The following item is posted in response to a query I had regarding President William Howard Taft's 1912 visit to Middleborough. The article was originally published in the Middleboro Gazette and republished in the Middleborough Antiquarian in May, 1989.

Though progressive Republicanism was never as influential along the East Coast as it was in the West and Midwest, it did create an enormous pull on sympathies of Middleborough voters. At the start of this century, as many of the state's urban voters began taking to the Democratic Party, many rural communities in southeastern Massachusetts, including Middleborough, began developing a progressive Republican bent. The high water mark of progressive Republicanism in Middleborough was the brief period of 1912-13. During that time, the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party, under the aegis of Theodore Roosevelt, exerted a tremendous impact upon the political life of both the town and the nation. The 1912 presidential campaign brought both Roosevelt and President William Howard Taft to Middleborough in a clash of progressive and conservative Republicanism. The 1914 elections, however, sounded the death knell for Bull Moose Progressivism in Middleborough as previously disaffected progressive Republicans returned to the fold of a liberalizing Republican Party or joined the ranks of the burgeoning Democratic Party.

Bull Moose Progressivism, itself, was an indirect consequence of a political maneuver made by Roosevelt. Following election to the White House in his own right in November, 1904,the progressive Roosevelt renounced a third term for himself as president in the "bully pulpit," though this did not prevent him from personally hand-picking his successor - Secretary of War William Howard Taft. Despite a year-long African safari with his son Kermit followed by a triumphal European tour, Roosevelt could not arrest the presidential itch and by February, 1912, considering Taft disloyal to the cause of progressive Republicanism, Roosevelt declared, "My hat is in the ring" for a third presidential term.

Vying with Roosevelt for the Republican bid were progressive Wisconsin Senator Robert "Battle Bob" La Follette, who sought to deprive Roosevelt of the mantle of progressive Republicanism, and President Taft, candidate of the conservative or "stand pat" Republicans. La Follette virtually disqualified himself at the beginning of February with a rambling and incoherent speech, a consequence of overwork, while Taft had his own drawbacks. Taft's tendency to fall asleep in public (once, as a front row mourner, he drifted off at a funeral to the utter horror of his military aide, Archie Butt), his obvious corpulence, his heavy reliance upon arch-conservative Speaker of the House "Uncle Joe" Cannon of Massachusetts and his responsibility for the loss of the House Republican majority in the 1910 election were all detriments to the Taft campaign. Nor did it help that the president self-deprecatingly referred to himself as both a "cornered rat" and a "straw man" in the campaign.

In contrast, the dynamic T. R was enormously popular with the rank and file Republican voters and he hoped to win numerous delegates in the 13 presidential primaries, 1912 being the maiden year of the primary system. The Massachusetts primary was scheduled for Tuesday, April 30, and both Roosevelt and Taft spent much time in the commonwealth posturing for the event.

On Friday evening, April 26, President Taft gave a major address in Boston which left him physically and emotionally exhausted. Taft told the Boston audience, "I do not want to fight Theodore Roosevelt, but sometimes a man in a corner fights. I am going to fight." At Boston, Taft raised the third term issue, concerned that Colonel Roosevelt "should not have as many terms as his natural life will permit." Ironically, it was just this issue which was responsible for a foiled assassination attempt of Roosevelt by a disgruntled New York bartender in October in Milwaukee.

Roosevelt was the first of the two contenders to speak in Middleborough, arriving April 27 , three days before the primary. Roosevelt's stop in Middleborough was part of his second trip to New England since the beginning of April. Interrupting the New England tour was a side journey to Kansas and Nebraska which nearly cost T. R's voice, so strenuous were the speaking engagements. Because of the strain of the tour, Roosevelt knew it would be futile to mount a full-scale railroad car campaign when he returned to New England at the end of April. "It is folly to try to make me continue a car-tail campaign," he said. Consequently, Roosevelt scheduled appearances only at Fall River, New Bedford and Boston for the morning and evening of the 27th. Due to the efforts of the local Roosevelt Club, however, the itinerary was altered to include brief stops in Brockton, Middleborough and Taunton.

