Saturday, December 24, 2011

Christmas, 1940

In 1940, Middleborough High School Latin teacher Herbert Wilber decorated his classroom with greenery over the chalkboard and a small lighted white pine tree set on a table in the corner. The simple but effective decorations provided a warm and inviting aspect to the otherwise austere classroom. The room was located on the top floor of Middleborough High School, now the Early Childhood Education Center, on North Main Street.

Friday, December 23, 2011

The Stories in the Stones: Reverend Sylvanus Conant

I am pleased to offer the following post by Middleborough educator Jeff Stevens as part of an on-going series written for the Middleboro Gazette on behalf of the Friends of Middleborough Cemeteries. Mr.Stevens is well versed in the history of Middleborough's early cemeteries, and his "The Stories in the Stones" series proposes to consider the rich cultural and social heritage contained within Middleborough's historic cemeteries through the stories of some of those interred within them. It is hoped to post additional stories here as they are written. To learn more about the Friends of Middleborough Cemeteries, or how you can help, click on the icon at the end of the post.

Middleborough’s cemeteries are full of stories. The men and women who founded this town and lived here over the last 300 plus years have left us thousands of gravestones to mark their final resting places. Each stone is often the final sign of the person’s existence. Some exploring in our many historic sources help fill us in on the life stories behind the stones.

The Rev. Silvanus Conant has a large slate stone in the right front section of the Church on the Green Cemetery. He is pictured in his clerical collar, with two angels looking down on him. The stone tells you that he was a “truly evangelic minister” and an “amiable pattern of charity in all its branches”. It then says he died of the smallpox and is buried three miles away. Beside his gravestone is one for his wife, Abigail, who died at age 28 and beside her, a stone for their son, Ezekiah, who died at just seven days old. Is there more to his story?

The History of the Town of Middleboro by Thomas Weston tells us that Rev. Conant was a Harvard grad who was called to be the 4th minister of the Church on the Green after years of congregational infighting between the “New Lights” and the “Old Lights”, conservative and liberal elements. Conant united the two sides and was well loved by his congregation. Judge Peter Oliver attended this church, as did colonial Governors Hutchinson and Bowdoin. Benjamin Franklin visited one Sunday. A contemporary said of him, “He was full of sunshine, radiant with hope, trusting in his God, and believing in man.”

The Rev. Conant was an avid patriot in the time leading up to the American Revolution. He served as a chaplain in a patriot regiment and his inspiring words led to 35 church members volunteering for service.

In 1777-78, Middleborough was struck by the pestilence when smallpox swept into town. The Rev. Conant and eight of his flock died at the “pest house” in the Soule neighborhood and all nine have stones in the Soule Street Smallpox Cemetery on the corner of Soule and Brook Streets. His stone says that he died in “the 58th year of his age and the 33rd of his ministry”. Silvanus Conant may be the only person buried in Middleborough with two gravestones. Thomas Weston reports, “It is said that upon his death there was weeping in every house in town, at the loss of one of their best and dearest friends.” Not a bad legacy for a dedicated minister and enthusiastic American patriot and quite a story behind his two gravestones.

THE STORIES IN THE STONES - The Rev. Silvanus Conant

Jeff Stevens - Friends of Middleborough Cemeteries

Middleborough’s cemeteries are full of stories. The men and women who founded this town and lived here over the last 300 plus years have left us thousands of gravestones to mark their final resting places. Each stone is often the final sign of the person’s existence. Some exploring in our many historic sources help fill us in on the life stories behind the stones.

The Rev. Silvanus Conant has a large slate stone in the right front section of the Church on the Green Cemetery. He is pictured in his clerical collar, with two angels looking down on him. The stone tells you that he was a “truly evangelic minister” and an “amiable pattern of charity in all its branches”. It then says he died of the smallpox and is buried three miles away. Beside his gravestone is one for his wife, Abigail, who died at age 28 and beside her, a stone for their son, Ezekiah, who died at just seven days old. Is there more to his story?

The History of the Town of Middleboro by Thomas Weston tells us that Rev. Conant was a Harvard grad who was called to be the 4th minister of the Church on the Green after years of congregational infighting between the “New Lights” and the “Old Lights”, conservative and liberal elements. Conant united the two sides and was well loved by his congregation. Judge Peter Oliver attended this church, as did colonial Governors Hutchinson and Bowdoin. Benjamin Franklin visited one Sunday. A contemporary said of him, “He was full of sunshine, radiant with hope, trusting in his God, and believing in man.”

The Rev. Conant was an avid patriot in the time leading up to the American Revolution. He served as a chaplain in a patriot regiment and his inspiring words led to 35 church members volunteering for service.

In 1777-78, Middleborough was struck by the pestilence when smallpox swept into town. The Rev. Conant and eight of his flock died at the “pest house” in the Soule neighborhood and all nine have stones in the Soule Street Smallpox Cemetery on the corner of Soule and Brook Streets. His stone says that he died in “the 58th year of his age and the 33rd of his ministry”. Silvanus Conant may be the only person buried in Middleborough with two gravestones. Thomas Weston reports, “It is said that upon his death there was weeping in every house in town, at the loss of one of their best and dearest friends.” Not a bad legacy for a dedicated minister and enthusiastic American patriot and quite a story behind his two gravestones.

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Middleboro Laundry

If one believes this wonderfully dated piece of advertising from the Middleboro Laundry, the local 1950s housewife "broke her heart" trying to iron the perfect dress shirt for her hard to please husband. In despair, she no doubt turned to the services of the Middleboro Laundry. Here her husband scrutinizes the work to ensure it is up to his exacting standards while in the meantime enjoying a cigarette (which rests in an ashtray near his left hand). Compare this with a circa 1880 Victorian trade card from the George H. Doane Hardware Company and you will see that the lot of women had changed little in the intervening 75 years.

The Middleboro Laundry succeeded Swift's Wet Wash Laundry in 1925 and was owned after 1926 by John Grantham. Located on Wareham Street at the Nemasket River, the firm operated throughout the mid-twentieth century as Middleborough's leading laundry.

Illustration:

Middleboro Laundry, Middleborough, MA, ink blotter, mid-20th century

Thursday, December 1, 2011

Book Signing at Somethin's Brewin' Book Cafe

Join me this Saturday from 10 a. m. to 11.45 a. m. at Somethin's Brewin' Book Cafe in Lakeville where I will be signing copies of South Middleborough: A History.

Illustration:

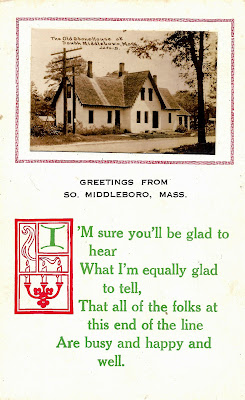

"The Old Stone House", real photo postcard, c. 1920

This postcard features a small photograph of the distinctive Stone House at South Middleborough. Long a landmark in the South Middleborough community, the Stone House was named for the material used in its construction.

The Work of the Victorian Constable

Though Middleborough’s law enforcement agents prior to the reorganization of the Middleborough Police Department in 1909 may have been virtually preoccupied with cases of liquor law violations as noted in the two previous posts, other crimes were on the constabulary’s agenda, as well.

As with liquor laws, there remained a strong social imperative to prosecute laws based upon public morality. Thanks to the efforts of organizations such as the Law & Order League, and others, Middleborough’s Victorian police force engaged in maintaining the sacredness of the Sabbath through enforcement of Sunday “blue laws”. In 1881, the Middleboro Gazette somewhat tongue-in-cheek called for the establishment of a day police, “as employment can be furnished in the way of looking after boys, especially on the Sabbath. ‘The woods are full of ‘em.’” One of Herbert L. Leonard’s first actions as Chief of Police in May, 1901, was to notify local lunch counter operators that they would be required to remain closed on Sundays, prompting one local newspaper to ask “where can a visitor get something to eat on the Sabbath when it is past dinner time at the hotels?”

