. 18 Webster

Ansel Fuller (b. September 1834), “shoe tacker”, 10 Webster

Stephen S. Gibbs, 17 Everett

Leonard W. Gurney (b. May 1880), shoe edge setter/sewer, bds. John Harper 33 Webster

Wilson T. Harlow (b. September 1863), edge maker, bds. Mrs. Lucinda A. Harlow 33 Courtland

Julia A. Harrington (b. October 1872), vamper, bds. Mrs. Margaret T. Harrington 22 Everett

Elmer E. Holmes (b. August 1868), finisher, bds. Theodore P. Holmes Grove

William F. Holmes (b. May 1866), heel finisher, 15 Oak

Edward Jenney (b. February 1863), cutter, 13 Everett

August P. Johnson (b. December 1872), cutter, 63 Everett

Henry W. Keith (b. June 1876), stitcher, 35 Cambridge

Warren King, 68 Forest

Saul Labonte (b. October 1867), cutter, 34 Arch

He took a position with HS&H at New Bedford following Middleborough branch closure.

Mattie L. Landers, bds. 54 Everett

Ferdinand C. Landgrebe (b. March 1855), “Scourer (shoe)”, North

Henry J. Leggee (b. November 1860), laster, 7 Lovell

James E. Legee (b. May 1845), “shoemaker”, bds. Henry J. Leggee 7 Lovell

George B. Leonard (b. May 1847), treer, South Main near Lakeville line

John L. Luippold (b. August 1874), bds. John M. Luippold 17 Arch

Lizzie A. E. Luippold (b. December 1859), stitcher, bds. John M. Luippold 17 Arch

Arthur H. Macomber, bds. William H. Macomber 40 West Grove

Barzella W. Macomber (b. January 1879), edge setter, bds William H. Macomber 40 West Grove

Thomas F. Maloney, bds. Mrs. Kelley’s off East Main

Carrie Mann, bds. 3 Maple Ave

Eugene H. McCarthy, 53 Everett

Probably the same Eugene H. McCarthy, “shoemaker”, resident at Brockton in 1900.

Albert E. Metcalf, bds. 18 Webster

Philip E. Morris (b. September 1870), laster, 15 Barrows

Alice L. Murtagh (b. August 1875), packer, bds. Thomas H. Murtagh Cherry

Oliver Nichols (b. December 1866), “shoemaker”, 273 Center

Frederick A. O’Brien, bds. Francis Warren 107 Everett

Fred A. Orcutt, 27 Lovell

Myron E. Orcutt (b. March 1880), bds. Walter F. Orcutt Plymouth

Following the closure of HS&H, he went to work as a far laborer for poultry dealer George Morse of Plymouth Street

Ellen P. Penley (b. May 1863), “shoeworker”, bds. Mrs. Priscilla S. Penley 200 Center

Ella A. Perry (b. September 1868), bds. Mrs. Narcissa A. Perry Plymouth

Hannah M. Perry (b. August 1870), bds. Mrs. Narcissa A. Perry Plymouth

Mary L. Perry, bds. Mrs. Narcissa A. Perry Plymouth

Wilkes H. F. Pettee (b. July 1846), stationary engineer, 38 Forest

He accepted HS&H’s offer of a position in the New Bedford factory and was employed by them there until 1906 when he returned to Middleborough to enter the employ of the George E. Keith Company which opened a massive shoe manufactory on Sumner Avenue that year.

Mary A. Plunkett (b. August 1874), bds. Peter Plunkett 49 Vine

Michael Quinn, shipper, 23 West

Frank C. Raymond (b. September 1865), laster, Cottage Court

Marcus Raymond (b. August 1876), upper leather cutter, bds. Marcus M. Raymond Myrtle Avenue

Myron F. Raymond (b. March 1872), sole leather cutter, bds. Marcus M. Raymond Myrtle Avenue

Robert N. Raymond, Keith

James H. Rogers, bds. 32 West Grove

Sarah P. K. Ryder, bookkeeper, bds. Mrs. Jane P. Ryder 28 Peirce

Abbie Z. Shaw (b. March 1876), stamper, bds. 21 Arch

Alfred A. Shaw (b. May 1872), stitcher 61 Forest

He was working as a salesman following the closure of HS&H.

C. Henry Shaw, Frank

Elmer E. Shaw (b. April 1862), laster, 79 Everett

Lewis W. Shaw (b. June 1860), 78 Forest

Mary F. Sheehan (b. December 1866), stitcher, 16 East Main

Levi Sherman (b. March 1845), fan stitcher, 50 Forest

Mary F. Sherman, bds. Levi Sherman 50 Forest

Carrie Shuman, bds. Levi Sherman 50 Forest

Wilford Shuman, bds. 32 Pearl

George D. Simmons (b. December 1875), treer, bds. 18 Everett

Clarence E. Smith, bds. Mrs. Mary A. Smith Fuller

Harry E. Staples, 71 Everett

John J. Sullivan (b. April 1870), 229 Center

The closure of HS&H prompted Sullivan to find a new career as a newsdealer. He would later operate a noted news stand near the Four Corners for many years.

Mrs. Mary J. Sullivan (b. September 1861), stitcher, 174 Center

Nora Sullivan (b. September 1861), “shoemaker”, bds. John J. Sullivan 229 Center

Arthur L. Thomas (b. November 1865), laster, 15 Barrows

Henry L. Thomas Jr. (b. August 1867), laster, Plymouth NM

Marcus M. Thompson, 7 Everett

Rayman Tibbetts, bds. 159 Center

William W. Tinkham (b. September 1859), dresser, bds. Benjamin F. Tinkham 75 Oak

Foster Wade (b. December 1871), sole layer, bds. E. H. Aldrich 14 Barrows

Mary E. Warren, bds. Francis Warren 107 Everett

Nelson C. White (b. March 1854), edge maker, 57 Everett

William H. Wilde (b. May 1863), 34 Pearl

Kenelm Winslow (b. September 1856), laster, 14 Pearl

Winfield H. Wood (b. February 1882), “tacker on”, bds E. D. Wood 36 North

Thursday, December 16, 2010

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington Robbery

The Middleborough branch factory of Hathaway, Soule & Harrington achieved an unexpected local notoriety when during the early morning of October 25, 1895, its safe was robbed. Fortunately, a clipping from the Middleboro Gazette recounting the incident survives to recount the tale nearly in full.