Arriving from Brockton one hour before the scheduled arrival time of 12:30, Roosevelt's motorcade of nearly 12 autos dressed with streamers and enormous Roosevelt placards, came to a halt at the Station Street depot. Roosevelt addressed the crowd of approximately 1,500 from his auto.

Frustrating the Colonel's initial attempts to speak, several motors remained annoyingly running, whereupon Roosevelt protested, asserting, "I cannot talk against the hum of industry."

He continued:

It is a pleasure to be in Massachusetts and to ask your support in as clean drawn a fight between the people and the professional politicians as there ever was in history. We who fight as progressive Republicans fight more than a factional or party fight. The people have a right to rule themselves, to bring justice, social and industrial, to all in this nation. I want justice for the big and little man alike, with special privilege to none. I am glad to see you and to fight your fight. Put through next Tuesday in Massachusetts what Illinois and Pennsylvania have done (T. R. swept both of those states' primaries).

...I ask Massachusetts to support us in this campaign, not because it is easy, but because it is hard. I appeal to you because this is the only kind of fight worth getting into, the kind of fight where the victory is worth winning and where the struggle is difficult. Here in Massachusetts, as elsewhere, we have against us the enormous preponderance of the forces that win victory in ordinary political contests.

Upon the conclusion of the Colonel's remarks, the motorcade began to proceed, but was impeded by the crowd, surging towards Roosevelt, anxious to shake his hand. The

Gazette reported "for a minute it appeared that an accident could not be averted." Fortunately, no such accident occurred. Because Roosevelt had not been anticipated to arrive until after noon, workers from the George E. Keith Company shoe plant on Sumner Avenue had only begun trekking over the Center Street railroad bridge at noon when they came upon the departing hero, who graciously stopped and shook nearly 100 hands. Roosevelt then departed for Taunton, escorted by Spanish-American War veterans and Mayor Fish of the city.

Two days later, on Monday, April 29, one day before the primary, President Taft arrived in a special train in Middleborough at 12:30 to speak before a crowd estimated at 2,000. It is extremely doubtful that Taft would have stopped in town had it not been for Roosevelt's presence a few days earlier. Despite the large crowd, the president was, according to the

Gazette, "rather coolly received, there being but a faint cheer." Taft was introduced to the crowd by Town Republican Committee Chairman George W. Stetson. Still reeling from an address made by Roosevelt on April 3 in Louisville, Kentucky, making much of the Republican bosses' support for Taft, the president was clearly on the defensive in Middleborough:

Ladies and Gentlemen. I am very sorry to take up your time to listen to a voice nearly gone. I come here from a strong sense of duty. It does not make any real difference to me whether I am re-elected President or not so far as my comfort and happiness and reputation are concerned. I fancy, after having had three years' experience in the Presidency, I could find softer and easier places than that, and I am willing to trust to the future for vindication of my name from the aspersions upon it ... (but) if I permit attacks unfounded upon me, I go back on those whom I am leading in that cause (of progress).

Therefore, I have come here, I cannot help it, and I have got to look into your eyes and tell you the truth as near as know it.

It is said that all the bosses are supporting me. I deny it. Mr. Roosevelt and I are exactly alike in certain respects, a good deal of human nature in both of us and when we are running for office we do not examine the clothes or the hair or previous condition of anybody that tenders support. But the only way by which he can make true the statement that all the bosses are supporting me and none of the bosses are supporting him but are opposed to him is to give a new definition to "bosses" and that is that every man in politics that is against him is a boss and every man that is for him is a leader.

Following the speech, the train left for Boston amidst cheers as Taft waved a flag. One ironic side note to the Middleborough speech did not bode well for Taft. Upon Taft's arrival, a local man decided to welcome the president with a cheer. "Three cheers for Ted Roosevelt!," he cried. Realizing his gaffe, he quickly corrected himself, "I mean President Taft." Taft, within earshot, remained unruffled. Smiling, he told the would-be cheerleader in his stentorian tone, "Don't make that mistake tomorrow."