(Ironically, however, in January, 1886, when local constables arrested a local member of the Salvation Army “for disturbing the peace by playing the hallelujah organ in the street”, Judge Vaughan quickly dismissed the case upon the grounds that the gentleman “had disturbed no one to such an extent as to warrant his holding the defendant for trial”).

(Ironically, however, in January, 1886, when local constables arrested a local member of the Salvation Army “for disturbing the peace by playing the hallelujah organ in the street”, Judge Vaughan quickly dismissed the case upon the grounds that the gentleman “had disturbed no one to such an extent as to warrant his holding the defendant for trial”).

Despite this preoccupation with the enforcement of public morality laws, the early Middleborough police grappled with more serious crimes, most commonly burglary and horse thievery.

Burglaries occurred throughout the period preceding 1909 with the most notorious being the robbery of the town safe in 1871. A string of burglaries occurring in the years around 1880 prompted many residents to arm themselves, and a mini-boom in the sale of firearms was noted in May, 1880. One of those arming himself was grocer Ira Tinkham who in the fall of 1882 used his weapon to fire upon an intruder. In November, 1887, a North Middleborough resident similarly fired upon suspected hen thieves who “left hurriedly.”

The increased number of guns in homes, however, would create its own issues as reported by the local press in January, 1888. “One of the ‘didn’t-know-it-was-loaded’ idiots lives at North Middleboro and one day last week let his gun go off in the sitting room of his house, much to the damage of his furniture and fright of the other occupants of the building. No one was hit by the shot.”

Yet another series of high profile burglaries during the winter of 1885-86 further unsettled the community, particularly following the invasion of elderly Hartley Wood’s home by masked burglars who tied up Wood and his sister while burglarizing the home. So reprehensible was the crime that Middleborough Selectmen offered a $500 reward for the capture and conviction of the perpetrators.

Another frequent crime was that of horse thieving which appears to have peaked during the mid-1880s when Selectmen offered another substantial $500 reward for information leading to the conviction of an unknown horse thief then active in town. “…The town fathers propose to break up the stealing business because it is in their power to do so.” Despite the reward, little concrete information was forthcoming, and the summer of 1887 witnessed a number of horse thefts affecting “several of the well-to-do farmers” in town, including Eleazer Thomas at Rock. Horse thieving would remain a fairly common crime during this era, though occasional lulls in such criminal activity were noted as in June, 1889.

Petty crimes were part of the local constabulary’s work, as well. In October, 1889, the Muttock schoolhouse was ransacked. “The vandals, if detected, ought to be turned over to the tender mercies of the scholars for about an hour,” commented the local newspaper.

Flower thieves struck during the summer of 1885, stealing plants and returning them at night, leading the Middleboro News to quip, “If the party who stole the geranium and pot from Center Street a few nights since, will call at the house, they can have the saucer belonging to the pot.” Similarly, fruit thieves were noted during the autumns of 1885 and 1887, stealing barrels of apples and vegetables left untended overnight.

Clothes were stolen from clotheslines at North Middleborough (February, 1887) and elsewhere (February, 1890), including the family washes of Edward O. Parker and Charles E. Leonard. Meanwhile, Titicut boys were discovered tipping over stone walls and turning out street lamps (“and storing up legal difficulties for themselves”).

Clothes were stolen from clotheslines at North Middleborough (February, 1887) and elsewhere (February, 1890), including the family washes of Edward O. Parker and Charles E. Leonard. Meanwhile, Titicut boys were discovered tipping over stone walls and turning out street lamps (“and storing up legal difficulties for themselves”).

Because late 19th century convention held that “peddlers are nuisances, sometimes thieves, and frequently sell their customers rather than the goods”, itinerant salesmen were the frequent subjects of police observation. Middleborough generally took a firm approach towards unlicensed peddlers, ordering them out of town. Tramps were more often than not treated in a similar fashion.

More serious and more violent crimes were fortunately uncommon. Though incendiarism, or arson, was a rare occurrence, in 1875, an arsonist was believed to be at work. One local newspaper’s advice: “Shoot him.” Domestic violence was not unknown, with cases noted in March, 1886, and April, 1904.

The most serious threat to local law and order, however, came in 1903 with the Independence Day rioting of that year, during which Deputy Sheriff Everett T. Lincoln was shot in the face and Night Watchman George Hatch was forced to flee before a rampaging mob. The town was ultimately charged $455 “for police work in connection with the alleged celebration”, a princely sum in those days. District Court Judge Kelly who presided over the initial trial of nine defendants implicated in the rioting, took a hardline approach and suggested that “if the officers had sprinkled the town house steps with a few prostrate bodies from the crowd, they would have done the right thing.” Middleborough residents initially agreed, though once the sentences were to be handed down, many urged clemency for the convicted rioters.

While the 1903 riots greatly disturbed the community, they ultimately contributed to helping reform the system of local police protection. Six years after the riots, the administration of the Middleborough Police Department would be officially reorganized in 1909, and it is from that time that the modern Middleborough Police Department is said to date.

Illustrations:

"The Norwich Citadel Concertina Band", picture postcard (detail), c. 1907.

Concertinas were popular instruments in the early Salvation Army movement as seen in this photograph of a Salvation Army band based in Norwich, England. In 1886 when Middleborough constables arrested a Salvation Army member for playing a "hallelujah organ" in the streets, the instrument in question was undoubtedly a concertina. Judge Francis M. Vaughan found the disruption caused by the concertina playing did not warrant the defendant's arrest and he dismissed the case.

"Pegs", photograph by donnamarinje, July 27, 2007, republished under a Creative Commons license.

As with liquor laws, there remained a strong social imperative to prosecute laws based upon public morality. Thanks to the efforts of organizations such as the Law & Order League, and others, Middleborough’s Victorian police force engaged in maintaining the sacredness of the Sabbath through enforcement of Sunday “blue laws”. In 1881, the Middleboro Gazette somewhat tongue-in-cheek called for the establishment of a day police, “as employment can be furnished in the way of looking after boys, especially on the Sabbath. ‘The woods are full of ‘em.’” One of Herbert L. Leonard’s first actions as Chief of Police in May, 1901, was to notify local lunch counter operators that they would be required to remain closed on Sundays, prompting one local newspaper to ask “where can a visitor get something to eat on the Sabbath when it is past dinner time at the hotels?”

(Ironically, however, in January, 1886, when local constables arrested a local member of the Salvation Army “for disturbing the peace by playing the hallelujah organ in the street”, Judge Vaughan quickly dismissed the case upon the grounds that the gentleman “had disturbed no one to such an extent as to warrant his holding the defendant for trial”).

(Ironically, however, in January, 1886, when local constables arrested a local member of the Salvation Army “for disturbing the peace by playing the hallelujah organ in the street”, Judge Vaughan quickly dismissed the case upon the grounds that the gentleman “had disturbed no one to such an extent as to warrant his holding the defendant for trial”).Despite this preoccupation with the enforcement of public morality laws, the early Middleborough police grappled with more serious crimes, most commonly burglary and horse thievery.

Burglaries occurred throughout the period preceding 1909 with the most notorious being the robbery of the town safe in 1871. A string of burglaries occurring in the years around 1880 prompted many residents to arm themselves, and a mini-boom in the sale of firearms was noted in May, 1880. One of those arming himself was grocer Ira Tinkham who in the fall of 1882 used his weapon to fire upon an intruder. In November, 1887, a North Middleborough resident similarly fired upon suspected hen thieves who “left hurriedly.”

The increased number of guns in homes, however, would create its own issues as reported by the local press in January, 1888. “One of the ‘didn’t-know-it-was-loaded’ idiots lives at North Middleboro and one day last week let his gun go off in the sitting room of his house, much to the damage of his furniture and fright of the other occupants of the building. No one was hit by the shot.”

Yet another series of high profile burglaries during the winter of 1885-86 further unsettled the community, particularly following the invasion of elderly Hartley Wood’s home by masked burglars who tied up Wood and his sister while burglarizing the home. So reprehensible was the crime that Middleborough Selectmen offered a $500 reward for the capture and conviction of the perpetrators.