For the first time for many years safe robbers visited our town, Thursday afternoon and night. Shortly after 1 o'clock, as watchman Charles Crandall of Hathaway, Soule & Harrington's shoe factory on Cambridge street was descending to the main entry of the factory in making his usual round, he was seized by four men, who immediately blindfolded him and proceeded to blow open and rob the safe.

The burglars evidently watched Mr. Crandall as he went to various points about the building, and when he was on the upper floor forced open the front door. Seating themselves where they were not seen by the night watchman until he stepped off the last stair they had him completely by surprise and at their mercy in an instant.

Mr. Crandall at first thought it a joke of some of the shop hands. He carries a cane to assist him in going up and down stairs, and when they first seized him with the remark, "We've got you," he lifted this stick above his head, saying, "You have, have you." Mr. Crandall still thought it a joke, and had no idea of striking with his stick, but one of the fellows said afterward that he was about to deal him a stunning blow, when thoughts of his own father caused him to change his mind, and Mr. Crandall escaped personal injury.

"You are a cranky little fellow, but it is of no use. We won't hurt you if you keep quiet." Realizing that one against four was an unequal contest, he submitted to being blindfolded. The robbers sat him upon the stairs, and one on either side stood by him while the other two proceeded to the office, where they blew open the safe, as the watchman thinks, by the use of powder, judging from the smell.

Judging from the cool manner in which they proceed, Mr. Crandall thinks confederates were outside. He remarked to them that he at first thought that they were some of the employees, and that the thought of burglars had not entered his mind. "How do you know we are not employees of the factory," asked one of them. "There are only four of you," said Mr. Crandall. "You don't know but there are twenty of us, but you have the number inside right," was the reply.

Mr. Crandall asked them if they had not been at work near by on another break a short time before, but they said "no," and he thinks that a slight noise he heard a little while before was caused by forcing the door.

The safe was blown open probably at 2.25 a. m., as the clock over the safe stopped at that time. Two of the fellows were masked and above average height. The other two Mr. Crandall cannot describe, as he did not see them. The report made by the explosion was quite loud, and was heard by several residents in the neighborhood, but nothing was thought about it as the trains make so much noise all night. The door was blown completely off and several chairs demolished and a window broken.

The robbers were sadly disappointed when they rifled the safe. They secured only a very small sum.

That a former employee was a leader in the break seems to be indicated by several things said. When they found so little money this man remarked, "When I used to work here the pay roll was kept in the safe." They seemed very much chagrined when they realized how little they secured.

The watchman asked if they found much, and one of them answered, "Not enough to pay for our trouble." Mr. Crandall told them that the firm's methods had changed of late relative to money matters.

William H. Wilde, the book-keeper at the factory, is away on his wedding tour, so that the exact amount they secured could not be learned. The weekly pay roll frequently amounts to $2,000, and today is pay-day. It was this sum that the gang undoubtedly hoped to secure. Mr. Hathaway of the firm was in town, yesterday, but the money for today's pay-roll was not put into the safe.

Failing to secure any amount of cash they turned their attention to tools. They inquired where the machine room was, but Mr. Crandall told them he knew very little about the particular places where tools were kept, as he never visited the factory in the day time.

"How do you get down cellar," asked the apparent leader. "That's a pretty question for one to ask who has worked here as long as you have," retorted one of his mates.

The gang appeared in no hurry to leave. They treated Mr. Crandall with the utmost consideration. Before they left they carried him to the workroom and tied him into a chair, so that he could no get away.

When engineer W. H. F. Pettee arrived, early in the morning, he was greatly surprised to find the door open, but he was speechless when he beheld the watchman bound and blindfolded. He quickly released him and learned the night's events.

It is stated tat one of the men dropped a 'kerchief and came near leaving it. When he discovered it, he exclaimed, "I musn't leave that; Emma always puts my name on them."

Their whole conduct seems to indicate that they were not experts at the business.

The same gang probably visited Mount Carmel railroad station, Thursday afternoon, during the absence of the station agent, and secured about $10 from the money drawer. It was a poor job all round.

The shoe factory break was the most sensational since the memorable "town safe" robbery, nearly 25 years ago, when the robbers secured a large amount in valuable bonds and cash.

Mr. Crandall is none worse for the night's excitement, except that it was quite a shock to his nerves; but he showed no white feather. He is glad however, that the company are not heavy losers by the robbery.

The greatest loss to the corporation will probably be the damage to the safe. So far as can be learned, no tools of value were taken.

Little else has been left on record of the crime, although it remained in the memory of the Alden family which managed he factory at the time, and was later passed down through the Barden family. In 1989, George M. Barden, Jr., recalled the incident in the pages of the Middleborough Antiquarian and told a slightly different version in which Crandall, while not implicated in the robbery itself, was culpable for permitting unfettered access to the factory by the perpetrators.

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington employed a Civil War veteran to serve as night watchman at the factory. He would come to work in the evening and spend the night all alone in the five-storied building, making the rounds periodically to make sure everything was secure. When two congenial young strangers made his acquaintance and offered to keep him company through his lonely hours he was only too glad to accept. For a week or more they spent almost every night with him at the factory, whiling away the time at checkers and listening to his tales of Civil War adventures. They also took note of his inspection routine. Finally, one fateful night, after the three had finished the midnight lunch, one of the strangers said:

"Old man, we are going to tie you in your chair to keep you out of trouble and then you will hear an explosion louder than anything you ever heard in the Civil War!"

Within minuted the watchman was securely tied to his chair and the promised explosion, when the strangers blew the door off the safe in the office, was indeed impressive. Their carefully planned getaway involved the use of a railroad handcar, the old-fashioned kind that was powered by hand pumping, previously placed by the yeggs on the tracks that ran just behind the factory. Taking their bag of loot, they raced to the handcar and began pumping feverishly to put Middleboro behind them as fast as possible - a scene right out of the Keystone Cops. Family tradition has told this writer that they made it to Bridgewater before they were apprehended and the loot recovered.