Apparently, many Middleborough voters did make just that "mistake," for the primary vote in Middleborough heavily favored Roosevelt. The primary was called to order promptly at 6 a.m. by clerk Chester E. Weston and "voting was immediately in order." Of 635 Middleborough Republicans voting, 406 gave their preferential vote to Roosevelt, 184 to Taft and a dismal 5 to La Follette. The town also voted nearly 3-1 for the slate of Roosevelt delegates.

Of all 13 primaries, the Massachusetts contest witnessed the closest race between Roosevelt and Taft. Taft took 86,722 Massachusetts votes, followed by Roosevelt's 83,099 and La Follette's 2,058. The popular vote notwithstanding, the Massachusetts outcome was indecisive for, though Taft won the preferential by slightly more than 3,500 (technically making him the victor), Roosevelt's slate of 8 at-large delegates trounced Taft's slate by some 8,000 votes. Roosevelt, perhaps a little disparagingly, wrote his friend, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts: "Well, isn't the outcome in Massachusetts comic? Apparently there were about 80,000 people who preferred Taft, about 80,000 who preferred me and from three to five thousand who, in an involved way, thought they would vote both for Taft and me!"

The final primary was held the first week of June. Of the 13, Roosevelt won nine, losing Wisconsin and North Dakota to La Follette and his native New York and Massachusetts to Taft. As a consequence, Roosevelt received 278 delegates, Taft 48 and La Follette 36.

Because of his victory in the primaries, Roosevelt could joke about the skewed Massachusetts results, but the Massachusetts outcome would cause further clamor at the Republican convention held in Chicago, June 18-22. At Chicago, Taft hoped his control of the National Committee and the southern delegations (whose states did not hold primaries) would offset Roosevelt's popularity.

The first order of convention business was to elect a temporary chairman and the Massachusetts delegation split evenly between Taft-backed Elihu Root and Wisconsin Governor Francis E. McGovern, whose backing by Roosevelt was a concession to appease the La Follette forces. Root squeaked by, 558-501, with the vote of each delegate being taken individually. The close vote set the tone for the remainder of the convention, which the Taft forces intended to dominate by denying Roosevelt's disputation of the credentials of some 250 Taft delegates, and which the Roosevelt forces were determined to keep in turmoil.

During the frequent lulls in convention activity, the New Jersey delegation would rise on cue and begin cheering for Roosevelt. T. R.'s young cousin Nicholas Roosevelt would later recall how the New Jersey delegation would generally be followed by the Massachusetts delegation which, in a cheer led by historian and Harvard professor Albert Bushnell Hart, would shout: "Massachusetts 18! Massachusetts 18! Massachusetts 18! Roosevelt first, last and all the time!" (the 18 referring to the state's number of electoral votes).

On Saturday, June22, nominating began with Taft being nominated by fellow Ohioan Warren G. Harding who, by calling Taft "the greatest progressive of the age," must surely have made Roosevelt apoplectic. The only other name place in nomination was that of La Follette.

Though most Roosevelt delegates abstained from voting at the direction of Roosevelt, there were no serious problems until the vote of the Massachusetts delegation was called. The chairman of the delegation responded that the commonwealth "casts all 18 votes for Taft with 18 abstentions." When the tally was questioned, a roll of the individual Massachusetts delegates was called, the first being Frederick Fosdick, pledged to Roosevelt.

Fosdick: Present, but I refuse to vote. (cheering)

Root (silencing the crowd and leaning from the platform): You have been sent here by your state to vote. If you refuse to do your duty, your alternate will be called upon.

Fosdick: No man on God's earth can make me vote in this convention.

Root then made good his threat and called upon Fosdick's alternate who, due to the contradictory primary results in Massachusetts, happened to be a Taft man. Root continued through the Massachusetts delegation, calling each alternate, whereby Taft succeeded in gaining two votes.

Though the convention was not stopped following the interruption, Roosevelt was livid over the Massachusetts outcome. In the July 6 issue of The Outlook, an irate T. R. labelled his former friend and Secretary of State Root a "modern Autolycus, the snapper-up of unconsidered trifles" who "publicly raped at the last moment (two delegates) from Massachusetts."