Another frequent crime was that of horse thieving which appears to have peaked during the mid-1880s when Selectmen offered another substantial $500 reward for information leading to the conviction of an unknown horse thief then active in town. “…The town fathers propose to break up the stealing business because it is in their power to do so.” Despite the reward, little concrete information was forthcoming, and the summer of 1887 witnessed a number of horse thefts affecting “several of the well-to-do farmers” in town, including Eleazer Thomas at Rock. Horse thieving would remain a fairly common crime during this era, though occasional lulls in such criminal activity were noted as in June, 1889.

Petty crimes were part of the local constabulary’s work, as well. In October, 1889, the Muttock schoolhouse was ransacked. “The vandals, if detected, ought to be turned over to the tender mercies of the scholars for about an hour,” commented the local newspaper.

Flower thieves struck during the summer of 1885, stealing plants and returning them at night, leading the Middleboro News to quip, “If the party who stole the geranium and pot from Center Street a few nights since, will call at the house, they can have the saucer belonging to the pot.” Similarly, fruit thieves were noted during the autumns of 1885 and 1887, stealing barrels of apples and vegetables left untended overnight.

Clothes were stolen from clotheslines at North Middleborough (February, 1887) and elsewhere (February, 1890), including the family washes of Edward O. Parker and Charles E. Leonard. Meanwhile, Titicut boys were discovered tipping over stone walls and turning out street lamps (“and storing up legal difficulties for themselves”).

Clothes were stolen from clotheslines at North Middleborough (February, 1887) and elsewhere (February, 1890), including the family washes of Edward O. Parker and Charles E. Leonard. Meanwhile, Titicut boys were discovered tipping over stone walls and turning out street lamps (“and storing up legal difficulties for themselves”). Because late 19th century convention held that “peddlers are nuisances, sometimes thieves, and frequently sell their customers rather than the goods”, itinerant salesmen were the frequent subjects of police observation. Middleborough generally took a firm approach towards unlicensed peddlers, ordering them out of town. Tramps were more often than not treated in a similar fashion.

More serious and more violent crimes were fortunately uncommon. Though incendiarism, or arson, was a rare occurrence, in 1875, an arsonist was believed to be at work. One local newspaper’s advice: “Shoot him.” Domestic violence was not unknown, with cases noted in March, 1886, and April, 1904.

The most serious threat to local law and order, however, came in 1903 with the Independence Day rioting of that year, during which Deputy Sheriff Everett T. Lincoln was shot in the face and Night Watchman George Hatch was forced to flee before a rampaging mob. The town was ultimately charged $455 “for police work in connection with the alleged celebration”, a princely sum in those days. District Court Judge Kelly who presided over the initial trial of nine defendants implicated in the rioting, took a hardline approach and suggested that “if the officers had sprinkled the town house steps with a few prostrate bodies from the crowd, they would have done the right thing.” Middleborough residents initially agreed, though once the sentences were to be handed down, many urged clemency for the convicted rioters.

While the 1903 riots greatly disturbed the community, they ultimately contributed to helping reform the system of local police protection. Six years after the riots, the administration of the Middleborough Police Department would be officially reorganized in 1909, and it is from that time that the modern Middleborough Police Department is said to date.

Illustrations:

"The Norwich Citadel Concertina Band", picture postcard (detail), c. 1907.

Concertinas were popular instruments in the early Salvation Army movement as seen in this photograph of a Salvation Army band based in Norwich, England. In 1886 when Middleborough constables arrested a Salvation Army member for playing a "hallelujah organ" in the streets, the instrument in question was undoubtedly a concertina. Judge Francis M. Vaughan found the disruption caused by the concertina playing did not warrant the defendant's arrest and he dismissed the case.

"Pegs", photograph by donnamarinje, July 27, 2007, republished under a Creative Commons license.

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

The Early Middleborough Police Department and Liquor Laws

Mertie Romaine notes of the Middleborough Police Department in her History of the Town of Middleboro that as late as 1909, “the constables were devoting their attention almost entirely to enforcing liquor laws.” The early Middleborough Police Department’s preoccupation with the enforcement of such laws was the consequence of a strong social and moral imperative within the community which sought to combat public drunkenness during the last quarter of the 19th century and beyond. The Middleborough constabulary which then was emerging as a modern police force was regarded by local temperance leaders as the perfect vehicle to enforce temperance laws and exhibit the community’s moral conscience.

During the mid and late 19th century, temperance (the moderation or total abstinence from drinking alcohol) became not only a powerful social movement, but a political one as well. Locally, temperance organizations such as the Sons of Temperance, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Good Templars all promoted the temperance cause and were supported politically in their struggle by the Prohibition Party, led locally by undertaker George Soule. Not only did these organizations generally oppose the consumption of liquor, but they supported the criminalization of its sale as well.

The temperance groups were able to wield considerable influence within the community, so much so that prior to the close of the 1874-75 school year, total abstinence pledges “binding the signers to abstain from the use of alcoholic stimulants and tobacco in any form” were freely circulated in the Middleborough public schools.

The temperance groups were able to wield considerable influence within the community, so much so that prior to the close of the 1874-75 school year, total abstinence pledges “binding the signers to abstain from the use of alcoholic stimulants and tobacco in any form” were freely circulated in the Middleborough public schools.

Undoubtedly the pledges were a response to what the community saw as a resurgence in intemperance with the Middleboro Gazette complaining at the start of the year of the rise in public drunkenness. As if to corroborate the claim, 16 men were subsequently brought before the district court and charged with public drunkenness and engaging “in a free fight with knives, clubs, fists and pistols.”

The crack down on liquor law violators was stepped up during the 1880s simultaneous with the local constabulary’s growth and evolution as a modern police force. In conjunction with the temperance organizations, the Law and Order League, established in 1884 as a predecessor of the Committee to Suppress Crime and active through at least the end of the decade, focused nearly exclusively upon moral issues. Within months of its foundation, the League could claim that whereas in 1882 there had been 20 local liquor dealers in town, by March, 1885, there were none.

Liquor law violations and public drunkenness were considered grave matters at the time and the League consequently supported an aggressive prosecution of the community’s liquor laws. Convictions were frequent, and the sentences meted out harsh. In mid-1887, provisions dealer Randall Hathaway, “a prominent business man of Middleboro”, was sentenced to six months in the county house of correction for public drunkenness. In October of that same year, Michael Monihan, who “got crazy drunk and was smashing up his household effects”, was fined $5 and costs. Undoubtedly, the private nature of Monihan’s indiscretion saved him from a lengthy prison stint.

Throughout the 1880s, operators of local saloons and the bar tenders they employed were the frequent object of police attention, thanks largely to the influence of the Law and Order League. The most notorious and flagrant violator of local liquor laws was Stephen O’ Hara, operator of a bar room on Wareham Street near the Four Corners, who along with his bar tenders “occupied conspicuous places at the last two terms of the Superior Court” in 1887 and 1888.

Convicted in March, 1888, for keeping a “liquor nuisance”, O’Hara “slipped his bail and was supposed to have skipped the state” prior to his October sentencing hearing before the Superior Court. He was later arrested tending bar at Boston and conveyed to Taunton where he was held in a room in the City Hotel. From his hotel room, O’Hara shimmied down a drainpipe and escaped, “taken away in a carriage by friends who conveyed him out of the state” in the summer of 1889. Though one of the witnesses in the O’Hara case alleged that the defendant had offered him a bribe and subsequently threatened bodily harm when the bribe was refused, O’Hara finally agreed to appear in court in December, 1889, and settled all claims against him, acknowledging “that the Law and Order League had beaten him.” Nonetheless, it would not be the last of O’Hara’s encounters with the law.

The local constabulary’s relentless pursuit of liquor law transgressors sometimes brought retaliation from defendants who sought to create legal issues for Middleborough constables. In July, 1890, Stephen B. Young, convicted of the illegal sale of liquor and keeping a liquor nuisance at his barbershop brought legal suit against the Middleborough constables for wrongful arrest in an incident unrelated to his liquor law conviction, seeking damages of $5,000. “Middleboro constables are in warm water and Stephen B. Young is poking up the fire below them,” reported the local press.