Despite the impression left by Barden's account, the perpetrators appear to have gone undiscovered for at least a short period of time as indicated by the Middleboro Gazette which reported that "the recent Hathaway, Soule & Harrington burglary case is in the hands of two of the most skillful detectives in this section." While there was much initial uncertainty regarding the amount of money taken from the safe, the newspaper report confirmed that "the amount taken by he cracksmen is now definitely determined to have been less than $50." Though the burglars had hoped to discover the firm's large payroll in the safe, a number of developments had conspired against them including a recent state law which required employees of corporations to be paid weekly and with which the firm had been in compliance with since the summer. Most crucially and for reasons now unknown, the payroll was not placed in the factory safe on Thursday, October 24.

Barden, George M., Jr. Middleborough Antiquarian, "A Shoe Business, A Robbery and a Fire", 27: 3, December, 1989, 5+.

Middleboro Gazette, "Bold Burglars", October 25, 1895:4; "Middleboro", November 1, 1895:4; "Twenty-Five Years Ago", August 6, 1920:2.

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington Images

The following is a series of images of the interior of the Hathaway, Soule & Harrington factory on Cambridge Street which I acquired a number of years ago. They had once belonged to George M. Barden, Jr., great-grandson of Andrew Alden who had served as superintendent of the

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington office, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

Pictured is the management and office staff of the Hathaway, Soule & Harrington plant at Middleborough in the late 1890s. From left to right are clerk William H. Wilde, superintendent Andrew Alden, assistant superintendent Arthur H. Alden, bookkeeper Sadie Ryder, and Alice Roberts. The office embodies a no-nonsense business approach with the bare minimum requirements. Wilde in his role as clerk is neatly-dressed, though both Aldens wear protective overgarments in order to keep their clothes clean while on the factory floor. A large freight map on the wall indicates the extent of the Middleborough plant's business. Andrew Alden had initially learned the shoe trade at North Middleborough where he made shoes by hand on Plymouth Street. In 1881, he was instrumental in the formation of Alden, Leonard & Hammond which relocated to Cambridge Street in Middleborough in 1886. Following the acquisition of Alden, Leonard & Hammond's interests in 1887 by Hathaway, Soule & Harrington, Alden remained with the latter firm as superintendent. He retired in 1900 when Hathaway, Soule & Harrington closed the Middleborough branch. Alden's son, Arthur Harris Alden, had entered the shoe trade following his graduation from the Pratt Free School, and he joined his father at Hathaway, Soule & Harrington where he acted as foreman and later assistant superintendent. In 1900, he became the senior partner in Alden, Walker & Wilde which was established that year. William H. Wilde served as clerk of the Hathaway, Soule & Harrington Middleborough operation before joining Alden and George W. Walker in the formation of Alden, Walker & Wilde.

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington cutting room, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

One of the first steps in manufacturing shoes was the cutting of the leather. Leather was procured by experienced buyers in Boston which, thanks to the numerous shoe manufactories operating throughout New England, was the world's largest leather market at the time. Cutters required both great strength and dexterity and were skilled at maximizing the number of uppers which could be cut from each piece of leather. By this time, cutters specialized in the cutting of uppers and the cutting of soles. The worker marked with an "x" in the photograph is August P. Johnson. The son of Swedish immigrant parents, Johnson worked as a cutter in the local shoe industry for a number of years. Born in December, 1872, Johnson was about 25 when the photograph was taken. In 1898, he married Mary F. Shuman.

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington stitching room, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

This view likely depicts the stitching room. Once the uppers were cut, they were lined and stitched together. Much of this work was performed by women. The gentleman standing to the right and marked by an "x" is James Gardner Alden, the eldest son of Andrew Alden. Although records fail to indicate his position in the firm, it is likely that he was employed as a department foreman.

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington stitching room, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

Possibly another view of the stitching room. Carrie Shuman who is seated at the far end of the room is marked by an "x". She was one of several operatives who went to work at Alden, Walker & Wilde when Hathaway, Soule & Harrington closed its Middleborough plant. Sanborn fire insurance maps of the era indicate that part of the plant's fire protection included "pails throughout" and a number of these galvanized buckets may be seen hanging near the ceiling. Although the visible clutter in the room raises doubts about the plant's concern for fire safety, the building was in fact equipped with fire escapes on either end of the structure, one of the earliest Middleborough manufactories with this provision.

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington stitching room, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

Yet another view of the stitching room. Unstitched uppers appear in the lower left corner of the photograph. The fabric pieces are apparently linings which would have been attached to the uppers during this stage of the work. Note that the women not only wear aprons to protect their clothing, but protective oversleeves as well.

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington lasting or McKay room, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

This view is possibly of the lasting room. Once the uppers were stitched, wooden lasts were inserted to facilitate the process of bottoming, that is the addition of the soles. Machines produced by the McKay Company helped revolutionize the process of stitching uppers to soles.

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

Like his brother Arthur, Frederic Lawton Alden joined the family in manufacturing shoes shortly after his graduation from school. The younger Alden appears towards the center of the photograph marked by an "x".

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington, Cambridge Street, Middleborough, MA, photograph, late 1890s

The mechanized nature of the shoe manufacturing process is indicated in this photograph by the belts and shafting over the heads of the workers. While new machines greatly facilitated the production of shoes, they could prove hazardous to workers. In July, 1888, "a man named Farrington, of Middleboro, employed at Hathaway, Soule & Harrington's shoe factory, cut off a thumb a few days ago in some of the machinery. Lysander Richmond also cut his hand severely on the same day in the same shop." [Old Colony Memorial, "County and Elsewhere", July 19, 1888, p. 4].

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington History

The posts for today and the next few days are for Carole Tracey who has generously shared her own history in the past regarding Hathaway, Soule & Harrington, the firm established by her great-grandfather. Although principally a New Bedford company with offices later in Boston and New York, Hathaway, Soule & Harrington operated a branch factory at Middleborough between 1887 and 1900. What follows is a history of that branch.

|

"Hathaway, Soule & Harrington", from Illustrated Boston: The Metropolis of New England (New York, NY: American Publishing & Engraving Co., 1889), p. 131. |

In late 1887, Hathaway, Soule & Harrington purchased the interest of Alden, Leonard & Hammond of Middleborough which was occupying a manufactory which had been constructed the previous year on Cambridge Street by George L. Soule. A civic booster, Soule had employed salvaged lumber from the disassembled Nemasket Skating Rink to construct the 30x100 foot three-story factory in mid-1886 in hopes of luring industry to Middleborough. Upon completion of the building, Alden, Leonard & Hammond relocated from North Middleborough and occupied the manufactory only briefly before selling their interests to the New Bedford firm.