Roosevelt refused to consider a compromise candidate such as associate Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes (who would lose to Wilson in 1916) or Missouri Governor Herbert S. Hadley. Said Roosevelt: "I'll name the compromise candidate. He'll be me. I'll name the compromise platform. It will be our platform." Subsequently, Taft won the nomination with 561 votes to Roosevelt's 107, La Follette's 41, Iowa Senator Cummins' 17 and Hughes' 2. However, 344 Roosevelt delegates had abstained from voting.

A week later, the Democratic National Convention was convened in Baltimore and today is notable for being as inharmonious as the Republican Convention of the previous week. In contention for the nomination were House Speaker "Champ" Clark of Missouri, New Jersey reform Governor Woodrow Wilson, Senator Judson Harmon of Ohio and House Majority Leader Oscar Underwood of Alabama. Later in the balloting, the name of Massachusetts Governor Eugene N. Foss, to whom the majority of Massachusetts delegates were pledged, was put forth, but the momentum had already begun to swing towards Wilson, who was selected on the 46th ballot. The selection of Wilson relieved many delegates who had from the start been opposed to Clark, embarrassed by his testimonial for Electric Bitters: "It seemed that all the organs in my body were out of order, but three bottles of Electric Bitters made me all right."

The following month, Roosevelt formally bolted the Republican Party to form the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party which took its nickname from the Colonel's statement that he was "as fit as a bull moose." The Progressive platform called for workmen's compensation, minimum wages for women, the establishment of a federal regulatory commission in industry and the prohibition of child labor. The party was financed, in part, by George W. Perkins, a partner in the House of Morgan, who became known as the "Dough Moose." Taft, too, had financial difficulties. When the Republican National Committee made it known that it once again expected the President's elder half-brother Charley to pick up the tab, Charley Taft protested, "I am not made of money!"

When it was suggested that Taft and Roosevelt cooperate to prevent a Democratic victory, T. R. responded, "I hold that Mr. Taft stole the nomination, and I do not feel like arbitrating with a pickpocket as to whether or not he shall keep my watch."

The 1912 presidential election in Middleborough was basically a repetition of the primary. Though Roosevelt won Middleborough, he lost the state to Wilson. Of 1,358 votes in Middleborough's two precincts, Roosevelt received 545 votes; Wilson sneaked into second place with 378 votes ahead of Taft with 360 votes. Roosevelt, however, was unable to carry the state and, in fact, finished third behind Taft. In total, Wilson won 40 states, Roosevelt six and Taft two.

Whether it was favoritism for Roosevelt or a genuine progressive Republican impulse in Middleborough, the town favored Progressive Party candidates in 7 of 13 races on the ballot in 1912, giving progressive candidates the town's first vote for president, governor, lieutenant governor secretary of state, state treasurer, 2nd Plymouth District senator (Alvin C. Howes of Middleborough) and Plymouth County commissioner (Lyman P. Thomas of Middleborough).

However, in the long run, progressive Republicanism fared badly, both in Middleborough and the nation as a whole. Though the 1913 elections saw Middleborough give its first place vote to eight progressives in 13 races, it was beginning to lose influence to the Republican Party which began to re-absorb its lost members. In fact, in a three-way race in 1913 for the 7th Plymouth District between Middleborough residents Charles N. Atwood (R), Stephen O'Hara (D) and Lyman P. Thomas (P), Thomas finished third, an indication of progressivism's waning appeal. Running for the same position in 1914, Thomas was the only Progressive candidate on the ballot not to be relegated to a third place finish by the Middleborough voters. In fact, the 1914 elections saw few Progressives run and they even failed to contest the gubernatorial race. Many Bull Moose Progressives not rejoining the Republican Party in 1914 found solace in such candidates as progressive-minded David I. Walsh, the successful-Democratic candidate for governor in 1914 and 1915.