Similarly, Stephen O’ Hara was back in the news in September, 1903, when he was arrested with 12 pints of whiskey in his possession. O’Hara was charged with the illegal transportation of liquor in a no-license town, but the charges were ultimately dropped by Judge Nathan Washburn who contended that there was no proof that O’Hara actually intended to sell the alcohol. Like Young before him, O’Hara subsequently brought suit against Officer William A. Green of the Committee for the Suppression of Crime, one of the arresting officers.

For over 35 years, the Middleborough Police remained preoccupied with the enforcement of the community’s liquor laws. Following the crackdown upon local saloons, attention was directed following 1900 to the town’s hotels, primarily the Central Inn and the Linwood House on Center Street, which were constantly (and successfully) raided for liquor-related violations.

Eventually, with the decreasing political influence of the temperance movement, the Middleborough Police’s preoccupation with liquor law enforcement came to be seen as verging on monomania, the butt of not infrequent jokes. During the summer of 1901, after a spate of false fire alarms occurred following the installation of glass-fronted key boxes at and about the Four Corners, the Plymouth Old Colony Memorial quipped that “someone ought to rub a little rum on the alarm pullers, and then perhaps the Middleboro police, so successful at liquor raids, can perhaps catch them.”

Ultimately, the attention given to liquor law enforcement would evaporate for a number of reasons, including the waning strength of the temperance movement, the decision of the community to permit liquor licensing and the rise in other, more serious crimes, which forced attention elsewhere. These developments, as well as the growing reaction with the constabulary’s liquor law obsession would ultimately help contribute to the establishment of a reformed modern police organization in town.

Illustration:

Family Temperance Pledge Certificate, late 1800s

Such decorative temperance pledge certificates for families, individuals and schoolchildren were common in the mid and late 1800s and pledged the subscriber to abstain from the consumption of alcohol as well as tobacco. The generally widespread support for temperance encouraged the Middleborough constabulary to direct much of its attention to violators of local liquor laws during the post-bellum period.

During the mid and late 19th century, temperance (the moderation or total abstinence from drinking alcohol) became not only a powerful social movement, but a political one as well. Locally, temperance organizations such as the Sons of Temperance, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Good Templars all promoted the temperance cause and were supported politically in their struggle by the Prohibition Party, led locally by undertaker George Soule. Not only did these organizations generally oppose the consumption of liquor, but they supported the criminalization of its sale as well.

The temperance groups were able to wield considerable influence within the community, so much so that prior to the close of the 1874-75 school year, total abstinence pledges “binding the signers to abstain from the use of alcoholic stimulants and tobacco in any form” were freely circulated in the Middleborough public schools.

The temperance groups were able to wield considerable influence within the community, so much so that prior to the close of the 1874-75 school year, total abstinence pledges “binding the signers to abstain from the use of alcoholic stimulants and tobacco in any form” were freely circulated in the Middleborough public schools.Undoubtedly the pledges were a response to what the community saw as a resurgence in intemperance with the Middleboro Gazette complaining at the start of the year of the rise in public drunkenness. As if to corroborate the claim, 16 men were subsequently brought before the district court and charged with public drunkenness and engaging “in a free fight with knives, clubs, fists and pistols.”

The crack down on liquor law violators was stepped up during the 1880s simultaneous with the local constabulary’s growth and evolution as a modern police force. In conjunction with the temperance organizations, the Law and Order League, established in 1884 as a predecessor of the Committee to Suppress Crime and active through at least the end of the decade, focused nearly exclusively upon moral issues. Within months of its foundation, the League could claim that whereas in 1882 there had been 20 local liquor dealers in town, by March, 1885, there were none.

Liquor law violations and public drunkenness were considered grave matters at the time and the League consequently supported an aggressive prosecution of the community’s liquor laws. Convictions were frequent, and the sentences meted out harsh. In mid-1887, provisions dealer Randall Hathaway, “a prominent business man of Middleboro”, was sentenced to six months in the county house of correction for public drunkenness. In October of that same year, Michael Monihan, who “got crazy drunk and was smashing up his household effects”, was fined $5 and costs. Undoubtedly, the private nature of Monihan’s indiscretion saved him from a lengthy prison stint.

Throughout the 1880s, operators of local saloons and the bar tenders they employed were the frequent object of police attention, thanks largely to the influence of the Law and Order League. The most notorious and flagrant violator of local liquor laws was Stephen O’ Hara, operator of a bar room on Wareham Street near the Four Corners, who along with his bar tenders “occupied conspicuous places at the last two terms of the Superior Court” in 1887 and 1888.

Convicted in March, 1888, for keeping a “liquor nuisance”, O’Hara “slipped his bail and was supposed to have skipped the state” prior to his October sentencing hearing before the Superior Court. He was later arrested tending bar at Boston and conveyed to Taunton where he was held in a room in the City Hotel. From his hotel room, O’Hara shimmied down a drainpipe and escaped, “taken away in a carriage by friends who conveyed him out of the state” in the summer of 1889. Though one of the witnesses in the O’Hara case alleged that the defendant had offered him a bribe and subsequently threatened bodily harm when the bribe was refused, O’Hara finally agreed to appear in court in December, 1889, and settled all claims against him, acknowledging “that the Law and Order League had beaten him.” Nonetheless, it would not be the last of O’Hara’s encounters with the law.

The local constabulary’s relentless pursuit of liquor law transgressors sometimes brought retaliation from defendants who sought to create legal issues for Middleborough constables. In July, 1890, Stephen B. Young, convicted of the illegal sale of liquor and keeping a liquor nuisance at his barbershop brought legal suit against the Middleborough constables for wrongful arrest in an incident unrelated to his liquor law conviction, seeking damages of $5,000. “Middleboro constables are in warm water and Stephen B. Young is poking up the fire below them,” reported the local press.

Similarly, Stephen O’ Hara was back in the news in September, 1903, when he was arrested with 12 pints of whiskey in his possession. O’Hara was charged with the illegal transportation of liquor in a no-license town, but the charges were ultimately dropped by Judge Nathan Washburn who contended that there was no proof that O’Hara actually intended to sell the alcohol. Like Young before him, O’Hara subsequently brought suit against Officer William A. Green of the Committee for the Suppression of Crime, one of the arresting officers.

For over 35 years, the Middleborough Police remained preoccupied with the enforcement of the community’s liquor laws. Following the crackdown upon local saloons, attention was directed following 1900 to the town’s hotels, primarily the Central Inn and the Linwood House on Center Street, which were constantly (and successfully) raided for liquor-related violations.

Eventually, with the decreasing political influence of the temperance movement, the Middleborough Police’s preoccupation with liquor law enforcement came to be seen as verging on monomania, the butt of not infrequent jokes. During the summer of 1901, after a spate of false fire alarms occurred following the installation of glass-fronted key boxes at and about the Four Corners, the Plymouth Old Colony Memorial quipped that “someone ought to rub a little rum on the alarm pullers, and then perhaps the Middleboro police, so successful at liquor raids, can perhaps catch them.”

Ultimately, the attention given to liquor law enforcement would evaporate for a number of reasons, including the waning strength of the temperance movement, the decision of the community to permit liquor licensing and the rise in other, more serious crimes, which forced attention elsewhere. These developments, as well as the growing reaction with the constabulary’s liquor law obsession would ultimately help contribute to the establishment of a reformed modern police organization in town.

Illustration:

Family Temperance Pledge Certificate, late 1800s

Such decorative temperance pledge certificates for families, individuals and schoolchildren were common in the mid and late 1800s and pledged the subscriber to abstain from the consumption of alcohol as well as tobacco. The generally widespread support for temperance encouraged the Middleborough constabulary to direct much of its attention to violators of local liquor laws during the post-bellum period.