As had their predecessors, Hathaway, Soule & Harrington leased the Cambridge Street plant from Soule, commencing operations there in late December, 1887. Apparently pleased with the plant, the firm was rumored to be contemplating consolidation of its Middleborough and Campello branch factories in the former location, a step "which will about double the business,” according to one local newspaper.

While the rumored consolidation never took place, Hathaway, Soule & Harrington did enlarge the Middleborough facility, prompting the Middleboro News to urge residents to be “up and doing and secure the benefits likely to result from a factory employing 100 to 150 hands.” To facilitate its expansion, in December, 1889, the company purchased the manufactory building from Soule and acquired two adjoining lots in order to construct an addition which was likely raised at that time.

|

Hathaway, Soule & Harrington, advertisement, 1894 |

The firm marketed its product aggressively, and shoes were sold as far away as Australia, an accomplishment which led the Middleboro Gazette to remark, “the people at the antipodes take kindly to the Middleboro shoe.”

Production was increasingly mechanized during this period, and in January, 1895, the firm was testing lasting machines at Middleborough. The test must have proved successful, for in 1897, at least one lasting machine was installed in the factory and by 1898 there were six of them operating in the plant. The use of mechanical lasters, however, created problems when unionized lasters at Brockton struck against the lasting machine companies. Lasters at both Hathaway, Soule & Harrington as well as Leonard, Shaw & Dean at Middleborough were ordered out by the union, though the action had little impact as lasting was resumed by hand.

By 1895, the firm’s three plants were producing some 500,000 shoes annually for $1.5 million in sales. Of the 650 hands employed, about 200 were located at the Middleborough plant. The firm was noted for the high caliber workmen which it employed, “and many men have gone out of their factories to accept responsible positions elsewhere.” Hathaway, Soule & Harrington salesmen and managers also achieved important positions in other firms, as well. Henry Dean who had been employed 12 years by Hathaway, Soule & Harrington in 1897 became a partner in the Middleborough shoe firm of Leonard & Shaw which subsequently became Leonard, Shaw & Dean. Overseeing management of Hathaway, Soule & Harrington's Middleborough manufactory was superintendent Andrew Alden. The Alden family was deeply connected with the business, and Alden's three sons - James Gardner Alden, Arthur Harris Alden and Frederic Lawton Alden - each held positions in the Middleborough operation. Arthur and fellow Hathaway, Soule & Harrington associates George W. Walker and William H. Wilde would later co-found Alden, Walker & Wilde in Middleborough in 1900.

Production throughout the late 1890s remained high at Middleborough, and the plant appears to have operated at full capacity with 40 cases of shoes being produced daily. In fact, additional workers were hired in September, 1895, due to the pressures of “brisk” business.

The success of the Middleborough branch notwith-standing, as early as 1897, Hathaway, Soule & Harrington contemplated abandoning Middleborough. In response to an understanding that the firm would remain in town should a 40x100 foot addition costing $5,200 be constructed for them, a citizen’s meeting in Middleborough Town Hall raised $2,000 towards the cost, while company employees pledged another $1,000, as an inducement for the company to stay. By September, 1897, nearly all the money necessary to raise an addition had been subscribed, but "contrary to general expectations”, Hathaway, Soule & Harrington in mid-September, decided to close the Middleborough plant and consolidate operations at New Bedford.

Despite this decision which was reported in the local newspapers of the time, no immediate steps were taken to close the Middleborough plant which remained open for another two and a half years during which time business was steady, even overwhelming. Aggressive salesmen flooded the firm with orders in 1899, and demand was so high for the company’s product that the Middleborough plant was compelled to operate at night beginning in February of that year. New markets in Cuba and the Philippines which were opened as a consequence of the Spanish-American War, also fueled demand and the Middleborough plant became engaged in manufacturing “a large number of shoes” destined for Havana and Manila. The volume of work naturally necessitated the employment of additional operatives and not surprisingly the December, 1899, weekly payroll was remarked upon as the largest ever at the Middleborough branch when some $3,000 in weekly wages were distributed.

In March, 1900, definitive steps were taken to finally close the Middleborough branch and remove operations to New Bedford. The 200 Middleborough operatives were offered employment in the New Bedford plant and while some accepted, others remained at Middleborough, possibly enticed by the announcement in early April that Leonard & Barrows, Middleborough’s largest shoe manufacturer at the time, planned on adding an additional 300 jobs. Additionally, some remained to enter the employ of Alden, Walker & Wilde which opened a plant on Clifford Street at the time of the Middleborough branch's closure. That spring, in its final week, four railroad carloads of shoes and two of leather shoe findings were shipped from Hathaway, Soule & Harrington's Middleborough plant.

Sources:

Illustrated Boston: The Metropolis of New England. New York, NY: American Publishing and Engraving Company, 1889.

Middleboro Gazette, “Twenty-Five Years Ago”, January 23, 1920:2; ibid., June 4, 1920:5; ibid., August 6, 1920:2; ibid., August 13, 1920:6; ibid., September 10, 1920:7; ibid., October 1, 1920:5; ibid., October 29, 1920:3; ibid., November 11, 1920:3; ibid., January 21, 1921:3; ibid., March 25, 1921:4; ibid., June 3, 1921:7; ibid., February 3, 1922:6; ibid., June 16, 1922:6; ibid., September 1, 1922:8; ibid., September 22, 1922:7; ibid., December 8, 1922:5; ibid., September 28, 1923:10; ibid., November 23, 1923:6; ibid., February 8, 1924:9; ibid., March 7, 1924:6; ibid., December 5, 1924:5; ibid., December 12, 1924:7; ibid., January 16, 1925:6; ibid., April 3, 1925:8; “Middleboro”, December 29, 1905:4; ibid., January 5, 1906:4;

“Middleboro, Plymouth Co., Mass.” NY:Sanborn-Perris Map Co., Limited. May, 1891

“Middleboro, Plymouth Co., Mass.” NY: Sanborn-Perris Map Co., Limited. June, 1896“Middleboro, Plymouth County, Mass.” NY: Sanborn-Perris Map Co., Limited. April, 1901.