Roosevelt's declination of the 1916 Progressive presidential nomination and his endorsement of fence-straddling Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes effectively mended the breach between Republicans and Bull Moose Progressives. In the 1916 elections, Middleborough voted overwhelmingly for Hughes, who received 743 votes to Wilson's 476. The Democratic share of the 1916 Middleborough vote, however, was nearly 35% greater that the Democratic share in 1912, while the Republican share was down 12.5% from the combined Republican-Progressive share of 1912, an indication that many Middleborough Bull Moose Progressives had moved to the Democratic Party by 1916.

In a fitting epitaph for Bull Moose Progressivism, Roosevelt wrote James R. Garfield, son of President Garfield and Roosevelt's secretary of the interior: "We have fought the good fight, we have kept the faith and have nothing to regret."

Click here to hear Roosevelt's "Progressive Covenant with the People" address. Photograph and audio recording courtesy of the Library of Congress. Captioned by Michael J. Maddigan.

Illustrations:

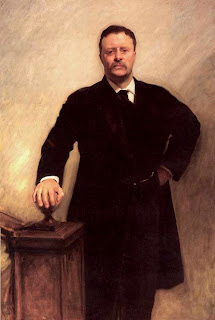

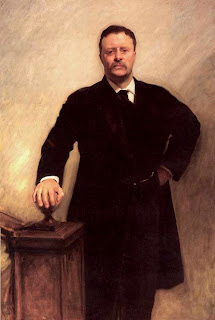

Theodore Roosevelt by John Singer Sargent, oil on canvas, 1903

"Progressive Fallacies", unidentified political cartoon, 1912

In this cartoon from the 1912 presidential election, Theodore Roosevelt has usurped the progressive mantle from Wisconsin senator Robert M. LaFollette who sits sulking on a nearby sofa. Roosevelt is accompanied on the piano by Miss Insurgency, who's contention that Roosevelt sings better than LaFollette was refelctive of the Republican rank and file's view of the former President.

Theodore Roosevelt campaigning, photograph, 1912, courtesy Library of Congress

William Howard Taft, photograph, 1908, courtesy Library of Congress

William Howard Taft, Middleborough, MA, halftone from a photograph taken April 27, 1912

Standing to the left of Taft is George W. Stetson, Middleborough Town Republican Committee Chairman.

"Floor-Manager Taft" by Edward Windsor Kemble, Harper's Weekly, February 12, 1912, pp. 14-15

In this political cartoon, Roosevelt tries to do the "Grizzly Bear" with the "dear old lady" otherwise known as the Republican Party. The cartoon is indicative of the disruption Roosevelt caused in the 1912 Republican campaign.

Plymouth and Barnstable Counties had the highest percentage of votes in Massachusetts for Roosevelt.

On May 22, 1856, Representative Preston S. Brooks of South Carolina brutally assaulted Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner in the Senate chamber. Prompted by a recent anti-slavery speech by Sumner which was harshly critical of the South, Brooks mercilessly beat Sumner into unconsciousness with a gutta percha cane. The shocking brutality of the action further polarized the nation which at the time was riven by the controversy over whether to admit Kansas as a free or slave state, as well as the overall debate on slavery which was becoming increasingly violent. While lauded as a hero in the South, Brooks was villified in the North.

On May 22, 1856, Representative Preston S. Brooks of South Carolina brutally assaulted Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner in the Senate chamber. Prompted by a recent anti-slavery speech by Sumner which was harshly critical of the South, Brooks mercilessly beat Sumner into unconsciousness with a gutta percha cane. The shocking brutality of the action further polarized the nation which at the time was riven by the controversy over whether to admit Kansas as a free or slave state, as well as the overall debate on slavery which was becoming increasingly violent. While lauded as a hero in the South, Brooks was villified in the North.  We do not think that pelting and burning an effigy is so barbarous as the beating of a real live man and still we think there are more effective modes of rebuking sin.

We do not think that pelting and burning an effigy is so barbarous as the beating of a real live man and still we think there are more effective modes of rebuking sin.

+of+Smoky+Mountains+018.jpg)