Monday, November 28, 2011

The Pre-History of the Middleborough Police Department

While the establishment of the Middleborough Police Department is typically dated to 1909 when Harry W. Swift was named the first Chief of Police, the department in fact has a lengthy pre-history dating back decades prior to 1909 and newspaper accounts attest to the department's early characterization as a police force, as well as the existence of earlier chiefs heading the department.

Constables constituted Middleborough's earliest law enforcement force. Answerable to the Board of Selectmen, constables were responsible for upholding the laws passed by the General Court at Plymouth and later Boston, as well as local by-laws adopted by the community. In contrast to the respect with which law enforcement officials are generally held today, the 18th century constable held a thankless position, one which was frequently fraught with frustration and which involved no financial recompense. Not surprisingly, men usually tried to avoid the duty whenever possible.

Over time, however, the role of the constable within the community grew, particularly in the post-Civil War era when new responsibilities were assumed by the constabulary as the conception of public safety broadened and more and more demands were made for a full-time professional organization. By 1879, Leander M. Alden was not only serving as one of Middleborough's constables, but he was engaged as a special police officer and a truant officer who was also responsible for overseeing the town lock up or jail six nights weekly.

The public's growing concern over law and order matters was motivated by the rapid growth of the community, particularly around Middleborough Four Corners, and a perception of an increasing crime rate and was bolstered by the advocacy of the Middleboro Gazette and the Middleboro News, both of which supported an expanded and strong police force. The attention given local law enforcement concerns was but one aspect of the era's preoccupation with "improvement" which entailed the provision or expansion of municipal services including fire protection, public water and sewerage, gas and electric lighting, telegraphic and telephonic communication and naturally police protection.

The Middleborough constabulary that existed in the nearly half century between the close of the Civil War and 1909 was a force of eight to a dozen men engaged in the maintenance of public safety and order during the day time hours and included men such as James Cole, Samuel S. Lovell, Sylvanus Mendall, Everett T. Lincoln, Benjamin W. Bump, George W. Hammond and John W. Flansburg.

These men, like their colonial predecessors, received little financial remuneration for their efforts though they were reimbursed for out of pocket expenses. Because the men who occupied constabulary positions were not compensated for their duties, they more often than not were employed full-time elsewhere and attention to their law enforcement duties consequently sometimes proved irregular. Additionally, the constabulary's attention was by and large focused upon the downtown district, and rarely extended beyond the outskirts of Midleborough center. Yet despite these criticisms, Middleborough was afforded a level of public safety previously unknown.

More frequently than not, Middleborough's Victorian-era constables were engaged in the prosecution of laws related to the moral purity of the community, being seen especially by temperance leaders within the community as a bulwark against public drunkenness and general moral depravity. Consequently, much of their attention was devoted to the enforcement of local liquor laws. Fortunately, crimes against property such as burglary, larceny and arson (then known as incendiarism) were much less frequent, and violent personal crimes were virtually unknown.

For transgressors of the law, the town provided a lock up which according to one pundit of the era was "one of the most popular places in Middleboro'... It is almost constantly patronized, mostly by hen thieves and fast drivers." Located in the basement of Middleborough Town Hall constructed in 1874, the lock up consisted of brick-walled cells with concrete floors and iron doors. It was cold, damp and unhealthy. The condition of the lock up prompted the editor of the Middleboro News to advocate for its improvement in the summer of 1888, but little change was made and the dank cells remained in use for decades.

An important adjunct to the constabulary was the night watch, a generally lone individual charged with patrolling the community during the overnight hours as a deterrent to criminal activity. Certainly the value of the watch was proven many times over such as in May, 1874, when through the vigilance of the night watchman a potentially devastating fire was discovered and quelled before it could cause much damage. Voters demonstrated their appreciation of the night watch by appropriating the then considerable sum of $50 in 1875 to help fund it. (A decade and a half later, that figure reached several hundred dollars and remained there until formal establishment of the police department in 1909).

So satisfied were downtown residents with the night watch (and wary of nocturnal criminal activity) that they favored its expansion into a nighttime police force, most notably in 1887. These calls however went unheeded. The night watch would continue to operate for decades, in time becoming the most visible aspect of local law enforcement, the image of the sole night watchman on his lonely rounds eclipsing the view of the daytime constabulary in the public's mind. Prominent among Middleborough's night watchmen during this period were George Rich, Herbert L. Leonard and George E. Hatch.

Somewhat naturally, the strong element of protection afforded to the community during the evening hours and the desire for the creation of a night police was reflected in a demand for comparable protection during the day. In 1877 local residents called for the establishment of a permanent police force. Four years later, more specifically, "a day police [was] called for ... by the Middleboro Gazette." While such a police force was not formed, support for the constabulary was maintained and a Committee for the Suppression of Crime was eventually created to provide the local citizenry with a voice in local law enforcement matters. While the committee served a useful purpose in dramatizing the need for a modern police force, it also had the unfortunate result of politicizing public safety issues.

Throughout the last quarter of the 19th century, the Middleborough constabulary continued to evolve, assuming administrative functions and roles that would presage the modern police department. Modernization brought with it, too, a change in the way in which the constabulary was perceived by the public with records indicating that at times prior to 1909, the force of constables was referred to as a "police force" and a "police department". Additionally, the adoption of a modern organizational command structure brought with it the creation of the position of chief of police. As early as 1887 that title was in use, receiving official sanction in 1901 when long-serving constable Herbert L. Leonard was named Chief of Police by the Board of Selectmen.

The most significant step towards modernization, however, came in 1909 when ongoing challenges with the operation of the constabulary system of law enforcement prompted the Board of Selectmen to appoint constable Harry W. Swift to oversee the reorganized force of experienced constables as the modern Middleborough Police Department, thereby inaugurating a new chapter in Middleborough's public safety history.

Illustration:

Middleborough Police Department, Middleborough, MA, photograph, c. 1909

Pictured on the steps of the former Peirce Academy is Middleborough's "first" police department with Chief Harry W. Swift standing front row center. The nine man force was representative of a long tradition of constabulary-based law enforcement in Middleborough as well as a more modern organization and approach to law enforcement which was adopted in 1909.

Monday, November 14, 2011

South Middleborough History

Recollecting Nemasket is pleased to announce the publication of South Middleborough: A History by historian Michael J. Maddigan. Produced by the History Press, a publisher of the highest quality local and regional history titles from coast to coast, South Middleborough is a comprehensive history of the South Middleborough community from its first settlement through the present day. The history is profusely illustrated with over 80 images and maps from the author's personal collection, the Middleborough Historical Association and South Middleborough residents.

Recollecting Nemasket is pleased to announce the publication of South Middleborough: A History by historian Michael J. Maddigan. Produced by the History Press, a publisher of the highest quality local and regional history titles from coast to coast, South Middleborough is a comprehensive history of the South Middleborough community from its first settlement through the present day. The history is profusely illustrated with over 80 images and maps from the author's personal collection, the Middleborough Historical Association and South Middleborough residents. In the late 1700s, settlers flocked to South Middleborough , Massachusetts South Middleborough from its early years, with stories of the contentious ministry of Reverend Ebenezer Jones and the original Hell's Blazes Tavern, into the twentieth century, with memories of Wareham Street South Middleborough and pays tribute to the indomitable spirit of a New England village.

Michael J. Maddigan has been active in the fields of local history and historic preservation for nearly thirty years, and he currently serves as the vice-chairman of the Middleborough Historical Commission. He was responsible for the successful listing of

Michael J. Maddigan has been active in the fields of local history and historic preservation for nearly thirty years, and he currently serves as the vice-chairman of the Middleborough Historical Commission. He was responsible for the successful listing of South Middleborough on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009, much of the research for which forms the basis of South Middleborough : A History. His other works of local history include Images of America Middleborough Rock Cemetery

Michael J. Maddigan has been active in the fields of local history and historic preservation for nearly thirty years, and he currently serves as the vice-chairman of the Middleborough Historical Commission. He was responsible for the successful listing of

Michael J. Maddigan has been active in the fields of local history and historic preservation for nearly thirty years, and he currently serves as the vice-chairman of the Middleborough Historical Commission. He was responsible for the successful listing of Source:

The History Press

To order your copy of South Middleborough: A History today, simply print the order form below, complete, and mail with your payment to the address indicated. (To print, click on the form, then right click and select "print picture").