Old Colony Memorial, August 5, 1886:1; “County and Elsewhere”, August 26, 1886:4; ibid., September 2, 1886:4; ibid., June 9, 1887:5; ibid., December 29, 1887:1; ibid., March 22, 1888:4; ibid., July 19, 1888:4; ibid., November 9, 1889: 5; ibid., December 14, 1889:4; March 31, 1900:3

Saturday, October 16, 2010

The Burning of Alden, Walker & Wilde, 1904

On October 4, 1904, what was described as the worst fire in Middleborough in over 20 years virtually destroyed the shoe manufactory of Alden, Walker & Wilde on Clifford Street and compelled the firm to remove from town. Built in 1875, the manufactory building ruined in the blaze had initially been occupied by the Domestic Needle Works and its successors, and later by the W. H. Schlueter & Company, before being acquired by Alden, Walker & Wilde.

Organized in 1900 by Arthur H. Alden, George W. Walker and William H. Wilde who had formerly been associated with Hathaway, Soule & Harrington, an earlier shoe manufacturing firm in Middleborough, Alden, Walker & Wilde rapidly became one of the principal shoe producers in town. At the time of the 1904 fire, the firm employed some 100 hands to manufacture high quality men’s dress shoes and was reportedly paying high wages.

During the early morning of the October 4th, Eldred R. Waters who resided around the corner on Wareham Street was the first to notice the fire which originated in the rear of the building. “He rushed to the road, crying ‘fire’ and soon residents of the dwellings surrounding responded and an alarm was pulled in.” Due to some unspecified malfunctioning of the alarm, however, there was a delay in the fire department’s response, a delay which would ultimately prove “costly.”

The fire spread through the wood frame building rapidly, fueled by the shoes, leather and paper packing boxes within. “Floors dropped under the weight of the shafting and heavy machinery, sections of the building and roof fell off, the firemen narrowly escaping injury."

Middleborough Fire Chief Charles W. Kingman described the difficulty of the task in the report which he wrote subsequent to the fire:

Thirteenth alarm, October 4th, at 5.30 a. m., from boxes 34 and 35, for a fire in the shoe factory of Alden, Walker & Wilde, Clifford street. This was the largest fire the town has had since the burning of the Leonard & Barrows factory, some twenty years ago. Responded to by the entire Department. The building must have been burning for some time before it was discovered, as the two upper stories and roof were well under way when the Department arrived. It was at once seen that we had a hard fight before us. The extension ladder was at once raised to the roof of the Jenks building and Hose Companies 1, 2 and 6 and Chemical Engine were at once put to work, and with the help of a powerful stream from the Jenks factory, which is excellently equipped for fire fighting, the fire was confined to this one building. The Jenks building caught once on the end of the jet and was somewhat scorched by the intense heat. Hose 3 and 4 were held in reserve. Both pumps were used at the Pumping station, something that has not happened since the LeBaron Foundry fire in 1895, and after they were put on the pressure was very good.

“When the roof went through a big cloud of cinders arose, and as they dropped they fell on the residences of J. H. Moody and James Curley, on the opposite side of Clifford st. Lines of hose were immediately sent up on these buildings, and firemen remained on top of them to watch for a blaze. The sparks were also carried on Wareham st. to the blacksmith shop of T. F. Ford, and but for the prompt action of the firemen there might have been another blaze there.” The Jenks Building on the corner of Wareham and Clifford Streets which stood beside the Alden plant also suffered. The intensity of the heat shattered glass window panes and for a time it was thought that the rear portion of the building would be consumed as well.

When it became evident that the Alden, Walker & Wilde plant could not be saved, efforts were directed at removing as much of the finished product as possible, “some of which were packed in cases, some on the racks to be packed, while others were almost ready for the packing stage.” Also saved from the flames were Alden, Walker & Wilde’s records and the shoe samples which had only recently been produced and which were invaluable in convincing prospective buyers to place orders with the shoe firm. The shoes were placed in the custody of the fire police and were later removed to the vacant factory of C. W. Maxim.

Kingman’s report continues:

Although it was not long before the fire was under control, it was nearly 11.30 before it was entirely out. Good work was done by the Fire Police and volunteers in removing property from the building, and we were fortunate in having no wind. The boiler and engine and the books and samples were saved, and perhaps $1000 worth of shoes in a damaged condition. The Department certainly did good work, and we were very fortunate in that no one was injured and that a serious conflagration was averted. Loss, perhaps $35,000. Cause of fire unknown.

The burning of the building and its contents produced an enormous plume of black smoke which covered the southern portion of town, attracting the attention of curiosity seekers who “flocked” into town to see the devastation. What they saw was only a semblance of the manufactory which had previously stood there. The two upper floors were nearly totally destroyed. And while the ground floor remained, it was heavily damaged by both smoke and water. (Relatively unscathed was the one-story brick engine house at the rear of the building which stood until at least 1906).

Alden estimated the loss to be from $30,000 to $40,000, including $10,000 worth of sole leather alone which had been inside the plant. Only a portion of the loss was covered by insurance, and insurance agents themselves considered the building a total loss. Yet despite this discouraging assessment, immediately following the fire, the firm vowed to remain in Middleborough and rebuild.

The cause of the fire appears unknown to posterity, though the rapidity with which the blaze spread through the building was attributable in part to the lack of any fire apparatus or a watchman at the Alden, Walker & Wilde plant. Kingman's praise of the preparedness of the neighboring Jenks Building, in contrast to that of the Alden plant, may have in fact been intended as a subtle criticism of the latter firm.

The remains of the building stood for a number of weeks during which time workers were engaged in clearing the debris. The remaining sole and upper leather was purchased by speculators, and damaged shoes were sold as “bargain lots”. The machinery was crated up and removed by the United Shoe Machinery Company which shipped it to Winchester. In the meantime, the company had relocated to North Weymouth where it purchased the firm of Torrey, Curtis & Tirrell and to where the undamaged portion of the Middleborough plant was transferred.