Friday, November 11, 2011

Soldiers & Sailors Monument, 1896

On May 30, 1896, Middleborough dedicated its impressive Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial on the Town Hall lawn to the memory of the community's civil war veterans. Though the initial proposal for the memorial was met with skepticism and concerns that the monument would be neglected in time, the Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial has since become a focal point of both Memorial and Veterans' Day observances now held at the neighboring Veterans' Memorial Park. At the time of its dedication to "the defenders of our country" in 1896, the Middleboro Gazette published the following brief history of the memorial's origins.

On May 30, 1896, Middleborough dedicated its impressive Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial on the Town Hall lawn to the memory of the community's civil war veterans. Though the initial proposal for the memorial was met with skepticism and concerns that the monument would be neglected in time, the Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial has since become a focal point of both Memorial and Veterans' Day observances now held at the neighboring Veterans' Memorial Park. At the time of its dedication to "the defenders of our country" in 1896, the Middleboro Gazette published the following brief history of the memorial's origins.The first movement looking towards a soldiers’ memorial was soon after the close of the war, when the town made an appropriation of $1000 for a monument, but the matter was overshadowed by the urgent need of a new town house, and was disposed of on that account, and nothing ever came of it. The following item in the MIDDLEBOROUGH GAZETTE of June 9, 1866, perhaps best explains the final disposition of the affair: “A town meeting has been called for the 18th to see what action the town will take in regard to building a Memorial and Town Hall. The town has already voted $1000 towards building a monument, and it is found a much larger sum will be needed to erect a shaft that shall be at all honorable to our people. We are at the same time greatly in need of a decent town house. It is therefore proposed with great unanimity on the part of our heaviest taxpayers to drop the matter of a monument, and erect a good Town and Memorial hall. This building will in the end be much cheaper than to build both; and at the same time, its design as a memorial of the sacrifices of our citizen soldiers, will be secured.” It is evident that though the Town house was finally built, the memorial hall in connection with it failed to materialize.

The first written plea for a monument appeared in the columns of the GAZETTE, from the pen of that gifted writer, so well and favorably known by our townspeople, today, Miss Nellie Brightman, now of Boston, and was probably called forth by the action of the town in regard to the soldiers’ monument, and was published July 7, 1866.

It was an earnest appeal for a distinct soldiers’ memorial, and decried the idea of a combination of a Town and Memorial hall, as will be seen by the following extract: “Can we raise utility to so great a height that sublimity will not become ridiculous in the effort to descend to its level? Does not the idea of commemorating the great deeds of the brave soar beyond and above all thought of earthly use and convenience, carrying the mind away from business, amusements, and the gathering of hundred, onward to the glorious assemblage of our gallant thousands in celestial halls of light?”

We wish we might be able to reproduce the article entire, but the closing sentences are especially fine: “One objection to the shaft is that it will become defaced in time, and will be neglected. A hard commentary on the gratitude of future generations. Will children forget the brave deeds of their fathers? We are lower than the heathen if we cannot educate our children to look with awe and affection on the commemorative stone, and it is especially our duty, which neglected now will never be performed, to institute, theirs to perpetuate, this emblem of the soldier’s valor, and of events that called it forth. Are there ‘none so poor to do them reverence’ – the gallant boys, who full of hope and eager for the fray, left their beautiful village homes to return no more? Don’t give up the monument! Wait, work and hope, and in time see the glorious workmanship arise majestic and grand. Let the sun’s latest rays at his setting gild the half raised visor of the soldier’s cap, and as he slowly sinks behind the hills they loved, let his light play lovingly round the glistening steel of the bayonet, which in the hands of men we venerate, brought back sweet peace to our native land.”

The matter of a monument seems to have languished from this time on with faint attempts to revive it until about 1889, when the first committee was appointed to forward the work and was organized with John C. Sullivan, past Commander of Post 8, as chairman, and W. B. Stetson, then Commander of the Post, as secretary, and George H. Walker, treasurer. Sylvanus Mendall and Alvin C. Howes were the other members of the committee.

From the resignation of J. C. Sullivan and the death of the late George H. Walker, the committee was composed as follows: Alvin C. Howes, chairman, Warren B. Stetson, secretary, Sylvanus Mendall, treasurer, John N. Main and Jairus H. Shaw, which committee continued at the head of the movement. The following were added as a citizens’ committee to co-operate with them in 1894: Joseph E. Beals, Rev. M. F. Johnson, Rev. J. H. O’Neil, Rev. R. G. Woodbridge, Rev. George W. Stearns, David G. Pratt and George W. Stetson, Esq., and this number was augmented by the addition of six more members, Rev. W. F. Davis, George H. Shaw, Hon. M. H. Cushing, Sprague S. Stetson, Henry D. Smith.

Illustration:

"Soldiers Monument, Middleboro, Mass.", F. N. Whitman, Middleborough, MA, publisher, postcard, early 20th century.

Source:

“Soldiers’ Memorial”, Middleboro Gazette, May 30, 1896.

Thursday, November 10, 2011

Six Brothers in War, 1861-65

Locally many may know of the Marra brothers, the sons of Angelo and Josephine Marra, who served their country in World War II. Eighty years earlier, a similarly remarkable contribution had been made by another Middleborough family, the Nickersons, with the service of six of its sons in the Civil War.

Hiram Nickerson (1826-1910) served December 2, 1861-November 1, 1862; Ivory Harlow Nickerson (1829-1920) served December 26, 1861-June 5, 1863; Frederick U. Nickerson (1833-1915) served February 12 1861-June 17, 1865; Maranda R. Nickerson (1838- ) served August 22, 1861-August 27, 1864; James Thomas Nickerson (1844- ) served February 20, 1864-July 16, 1865; and Simeon Leonard Nickerson (c. 1846-1921) served December 16, 1864-May 12, 1865, were the six sons of James and Sylvia Nickerson who did service to their country.

In the collections of the Middleborough Public Library is an unidentified newspaper clipping dating from August 14, 1904. Written by Middleborough newspaperman James H. Creedon, the clipping documents the contributions of the Nickersons during the war:

The record of the six sons of James and Sylvia Nickerson of Middleboro, who bore arms on the union side during the civil war, is one which is rarely equaled.

There were 11 members of the family, nine of whom were boys, and of this number six enlisted under the stars and stripes, and all six returned from the war. One has since died, disease contracted during the war having caused death, but the other brothers are still in fairly good health.

On the call to arms the brothers were interested, as were many of the young men of that period and on their first opportunity the enlisted.

The one who served the longest was Frederick U. Nickerson, now a resident of New Bedford, who enlisted early in the war and remained till the end. His first enlistment was in Co. E, 32d regt, as a private, and when his term had expired he reenlisted, this time with the rank of corporal.

He served in many important battles, including Gainesville, second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Rappahannock station, Wilderness, Spottsylvania, Cold harbor, Petersburg and Appomattox, where he was discharged on account of the close of the war June 17, 1865. He was a member of E. W. Peirce post, G. A. R., of Middleboro for some years, and later transferred to the New Bedford post.

Hiram Nickerson of Middleboro was another brother who went to the front, and after receiving a wound in the second Bull Run was discharged from the service. He enlisted in Co. E of the 32d Mass regt, and after camping at Boston awhile they went to the front. The second Bull Run was the only battle he had an opportunity to participate in. He now resides on Warren av, and is a member of E. W. Peirce post of Middleboro. Mr. and Mrs. Nickerson recently observed their golden wedding anniversary.

The youngest brother of the number is Simeon L. Nickerson, the keeper of the Middleboro poor farm. When less than 18, having secured his parents' consent, he started for the front. This was in 1864, and the young man went out with the 24th regt unattached.

He was in camp some months, but did not have an opportunity to participate in any engagements. Mr. Nickerson is well known in Middleboro, and recently celebrated his silver wedding anniversary. He is a prominent member in the local G. A. R. post.

Ivory Nickerson, the fourth brother, resides at Tremont, where he has a comfortable place. He was with Co D of the 32d Massachusetts regt and was in the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg and the second Bull Run. At Fredricksburg he received an honorable discharge, having been a sufferer from dropsy.

He was employed for several years at the iron works at Tremont, but of late has worked but little. He was a member of the local G. A. R. post, but owing to the inconvenience of attending the sessions he took a demit.

Another brother, James, lives in Rochester. He was the next oldest after Simeon, and he, too, was anxious to get to the front while still in his teens. He served in the 40th regt, participating in several engagements.

The brother who died was Maranda Nickerson. He went out with the 18th Massachusetts regt, but contracted measles while at war, and this brought on consumption. He was discharged and returned home, dying some time later.

It is a notable fact that this family of fighters descended from a fighter, their father, James Nickerson, having served in the war of 1812. He was a member of the crew of a merchant vessel which, after a desperate struggle, was pilfered by a pirate ship commanded by Capt Simms, who, after subduing the crew and burning their boat, landed them on British soil.

The brothers are anxiously anticipating the exercises of encampment week at Boston, and will doubtless participate in the celebration.

In his article Creedon describes the Nickersons as a “family of fighters”, and it should be noted that the family, following 1904 when Creedon was writing, continued to serve their country in the armed forces. Most notable was Hiram Nickerson’s grandson, Simeon L. Nickerson, who was killed in action in World War I. It is for him that Nickerson Avenue and the local American Legion post are named.

Illustration:

"Six Brothers in the War", unidentified newspaper clipping, August 14, 1904, Middleborough Public Library

Friday, October 21, 2011

Autumnal Advertising

Among the most creative business owners when it came to advertising in late 19th century Middleborough was Solomon H. Sylvester who operated a jewelry and "fancy goods" store on Center Street. Though Sylvester most frequently relied upon colorful trade cards with beautiful or humorous scenes on the front and advertising text on the reverse, on occasion he employed novel means to promote his business, including the unique autumn-colored leaves pictured here. Printed on small pieces of serrated paper, the leaves advertised Sylvester's range of gold and silver goods, as well as pictures and frames.

Among the most creative business owners when it came to advertising in late 19th century Middleborough was Solomon H. Sylvester who operated a jewelry and "fancy goods" store on Center Street. Though Sylvester most frequently relied upon colorful trade cards with beautiful or humorous scenes on the front and advertising text on the reverse, on occasion he employed novel means to promote his business, including the unique autumn-colored leaves pictured here. Printed on small pieces of serrated paper, the leaves advertised Sylvester's range of gold and silver goods, as well as pictures and frames. Thursday, October 20, 2011

Pratt Farm Barn

Standing to the left of the entrance of the Pratt Farm on East Main Street are the ruins of a seemingly once formidable structure. A broken concrete pad, a circular foundation and the remains of a large dry-laid stone ramp are the remnants of the former barn built in 1905 which stood upon the site

of the original Pratt Farm barn.

The original Pratt barn was built about the same time as the Pratt House in the late eighteenth century, and it was standing prior to October, 1798, at which time it was described as measuring 30 by 28 feet. This barn was a substantial structure and included a full basement that was utilized as a piggery. In the fall of each year pigs were taken to market, slaughtered and the meat cured for the Pratt family. The basement also likely served as a storage space for manure collected on the farm.

The original Pratt barn was built about the same time as the Pratt House in the late eighteenth century, and it was standing prior to October, 1798, at which time it was described as measuring 30 by 28 feet. This barn was a substantial structure and included a full basement that was utilized as a piggery. In the fall of each year pigs were taken to market, slaughtered and the meat cured for the Pratt family. The basement also likely served as a storage space for manure collected on the farm.

The original Pratt Farm barn stood until 1898 when it was levelled by fire, leaving only the cellar hole. Ernest S. Pratt was thirteen at the time of the barn’s destruction and later in life he recorded his recollection of the event.

…On the 28th of December, 1898, came another disaster. During my vacation week from school, I went with two other teams (I was driving a single horse hitch), carting logs from the area back of the then Shurtleff Place, adjacent to Woods Pond, to Atwood’s Mill at Rock….We had made two trips to the Mill and were returning home by the Chester Weston Homestead on Sachem Street, when the thought came to me, what would I do if fire had destroyed buildings on the Homestead, while I was away. As I came to the gap in the hill, lo and behold, there was an unusual bright light, and fire, in the shed, adjoining the barn, which was used for a slaughter house.

I saw a figure leave the barn and immediately return. The teamsters and I all came to that this was a fire out of control. The others realized the situation and proceeded as fast as possible to help Father save as much as could be taken from the buildings. I conceived the idea that I could be the most service by going at once to the hose house on Star Mill Hill, ringing the fire alarm, and assisting with the horse and wagon to pull the hose reel to the fire hydrant, near the homestead. In my strenuous application of the cart stake to the old horse’s rump, to accelerate speed, I overdid the matter. About where Mr. Judge’s Paint Store now stands, the horse let his heels fly into the air, and came down breaking the shafts and some portions of the harness.

This brought to a conclusion all hopes of me becoming an assistant fireman. I did, however, extricate the horse from the wagon, jumped on his back and rode to ring Box 27, situated then as now, on Mill Hill, in front of the Walker Co. Office. The firemen laboriously pulled by hand the 500 feet of hose, to the hydrant, and laid the line to the fire. Another line was laid by another fire company and the two streams played on the flames. The water main was four inches and the two streams amounted to a good garden hose. It was a bitterly cold and windy night. Firemen suffered frost-bitten hands and fingers. The fire gained such headway that nothing of the building was saved. The water froze into ice all around. The hay smouldered several days and firemen had to wet it down. There was a fire district at this time. Firemen came from all the districts and worked heroically. The flames were visible for many miles. The night was outstanding, and well remembered as “the time that Pratt’s barn burned.” Father had a cranberry house which he used to stable his ten horses. He put the cows in a small shed. The teamsters and my father were able to save the wagons. The cows were turned loose. Two cows suffered frozen udders, and had to be slaughtered. Five pigs were suffocated under the barn.

A much larger barn was erected upon the foundation of the original barn in 1905, and existed until the demolition of the Pratt House sometime in the early 1970s when it, too, was razed. Photographs of the barn reveal a large two-story structure with a pitched roof. During the 1940s, the 1905 barn was enlarged. “[The barn was] done over while I was there,” recalled the late Bob Hopkins who had worked on the farm, “and the roof was cut open and another tier put up in it to haul all your hay up in.”

On the first or ground level floor of the 1905 barn were a harness room, grain room, several box stalls for the horses which were used in connection with the sand and gravel business and for the teaming horses, stalls for oxen, a calving pen and an area for the farm’s cows. The second floor was primarily for the storage of hay that had been harvested on the farm and was accessed from the high ground to the rear of the barn by way of the stone drive ramp. Light-weight wagons could be driven in and also stored during bad winter weather. During the summer months when the wagons were in use, the space was employed to house sleds and pungs which were used to draw wood over snow-covered ground.

On the first or ground level floor of the 1905 barn were a harness room, grain room, several box stalls for the horses which were used in connection with the sand and gravel business and for the teaming horses, stalls for oxen, a calving pen and an area for the farm’s cows. The second floor was primarily for the storage of hay that had been harvested on the farm and was accessed from the high ground to the rear of the barn by way of the stone drive ramp. Light-weight wagons could be driven in and also stored during bad winter weather. During the summer months when the wagons were in use, the space was employed to house sleds and pungs which were used to draw wood over snow-covered ground.

There was a horse-fork installed near the peak of the barn roof which was designed for unloading materials, primarily hay, and was operated by horse power. This was typical equipment on larger farms where tons of hay were handled annually. The fork apparatus consisted of a number of tines suspended from an overhead track that ran the entire length of the barn. Wagons laden with hay would draw up below the open doors of the hay loft and the fork brought forward and released by a hand-line to a man on the load who would grasp the tines and sink them into the hay as far as possible. On command, the horse then pulled a large portion of the load up to the overhead track and along into the barn where it was released by means of a trip-rope, thereby depositing winter feed for the cattle in the hay mow.