On October 21, a heavy rain and windstorm blew over one side of the remaining ruins and the danger of the remaining collapsing prompted Superintendent of Streets J. C. Chase to fence off the street around it. The following day, a force of men removed the remainder of the upper portion of the factory, leaving the hollow shell of the ground floor. In December, this too was finally leveled. What lumber could be salvaged was acquired by Charles B. Cobb for the construction of a storehouse.

Despite the fact that Alden, Walker & Wilde had relocated to Weymouth, rumors continued to circulate about Middleborough that the firm proposed returning to town and that local contractor B. F. Phinney had been engaged to construct a new manufactory for the firm. In early December Phinney denied any knowledge of such a plan. The company never returned to Middleborough.

Sources:

“Annual Report of the Board of Engineers of the Fire Department” in Annual Reports of the Officers of the Middleboro Fire District, and the Nineteenth Annual Report of the Water Commissioners for the Year 1904. Middleboro: Middleboro Fire District, 1905.

Old Colony Memorial, “News Notes”, October 29, 1904, page 3.

Unidentified newspaper clippings, James H. Creedon collection, Middleborough Public Library,”Middleboro Has Bad Fire”, October 4, 1904; “Shoe Factory Burned”, October 4, 1904; October 17, 1904; “Middleboro”, October 22, 1904; “Middleboro”, October 23, 1904; “Middleboro”, December 3, 1904.

Friday, May 21, 2010

Cotton Manufacturing at the Lower Factory Established, 1811

.JPG) The honor of first establishing textile manufacturing in Middleborough must rightly lie with a family that receives very little mention in either of the two published town histories: the Shephard family of Wrentham, Massachusetts, who in 1811 established a cotton manufactory on the Nemasket River at the Lower Factory, later the site of the Star Mill.

The honor of first establishing textile manufacturing in Middleborough must rightly lie with a family that receives very little mention in either of the two published town histories: the Shephard family of Wrentham, Massachusetts, who in 1811 established a cotton manufactory on the Nemasket River at the Lower Factory, later the site of the Star Mill.Prior to the arrival of the Shepards, the Lower Factory was a relatively bustling industrial area. A dam just upstream from East Main Street had long harnessed the natural drop in the river and powered a grist mill, a carding mill and a fulling mill (which processed woollen cloth). On December 14, 1810, the owner of the grist mill, Jacob Bennett of Middleborough, sold to Captain Benjamin Shephard, Junior; Benjamin Shephard III; and Oliver Shephard, all of Wrentham, the land and water rights at Bennett's Mills "for the purpose of working a Cotton Mill or any other Factory or works." Excepted from the conveyance, however, were the right of the carding mill owners, the "Cloathing Mill" or fulling mill, and Bennett's own grist mill. At the time, the Shephards also purchased other nearby lands.

The Shephards who would prove the driving force behind the early textile-related industrialization of Middleborough, had been instrumental in the development of the textile industry in Southeastern Massachusetts. About 1793, Benjamin Shephard had built a cotton manufactory in an area of South Wrentham (now Plainville) later known as Shephardville. This factory, partially financed through a $300 loan from the Massachusetts General Court which sought to promote the cloth manufacturing industry, was "probably the third [cotton manufactory] to be operated by water power in this country," the historic Slater Mill in Pawtucket having been built only earlier that same year.

A series of embragoes beginning in 1807 and maintained throughout the War of 1812 provided protection from British competition for the nascent American textile industry, and prompted the establishment of cotton mills throughout Rhode Island and Southern Massachusetts during this period.

While it is not readily clear what attracted the Shephards to Middleborough, there was a local connection in that Captain Shephard's daughter, Susanna, was married to Dr. Thomas Nelson of Middleborough, and the couple resided in that section of Middleborough that is now Lakeville until 1801. The Shephards may, therefore, have become acquainted with the industrial potential of the Nemasket River at that time.

Contrary to Weston's History of the Town of Middleboro, the Shepard's cotton manufactory at the Lower Factory was constructed in 1811 prior to the company's 1815 incorporation, built on the site of the old fulling mill, as indicated by deeds from that period. It therefore probably predates Washburn and Peirce's New Market cotton manufactory which was erected on the river at the Upper Factory at what is now Wareham Street sometime about 1812 or 1813.

Though there are no existing views of the Shephard's 1811 mill, the mill building would have been a two to three-story wood-frame building with large windows to illuminate the interior of the carding and spinning rooms and a waterwheel to power the machinery - a typical design for New England cotton mills during that era.

The Shephard family moved to formally establish the Middleboro Manufacturing Company on January 1, 1812, as a firm to manufacture cotton yarn and cloth, with Benjamin Shephard, Jr., Horatio G. Wood; Amos Cobb; and Alanson Witherell, all of Middleborough; Oliver Shephard of Wrentham; Thomas Nelson of Bristol, Rhode Island; and George Bicknell of Philadelphia. The Company assumed the liabilities incurred previously by the Shepards "in Erecting, and establishing a Cotton Maunfactory & other buildings," and took possession of these and the "Machinery, land, water privileges, ways and easements, and also the present manufactured & unmanufactured stock on hand," The Company was divided into thirty-six shares of $500 each, distributed to Benjamin Shephard (ten shares), Oliver Shephard (ten shares), Thomas Nelson (six shares), George Bicknell (six shares), Horatio G. Wood (two shares), Amos Cobb (one share) and Alanson Witherell (one share).

The Middleboro Manufacturing Company continued to purchase nearby land and houses for its needs, some of the land being used as a bleaching green or "whitening yard." The Company was eventually incorporated in 1815 by Benjamin Shephard, Jr.; Thomas Weston; Horatio G. Wood; Nancy Nelson; Sarah W. Shephard; and Alanson Witherall.

The Company's mill was run in accordance with the so-called Rhode Island system of operation whereby local families would be employed as mill operatives, as opposed to unmarried young women. Cotton yarn would be produced at the mill and the weaving, most likely, would have initially be done on hand looms in the workers own homes, and returned to the factory.