The barn also included a silo for green silage. Jim Maddigan recalled local corn harvests during the late 1920s and early 1930s in the neighborhood of the Pratt Farm:

When the field corn was ready for harvest …the young men cut the corn and tied it into bundles ready for transport to the cow barns for green feed. Some of the farmers had corn silos where the fresh corn was fed through a machine that cut it into small pieces and blew it into the silo. Again [the job of the boys and younger men] was to spread it evenly around inside the silo and pack it down.

The barn was also used to stable the numerous horses that the Pratts owned over the years which were employed in the agricultural, contracting and ice businesses operated by the family. L. Brad Pratt owned many horses - the Pratt Farm barn was described in 1898 as being “full of horses” – and he “used to race with the other sleighs and fast horses” when snow was well packed on North and South Main Streets. Pratt taught his three children – Ernest, Louise and Isabel – each to drive a horse at an early age. Many of the Pratt family horses were buried by Brad Pratt atop the flat hilltop field near the junction of the Farm and Stony Brook Roads.

During the 1930s, the Ernest S. Pratt owned as many as five saddle horses, but as time gave way to automobiles the number declined and by the 1940s just three horses remained, draft horses Jerry and Ned, and a riding horse named Teddy. Bob Hopkins who was employed on the farm during the early 1940s remembered Teddy, acquired by Ernest Pratt during the 1940s gasoline shortage from the Taylor Farm on Vernon Street in North Middleborough.

"We had two draft horses and then the riding horse [Teddy]…. That riding horse broke more … wagons than you can shake a stick at. The first day we hooked him to the wagon he broke the shaft. You’d get him in there and he’d get excited.” Both Hopkins and his brother-in-law Paul Carter who was engaged as Pratt’s herdsman would ride Teddy despite the horse's temperamental disposition. “That horse had a mind of its own…. Some days you’d go out with him and he’d give you a beautiful ride, just smooth, he’d go along beautiful and another day you don’t know whether you’re going to come back or not because he’d lead you off somewheres…."

"We had two draft horses and then the riding horse [Teddy]…. That riding horse broke more … wagons than you can shake a stick at. The first day we hooked him to the wagon he broke the shaft. You’d get him in there and he’d get excited.” Both Hopkins and his brother-in-law Paul Carter who was engaged as Pratt’s herdsman would ride Teddy despite the horse's temperamental disposition. “That horse had a mind of its own…. Some days you’d go out with him and he’d give you a beautiful ride, just smooth, he’d go along beautiful and another day you don’t know whether you’re going to come back or not because he’d lead you off somewheres…."

Hopkins recalled being able to drive horses along the Farm Road straight through to Chestnut Street, including the strong-willed Teddy. “You could drive horses right through there. [One day though], I went straight but he didn’t. I didn’t get through and I didn’t get hurt or anything, I just got my feelings hurt because I had to walk back.” Teddy’s headstrong ways, however, sometimes had amusing consequences including for one of Pratt’s employees who felt that he would be able to handle the horse better than either Hopkins or Carter. Hopkins recalled the employee as one who “will show you how to do everything. He knows everything. He knows how to ride. He knows all of this. He’d talk to my brother-in-law and I about it and we’d look at each other, winking our eyes. He’d get on that horse and show us how to ride him. Paul says to him, “You want me to harness him up for you?” “I’ll show you how to ride him, you harness him up.” So we harness him up and we knew what was going to happen…. As I say, like with me the horse goes curve and I go straight.” The rider resulted with a hurt leg and a bruised ego. “He had to walk all the way back…. Here comes the horse sauntering down there like he owns the … place, up to the barn. A little while later … comes [the rider]. He didn’t say anything when he came back. We weren’t that dumb. I don’t care how smart you were, [Teddy] was a very smart horse.”

Rose Standish Pratt in 1967 recalled another of the Pratt Company’s horses also named “Teddy” who had the misfortune of falling through the ice pond four times during one particularly brutal ice harvest earlier in the century. “Each time he was pulled ashore, dried off, and harnessed again…. After four efforts the iceman decided the ice would have to be thicker before it could be worked on.” Also remembered by Louise Pratt was “Little Dandy”, one of the family horses which drew the democrat wagon or the trap, on family outings on Sunday afternoons. “We drove to nearby towns or countrysides, sometimes to visit, once to Pope’s Point to see a harness maker. I remember a day’s trip to see relatives in Sagamore over dirt roads in a carryall and with a pair of horses.”

The selection of heavy harness horses to draw the Ernest S. Pratt Company's ice wagons in summer was careful. “They must be patient, although ready to move at the sound of the driver’s voice to save time,” explained Pratt’s wife Rose.

The selection of heavy harness horses to draw the Ernest S. Pratt Company's ice wagons in summer was careful. “They must be patient, although ready to move at the sound of the driver’s voice to save time,” explained Pratt’s wife Rose.

Besides horses, the Pratts over the years also owned oxen. Simeon M. Pratt owned a team of oxen which he undoubtedly used for heavy hauling and probably plowing. Later, Brad Pratt seems not to have owned any of the powerful beasts but occasionally engaged George Robbins or his son, Carroll, who lived on a farm on Wood Street which backed up to the Pratt Farm , for carting sand or gravel with their ox team.

Behind the barn are two poured concrete walls - an outdoor bull pen located just southeast of the barn near the base of the bridge to the second floor. The bull was an important feature of the farm, particularly when Ernest Pratt pursued the breeding of Guernsey cattle. The barn also included an earlier bull pen.

At one time there was a also shed located adjacent to the barn and utilized as a slaughterhouse in the late nineteenth century. This was undoubtedly connected to the meat business operated by L. Bradford Pratt for twelve years. It was in this building that the 1898 fire which destroyed the original Pratt barn started. This building was lost at the time, as well. Following the incident, L. Brad Pratt sold his meat business at the start of 1899 to the meat market which operated on Wareham Street at Middleborough center.

Behind the barn was a strawberry field where the children of L. Bradford Pratt picked the berries, selling the extras “for fifteen cents a box or two for a quarter.”

llustrations:

Ernest S. Pratt Company Ice Wagon, Pratt Farm, Middleborough, MA, photograph, early 20th century.

The matched pair of horses and ice wagon stands in front of the 1905 barn on the Pratt Farm, a portion of which can be glimpsed behind the team. The barn was used to stable the numerous horses used by Pratt in his ice business and whose work involved both harvesting the ice and winter and delivering it in summer.

Pratt Farm Barn, Pratt Farm, Middleborough, MA, plan byMike Maddigan.

The plan shows the general layout of the barn constructed in 1905 on the Pratt farm as described by Paul Carter, the Pratt Farm herdsman, to James F. Maddigan.

Bob Hopkins and Teddy, Pratt Farm, Middleborough, MA, photograph, early 1940s.

Hopkins who worked as an employee of Ernest S. Pratt for a period of time in the 1940s is pictured with Teddy, one of the last saddle horses owned by Pratt. In the distance are the original ice houses which stood on the Pratt until blown down during the hurricane of September, 1944.

Ernest S. Pratt, Pratt Farm, Middleborough, MA, photograph, early 20th century.

Pratt was photographed by his wife, Rose Standish Pratt, with two of his ice horses. The sturdiness of the animals which drew Pratt's ice wagons and performed numerous other tasks about the farm is obvious.

of the original Pratt Farm barn.

The original Pratt barn was built about the same time as the Pratt House in the late eighteenth century, and it was standing prior to October, 1798, at which time it was described as measuring 30 by 28 feet. This barn was a substantial structure and included a full basement that was utilized as a piggery. In the fall of each year pigs were taken to market, slaughtered and the meat cured for the Pratt family. The basement also likely served as a storage space for manure collected on the farm.