Sadly, little is yet known of the history of the Middleboro Manufacturing Company. It seems to have operated for a period before the Shephards eventually relinquished control of the mill to the business partnership of Peter H. Peirce and Horatio G. Wood, which added the manufacture of shovels to the business before yielding, in turn, to the larger Star Mill. The Shephards continued to operate their South Wrentham mill "until the business reverses of 1837, when they were forced into bankruptcy," a sad fate for such an enterprising family.

Illustration:

Replica of a Crompton Spinning Mule (detail), Slater Mill, Pawtucket Rhode Island, photograph by Mike Maddigan, July 24, 2005

Crompton's spinning mule revolutionized textile production and helped lay the foundation of the industrial revolution by permitting the large-scale production of high-quality yarn. Although centered in the Blackstone Valley of Rhode Island and south central Massachusetts and developed following 1793, America's early textile industry soon spread to nearby areas, including Middleborough which had two cotton manufactories in operation by 1813.

Saturday, May 15, 2010

Industrious Middleborough, 1860

In the summer of 1860, the Hyannis Messenger visited Middleborough and remarked upon the industriousness of its residents:

In the summer of 1860, the Hyannis Messenger visited Middleborough and remarked upon the industriousness of its residents:The signs of industry were everywhere visible. Even the [Peirce] academy students ... were employed during their leisure hours in making shoes. We entered a great many private dwellings and found women and children busy - boys as well as girls - either binding shoes, or braiding straw for bonnets, or occupied in some other equally useful way.

Both shoe-making and straw braiding for the local straw hat industry were cottage industries pursued by Middleborough residents through the mid-19th century. Many farmers traditionally had been accustomed to producing shoes during the relatively slack winter months, and as the modern shoe industry developed in the mid-1800s, their skills were utilized to help produce rudimentary shoes and boots which were completed in local manufactories. Meanwhile, straw hat manufacturers established a similar system of rural outwork for local residents, primarily women, whereby straw would be provided for them to braid in their homes. The so-called "braid cart" would collect the completed plaits which were used to produce hats and bonnets in the local manufactory. Shortly after the Messenger's comment, the local production of both shoes and straw hats was centralized in large manufactories including Leonard & Barrows and the Bay State Straw Works.

Illustration:

Plaited Straw Bonnet, photograph by Michael Maddigan, April 30, 2007

Bonnets manufactured of braided straw such as this were typical of those produced in Middleborough in the early and mid-19th century. Rural outworkers produced straw plaits in their homes which were later used by manufacturers to produce such intricate head wear and which promoted Middleborough's reputation for industriousness.

Source:

Middleborough Gazette and Old Colony Advertiser, August 4, 1860.

Friday, May 7, 2010

Clifford Street Needle Works

The manufacture of sewing machine needles in Middleborough in the decade following 1875 has largely been forgotten. And though the industry was short-lived, it was significant in that it reflected in part Middleborough’s initiative in establishing a diverse industrial base, a development which would help the community weather economic fluctuations better then other communities dominated by a single industry.

The manufacture of sewing machine needles in Middleborough in the decade following 1875 has largely been forgotten. And though the industry was short-lived, it was significant in that it reflected in part Middleborough’s initiative in establishing a diverse industrial base, a development which would help the community weather economic fluctuations better then other communities dominated by a single industry.The Domestic Needle Works

Middleborough's needle-making industry was established in the form of the Domestic Needle Works on Clifford Street. Established in 1875, the firm marked the successful culmination of an attempt by concerned citizens of the community to lure new business to town, business which was desperately desired given the economic depression at the time.

As early as July, 1875, it had been reported that Middleborough was attempting to establish a sewing machine needle manufactory. "The people of Middleboro are interesting themselves in a proposition to induce parties to start a needle factory in that town, hoping thereby to furnish employment to a hundred or more persons. The proprietors offer to relinquish the whole control of the business to stockholders, and guarantee a profit of fifteen percent."

Though efforts to locate a needle works in town encountered a number of difficulties along the way, following a series of community-wide meetings in the early fall of 1875, the final obstacles were cleared and by November the $40,000 required for the venture had been fully subscribed. A board of directors composed of J. Wallace Packard, John B. LeBaron, Dr. Ebenezer W. Drake, Albert Alden, and George L. Soule was named.

Packard was the sole non-Middleborough resident among the group, though he was also the only individual among them acquainted with needle-manufacturing. In March, 1858, Packard had begun the manufacture of stitching and sewing machine needles at North Bridgewater (now Brockton), Massachusetts, where the dominance of the shoe industry promoted ancillary industries such as awl and needle-making. Packard probably learned the trade from Charles Howard who had established a needle-making firm at North Bridgewater in 1857, and it was likely Packard who convinced the Middleborough group to establish a needle works.

The organization at this time of a number of sewing machine needle companies – including the Domestic Needle Works of Middleborough – marked an attempt by American manufacturers to break the stranglehold of British firms which then monopolized the world market for machine needles, including two-thirds of the American market. Entrepreneurs like Packard and investors like LeBaron, Drake, Alden and Soule no doubt saw financial reward in the opportunity of breaking the British monopoly.

Upon its formation, the Domestic Needle Works Company purchased from Philander Washburn an empty lot on the west side of Clifford Street for $800 whereupon a woodframe factory was erected. (The drive-up for the Mayflower Cooperative Bank now occupies the site).

The contract for constructing the three-story factory building was given to Joshua Sherman and Jairus H. Shaw of Middleborough, "at a price generally understood as somewhere about $3,000," and the Plymouth Old Colony Memorial marvelled at the fact that the building was to contain over one hundred windows. The needle-making machines were to be driven by steam power produced by a 20 horse-power “New York Safety” engine which was to be housed in a fire-proof engine and boiler room. Steam was carried throughout the building by means of a network of pipes which was installed by Cutts and Jordan, machinists from Taunton.

To provide the necessary water for the boiler, a deep well was driven on the property as Middleborough at that time was still without municipally-supplied water. Although the well began to fail in 1883, in December of that year “its failing supply of water [was] renewed through the agency of a charge of atlas powder exploded in the rock at the bottom. Water from a lower strata came up through the fissures created, giving an ample supply.”

The needle manufactory was reported as nearing completion in late December, 1875, not surprising since the contractors were given a 30-day window in which to complete construction. At this same time, or shortly thereafter, a small “oil house” was constructed at the southwest corner of the property. It was built as a separate facility in order to provide remove the flammable material used in the production of the needles away from the main plant.

The Needle-Making Process

At the time that the Domestic Needle Works was founded, mechanical production of sewing machine needles was a growing industry. In 1864, Orrin L. Hopson and Herman P. Brooks of Connecticut had developed a machine for compressing steel wire and patented it as “An Improvement in Pointing Wire for Pins”. The machine was promoted as a device which could produce sewing machine needle blanks of superior quality, and it became the foundation of the modern sewing machine needle industry.

Needles at the Domestic Needle Works were produced by the cold swaging or cold forging method wherein room temperature steel wire was compressed between a series of metal dies. The process of needle manufacturing at the time was described in 1886 by George Bleloch who left a carefully documented record of the process as conducted by the National Needle Company of Springfield, Massachusetts. It is likely that a very similar process, though on a smaller scale, was followed on Clifford Street.

The wire is drawn of suitable size for the shanks or but end of machine needles, and is received at the needle factory in coils weighing about 50 pounds each. The coil is placed on a reel, and fed through one of the straightening and cutting machines, four of which are in constant use. These machines are automatic, and deliver the wire, cut into uniform lengths, each piece containing sufficient stock for the needle which is to be made from it. The ends of the small pieces of wire being rough, they are next placed in the hopper of the butting machine, and are carried between two highly-speeded emery wheels, and come through with the ends ground to a conical shape, thus finishing one end, which is to be the shank, the part of the n that is held in the needle-bar of the sewing-machine, and preparing the other end to enter the dies of the compressing or swaging machines which perform the next important operation.

The wire is drawn of suitable size for the shanks or but end of machine needles, and is received at the needle factory in coils weighing about 50 pounds each. The coil is placed on a reel, and fed through one of the straightening and cutting machines, four of which are in constant use. These machines are automatic, and deliver the wire, cut into uniform lengths, each piece containing sufficient stock for the needle which is to be made from it. The ends of the small pieces of wire being rough, they are next placed in the hopper of the butting machine, and are carried between two highly-speeded emery wheels, and come through with the ends ground to a conical shape, thus finishing one end, which is to be the shank, the part of the n that is held in the needle-bar of the sewing-machine, and preparing the other end to enter the dies of the compressing or swaging machines which perform the next important operation.The compressing machine is a triumph of inventive genius and mechanical skill, and is purely automatic. It reduces the wire, by means of rapidly vibrating dies, to the size for the blade of the needle; the same operation elongating it to the length required for a needle-blank. Twenty-five of these compressing-machines are in use, each one having a capacity for swaging 3,000 [needle]-blanks a day.

Twenty-five pairs of dies, each pair coming in contact 4,000 times a minute, create a din that reconciles one to investigate in less-noisy quarters. We will, therefore, follow the blanks from the compressing-room to the pointing department, for soft-pointing, so-called to distinguish it from the finish-pointing that is done after the needles are tempered.

The self-pointing is performed automatically by means of an ingenious machine that takes the blanks from a magazine, clips them to a uniform length, and carries them across the face of an emery wheel, shaping the points, but not making them sharp, as sharp points would be injured in passing through succeeding operations. Grooving follows soft-pointing, and is an operation requiring precise yet strong machinery, susceptible of the finest adjustment. The n when grooved is held in a clamp between two parallel spindles, on the end of which are fine steel saws or cutters. The clamp is fastened to a sliding bed, and grips the n as it carries it between and in contact with the cutters. One groove is short; the opposite one is cut the full length of the n-blade, and is intended to hold and protect the thread while the n passes through the fabric in sewing. The grooving-machines are partly automatic, one person being able to attend three machines.

The eye-punching is next in order -- a delicate operation, bringing into play mechanical skill, and requiring nimble fingers. It is performed by young men of from 16 to 24 years of age, the most expert being able to punch 16,000 eyes a day. The needles are now ready to be stamped, which is done by an automatic machine which rolls the n over the face of steel type with sufficient pressure to impress the name and size on the shank.

Most modern sewing-machines use self-setting needles, and this feature is secured in different ways; some needles are notched at the end of the shank, others have the shanks slabbed or ground off on one side, while some have a groove cut through the shanks.

These devices prevent the needle entering the needle-bar of the sewing-machine in any but the correct position. Ingenious machines are used in each of these operations. Notching and grooving the shank precede tempering; slabbing is subsequently done with emery wheels. Sixty per cent of the total cost of making a needle is expended in material and labor before it is ready for hardening and tempering; and a mistake in either of these operations is not only vexations, but expensive.

The finest grade of steel is a sensitive and capricious metal, and requires the most delicate and patient treatment in bringing it to a tough and elastic temper. In the process of hardening, the needles are submitted to the blaze of a charcoal fire until they are heated to a cherry-red color, and they are then chilled in an oil bath. When taken from the oil, they are washed in hot water charged with sal-soda, to remove the oil, and are then ready for tempering, which is done by again heating, this time in an oven heated to about 500 degrees, where the needles do not come into direct contact with the fire. If all these operations have been successful, the needles are now as though and elastic as a Damascus blade; and the series of polishing operations which follow are intended to bring them to a high finish, especially the eyes and points.

The first of the polishing operations is called brass-brushing, and the needles are prepared for it by being fastened in clamps; the blades and grooves are exposed to the action of a brush made of fine brass wire, and revolving 6,000 times per minute. A paste of fine emery and oil is used with the brush, and a high polish and smooth surface is the result.

Without being released from the clamps the needles are taken to the threading-room, where girls 15 to 18 years of age thread each needle with half a yard of best Sea Island cotton, the size of the thread corresponding to the size of the needle.

They are now ready for the eye polishers, who stretch the threads on a frame, and draw them as tightly as the strings of a harp.

Oil and fine emery are freely applied; and the clamp, full of needles, is drawn rapidly back and forth on the threads, until by a keen sense of feeling the operator knows the eyes to be smoothly polished.

The needles are again polished, but this time on a brush made of horse-hair, after which they are sent to the inspecting-room, where every needle is closely examined, and all imperfect ones condemned and destroyed. This close special inspection is maintained to correct any oversight on the part of the inspectors stationed in each department of the factory to scrutinize the needles as they pass through the various operations.